Denver's streets were a mess. Cars bumped down icy, rutted roads. Citizens clamored for better plowing. City hall defended itself, saying its workers were doing their best.

Yep, this happened after the sloppy snowstorm that hit Denver late last year (and perhaps it will again after this week's dump). But a review of local newspaper archives shows it also happened in 2019, 2003, 1987, 1982, 1979, 1973, 1946, and almost certainly more years before and in between.

To be sure, complaining about snowy, icy streets is a time-honored tradition for taxpayers most everywhere flakes fall. But Denver's combination of climate, built environment, abundance of cars, and desire among city leaders and taxpayers to keep costs down have long made it susceptible to occasional megastorms that overwhelm city resources and outrage its motorized citizenry.

The basics are this: Denver's urban core receives an average of about 60 inches of snow annually, with most storms in the trace to 3-inch range. Big snowstorms are relatively rare, and sunny, warm days are common throughout the winter. So the city's snow removal system has historically not been as muscular or costly as those in snow-belt cities with grayer skies.

"The additional melting of snow reduces the cost of emergency snow response in comparison with other cities that experience similar snowfall amount but have different climate conditions," the city's current snow plow plan states.

Denver and other U.S. cities that see only occasional snow take a low-impact approach that's easier on the environment, causes fewer headaches for car-owners who rely on street parking and want to avoid rusty fenders, and, of course, costs less money for taxpayers.

"Often the best strategy is you wait two days and hopefully it'll be 50 degrees. Much of your problem melts," said James Campbell, professor of supply chain and analytics at the University of Missouri in St. Louis. "That works sometimes in a place like Denver -- but sometimes it doesn't."

Denver's sometimes-it-works, sometimes-it-doesn't approach has been in use for a long time.

It's been around at least since the days of Benjamin Stapleton, who was mayor of Denver from the 1920s to the 1940s (with a brief break in the 1930s). And city officials learned back then that it's a policy that cuts both ways.

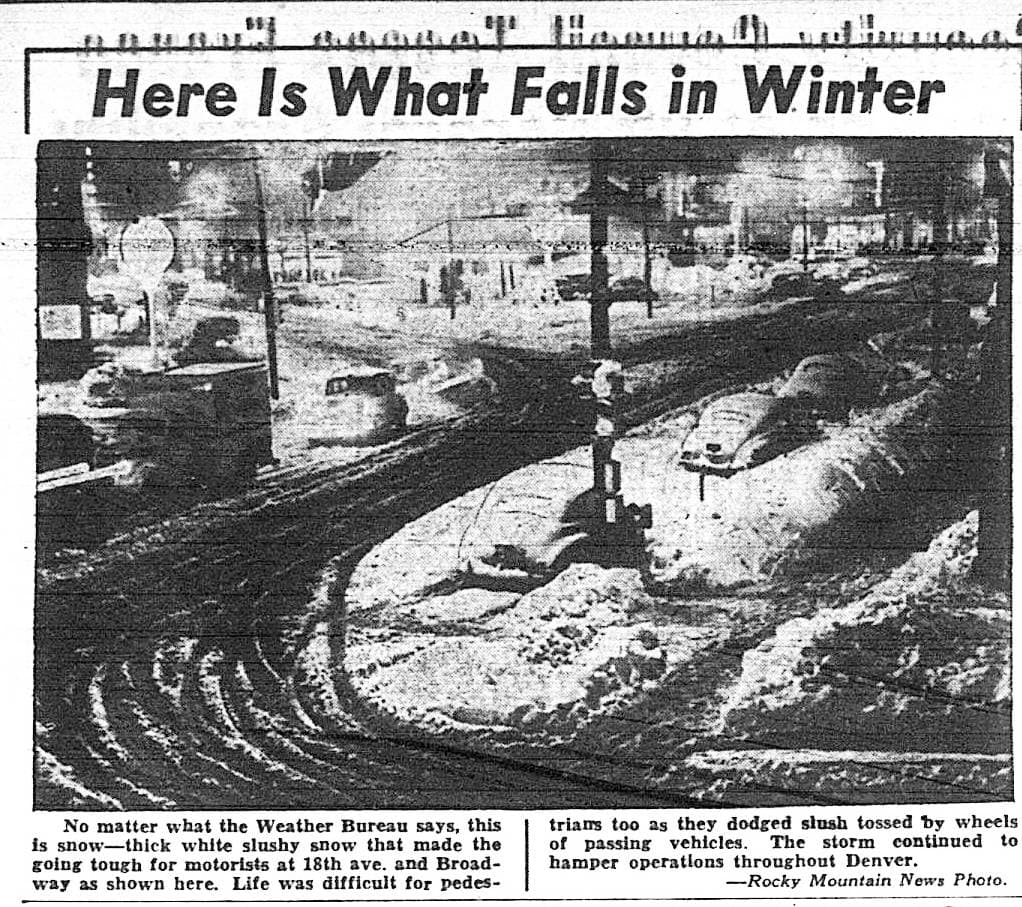

More than 30 inches of snow fell in the city in early November 1946, the heaviest in three decades. Streetcars, buses and automobiles were paralyzed for days. Nearly 500 city employees worked to clear downtown streets, pulling shifts of up to 24 hours straight.

But streets elsewhere in the city weren't touched for days, The Denver Post editorial board complained nearly a week after the storm ended.

"One fact stands out: Denver had no plan," the editorial board railed. "Mobile, Ala., could be expected to find a heavy snowstorm disturbing and disrupting. Denver ought to be able to take a storm in its stride."

Then, temperatures plummeted as another storm arrived. The snow was packed into ruts on city streets that lasted for nearly two weeks. The Post reported that the city's limited mechanical snow-shoveling equipment was "hopelessly inadequate."

The basic facts of the 1946 storm have reappeared again and again over Denver's history. Here's what we learned from reviewing archival news stories from that and other storms over the decades -- and a handful of new interviews.

Yes, Denver has traditionally relied on the sun to help clear streets.

About two weeks after the 1946 storm, sustained warm weather finally arrived. Melting ice exposed heavily damaged roads, which city officials tried to downplay.

"I am confident that the city's streets will not be too long in returning to good shape," Parks Manager George Cranmer told the Rocky Mountain News. "We are hoping for a mild spell during which they can dry thoroughly."

The Denver Post's editorial board was not buying it. In another editorial, entitled "Didn't Wait for the Sun," the Post lauded the state highway department for its rapid plowing of state roads while slamming the city for relying on the sun to clear arterial streets.

"Now that the ice is melting and what is left of our tires is dropping out of sight in the pits eroded in the surfacing, we suppose George will reassure us with, 'the condition of Denver's streets is 'holey' satisfactory,'" the editorial read.

But the city continued to rely on sunshine. "Denver's policy is to clear the worst snow from major streets, sand heavily to give drivers better traction and hope for its climate to do the rest," the Denver Post wrote in 1985.

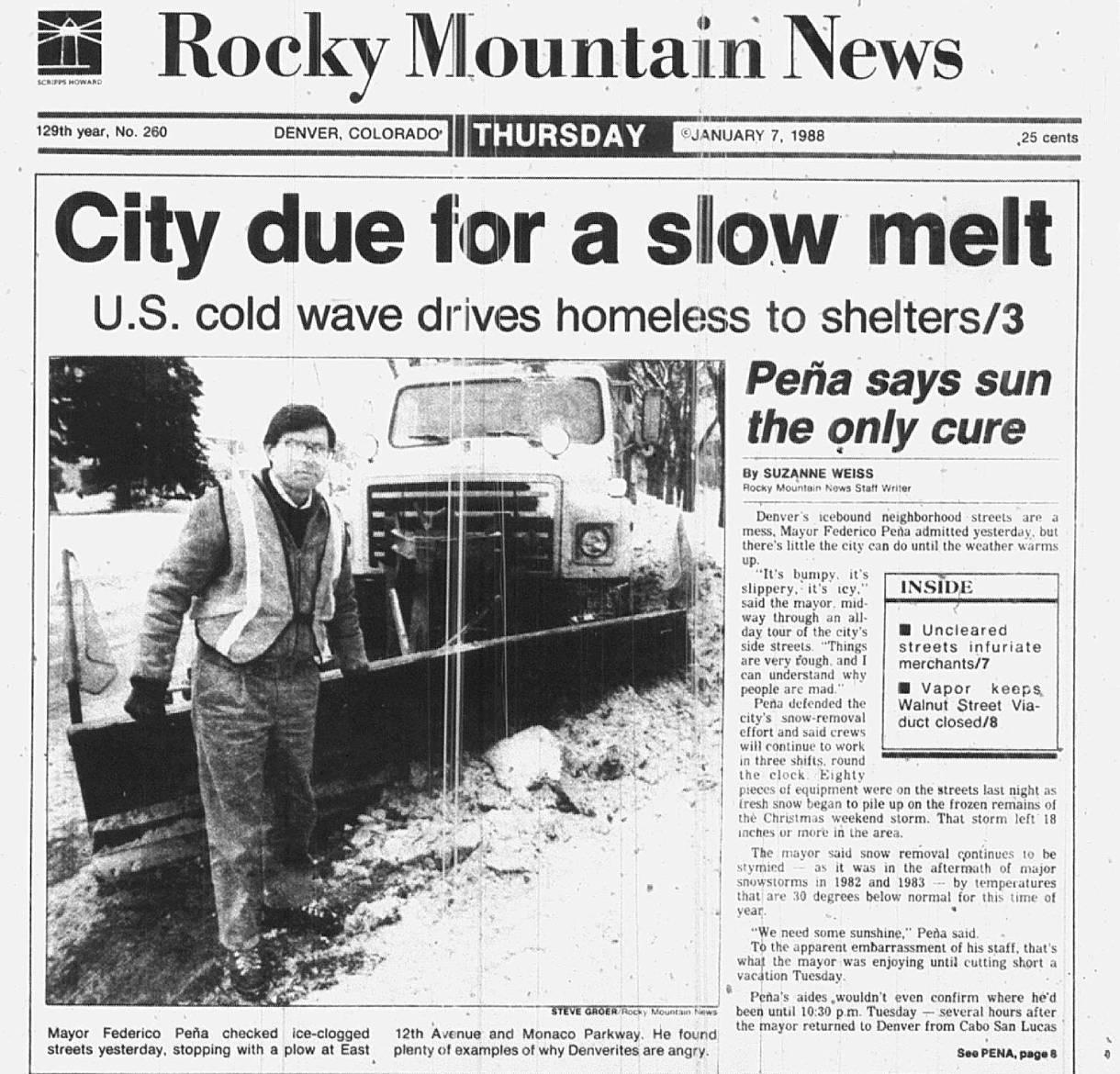

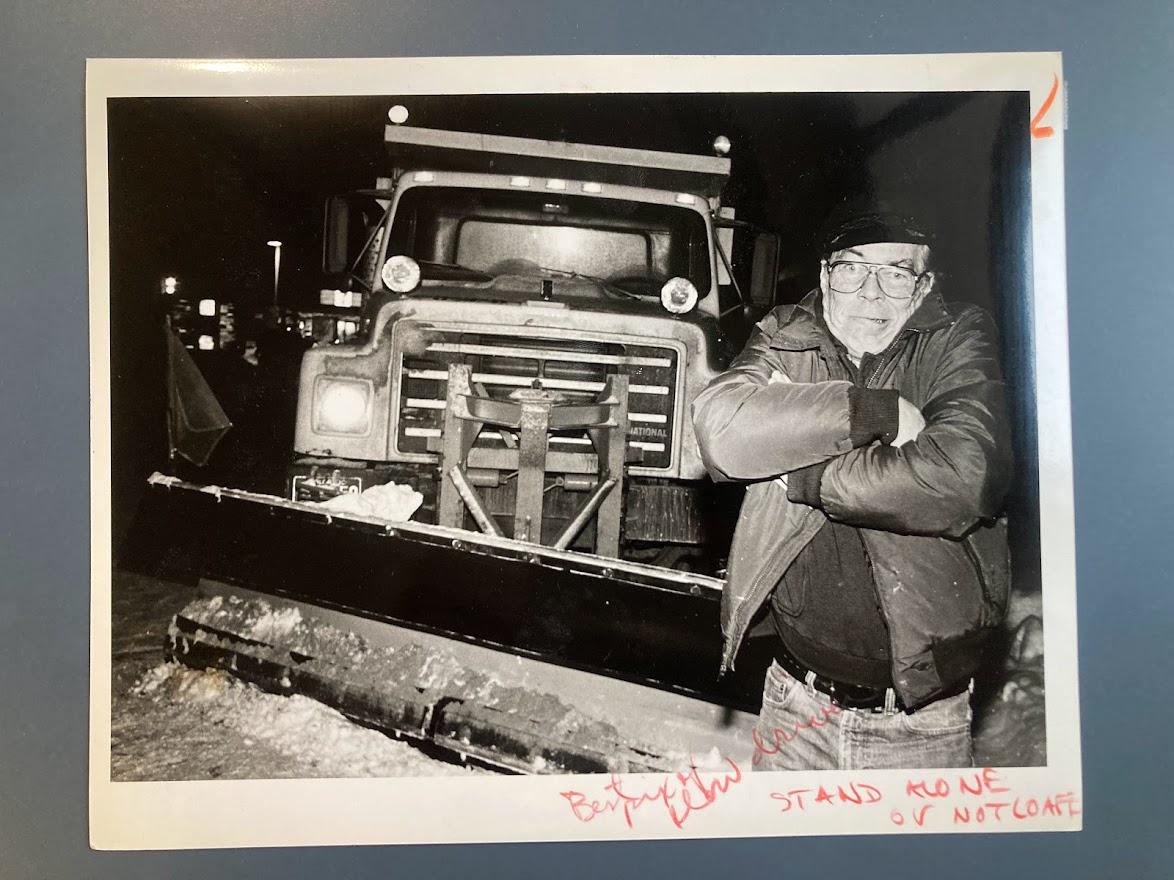

After a particularly nasty storm in late 1987, then-mayor Federico Peña was facing outrage over rutted streets while he was on vacation in Mexico. He returned early from his trip and said there was little the city could do until the weather warmed.

"We need some sunshine," Peña told the Rocky Mountain News then. He declined Denverite's request for an interview last week.

Denver still embraces the sun, said Denver Department of Transportation and Infrastructure spokeswoman Nancy Kuhn.

"That's the benefit of Denver compared to a lot of other cities," she said. "The sun does come out, the streets rebound pretty well, and we're grateful for it."

Denver has long tried to limit its snow removal budget.

As The Denver Post was slamming the city's plowing after the crippling 1946 storm, it was also advising city leaders to make cuts to its overall municipal budget. Then-Mayor Benjamin Stapleton had been pushing for a tax increase to pay for climbing city expenses and salaries, to which the Post commented: "One thing certain, the people of Denver don't want anymore taxes."

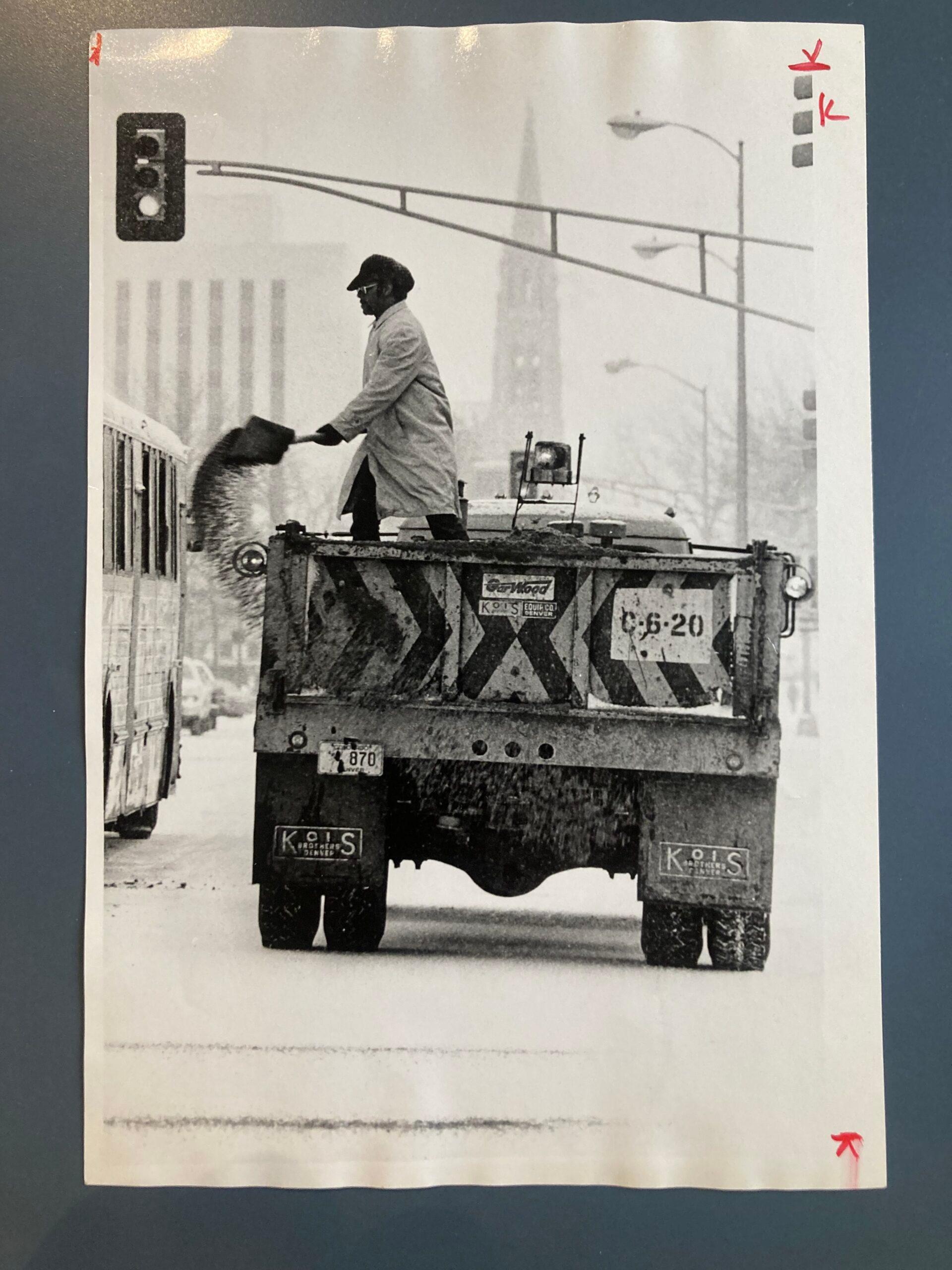

City leaders kept a lid on snow removal spending for decades after that. Denver had just two plows available in 1973 when a storm paralyzed the city, which did prompt the buying of some new equipment.

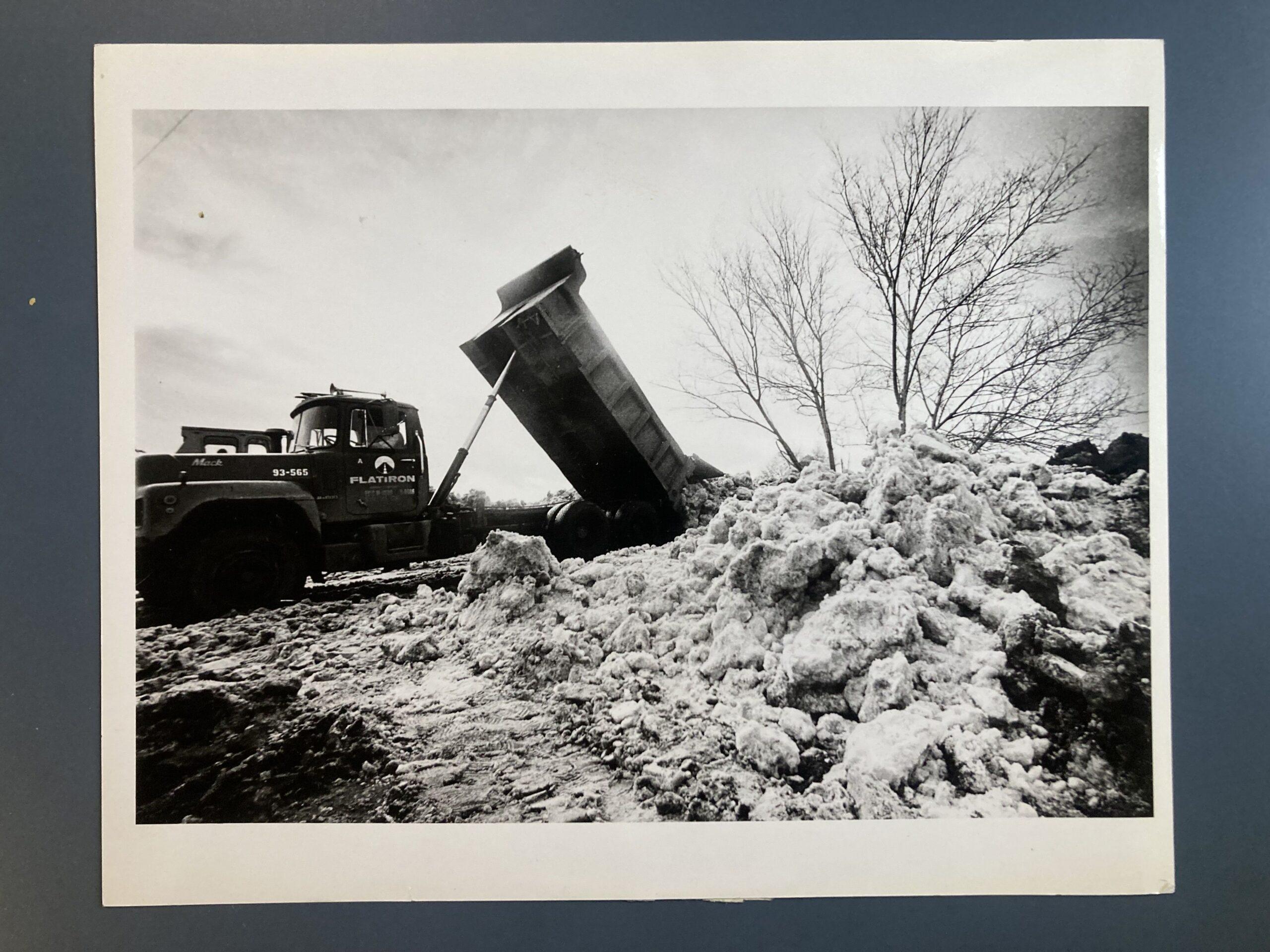

Finally, the notorious Christmas Eve blizzard of 1982 put Denver's tight-fisted approach to the test -- and it failed miserably. Nearly 2 feet of snow fell, and plowing crews were slow to respond. City officials defended themselves, citing the budget-minded snow removal policy they said dated back to the Stapleton days.

"We can't afford to buy and keep idle the amount and kind of equipment it takes to quickly handle the kind of heavy storm that comes along only every 10 years or so," Harold Cook, Denver's deputy mayor and snow removal czar, told the Post in January 1983.

Mayor William McNichols, Jr. told the paper it would be "stupid for any city to waste tax money like that."

But Denver ended up spending $7.6 million to clear the snow from that one storm -- an eye-popping sum for the time. The fiasco contributed to voters turning on the long-time mayor, newspapers reported at the time, who was voted out of office that year.

"We're totally disgusted with the whole snow-removal situation," one Capitol Hill resident told the Post.

City spending on snow removal did increase in the 1980s -- from just $625,000 in 1981 to $2.18 million by 1985, the Post reported.

But it's unclear exactly what that spending encompassed, so it's difficult to compare those historical numbers to current spending. The city didn't provide Denverite with numbers detailing its long-term snow-removal spending by the time this story was published.

City spokeswoman Kuhn said Denver spends about $3 million on snow removal materials, plus more on staffing and vehicles. Total operating costs can range from $12 million to $25 million annually, she said, depending on how severe storms are in a given year.

Kuhn added that the city aims to remove snow in an "efficient, effective, and fiscally responsible manner."

The recurring public outrage over bumpy streets indicates there may be an appetite for increased spending on snow removal -- and some candidates in this year's mayoral election say they'd push for it or at least are open to it.

But Stephanie Foote, a former City Councilor and head of the city's public works department during a megastorm in March 2003, said it's just not fiscally responsible to budget for the worst possible storm.

"You'd have all that staffing, all those people, all the vehicles and everything all sitting there with really nothing to do," she said, echoing her predecessors. "That's not a smart use of money."

Why not plow more streets to the curb? Denver's tried it.

After the Christmas Eve 1982 megastorm, Denver designated "snow routes" where on-street parking wouldn't be allowed when the city declared a "snow emergency." Such parking restrictions are common in snow-belt cities like Minneapolis, where residents must move their cars so plows can better clear streets to the curb.

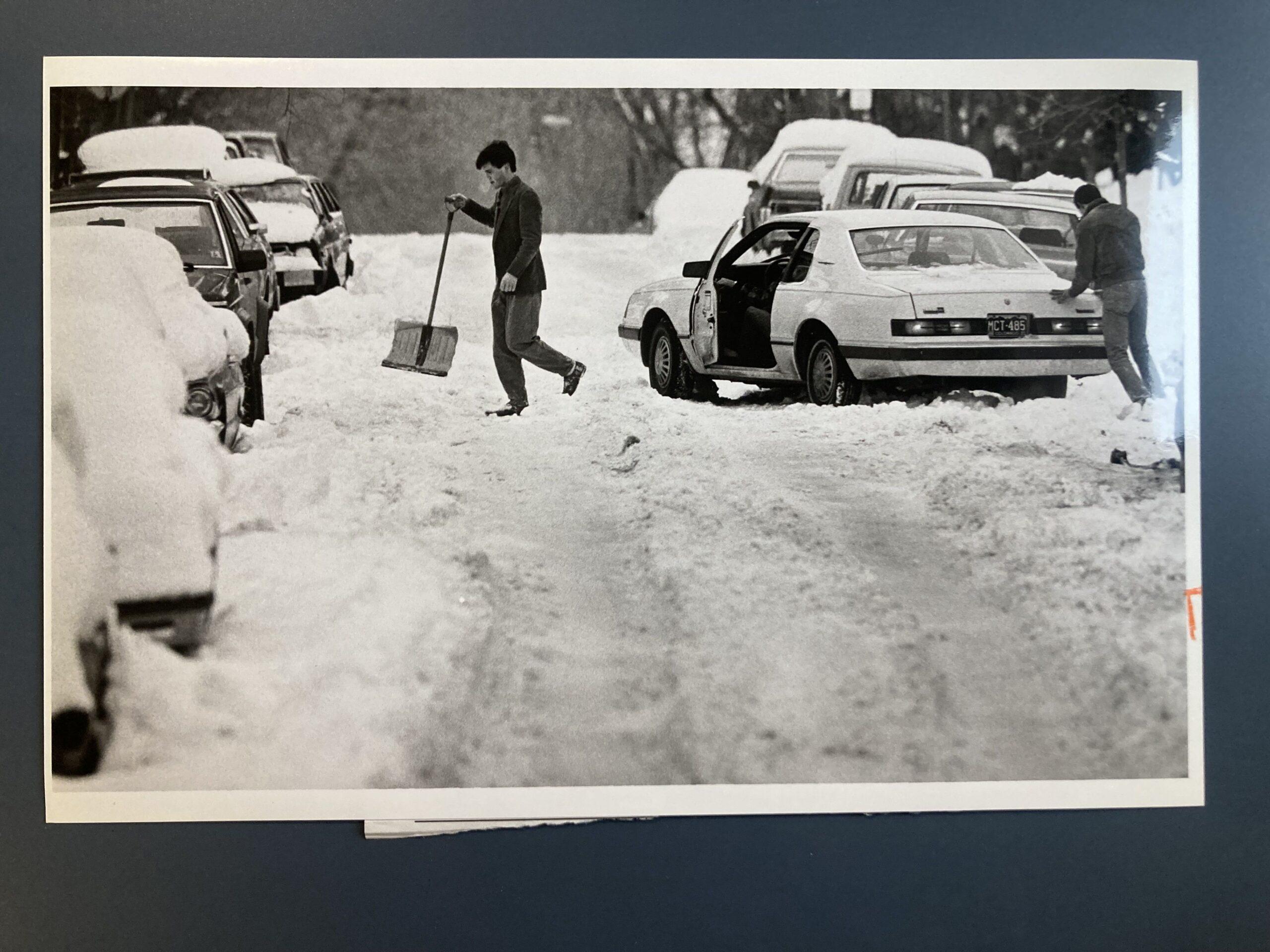

The parking rules proved difficult to enforce. During a big November 1983 storm, Peña officials didn't declare an emergency until 17 inches of snow had fallen and cars that needed to move were already buried. City officials also didn't enforce the rules consistently -- cars were towed from some snow routes but not others.

"What good does it do to pass the ordinance if you don't enforce it?" one city councilor asked Peña officials after the storm.

There was another problem, too: In relatively dense neighborhoods like Capitol Hill and Washington Park, one city councilor said at the time, residents that had to move their cars were "having a terrible time trying to find a place to park."

The snow parking program was soon redrawn to concentrate on main roadways in and near downtown. It was enforced inconsistently through the years and further trimmed under Mayor John Hickenlooper in 2007.

Any effort to bring back parking restrictions would be a big adjustment and would require community discussion, said city spokeswoman Kuhn.

"If that becomes a priority, then I think that's something we could discuss," she said.

Currently, Kuhn said, Denver plows get close to the curb on major streets where parking isn't allowed. Elsewhere, plows push snow up against cars left on the street.

"If you have an opportunity to do so, move off the street," she advised.

Why not toss down more salt and sand? Denver's tried that, too.

In 1986, the city announced it would amp up the amount of salt it used on certain hilly roads and overpasses to match concentrations used in Detroit, Cleveland, Chicago and other northern cities.

The pushback was immediate. Car dealerships and residents worried the extra salt would rust vehicles and destroy plants. Complaints poured into city offices. Peña and his deputies initially defended the plan but backed down less than a month after announcing it.

"It's probably the most response we've had to any single issue during this administration," Pena's public works manager said at the time. "We're willing to try things. If we try and it turns out that it's not something the public accepts, we'll retreat."

In the 1990s, Denver tamped down on the amount of traction-enabling sand it spread on streets because it eventually was kicked into the air and helped contribute to the city's "brown cloud."

Now, Denver uses liquid magnesium chloride to pre-treat roads and aid melting on downtown streets. Elsewhere, it uses a dry de-icer that's more environmentally friendly than traditional salt and sand. But the city still limits its use and sweeps it up after storms in the name of air and water quality.

"We don't skimp on de-icer," Kuhn said. "We use it for safety and we use it judiciously."

One more weird historical detour: In 1983, Denver floated and then quickly abandoned "Operation Trash Mash," which would have sent heavy trash trucks down side streets to pack down the snow.

If Denver won't spend more money on plows, and we can't use more dry de-icer, what's left for a frustrated driver to do?

There is one thing Denverites can do, said Campbell, the University of Missouri professor. People in cold-climate cities like Montreal have a more positive and constructive culture around snow removal, he said. They complain less about the presence of snow and are better at moving their cars to let plows work. Residents of cities like Denver could learn from that, he said.

"The citizens are maybe not as helpful as they could be in terms of getting out of the way, really, of the professionals," he said.

Special thanks to the research librarians at the Denver Public Library.