It was 2017, and Kaylee Browning was struggling to hear.

Browning was working as an aide for Democratic State Representative Leslie Herod, who is running for mayor of Denver. Browning said she had tumors near her ear that made it difficult to hear what Herod was saying in their cavernous office in the Capitol.

At one point Herod was, "like 'why can't you hear me?'" said Browning, who felt it was mocking. "Kind of like the head nod attitude about it. And it was something I couldn't get a hold of."

Browning said several months earlier she had taken leave from Herod's campaign to have surgery for the issue.

Despite the surgery, Browning still had difficulty hearing. She lost her health insurance when she went to work at the Capitol, and couldn't afford hearing aids until after the session.

She described her work with Herod as less policy and politics and more waiting on Herod. Aides were constantly getting food and coffee and flowers, fronting the costs at times. Occasionally they didn't get paid back for days or weeks.

Other former aides are divided on how Herod managed them. Some say they, too, were asked to wait on her or go beyond their listed job description. Others say Herod was a tough boss that got things done and demanded more of her staff.

Herod is seeking one of the most powerful political jobs in Colorado, mayor of Denver, a position with vast control over the 13,000-person workforce, the budget and cabinet appointments. Finding competent staff and supporting and engaging them is critical to the functioning of the city.

"It was rough. It was really rough," Browning said. "She was very mean. I don't remember like yelling so much, it's like 'you have poor critical thinking skills,' like degrading to the point of like you just could not do right by this individual."

Throughout the 2017 session, Browning said Herod alienated her small staff, and on the last day they didn't celebrate together, like other lawmakers and aides.

Dejected by the experience, Browning left politics for good on the last day of that session.

Denverite spoke to a dozen other aides and lawmakers, all of whom spoke on condition of anonymity, for fear of reprisals.

Many didn't want specific incidents published because it would identify who said it.

In an interview with Denverite, Herod said the allegations of mocking Browning's hearing disability are baseless.

"I would never, and have never, mocked anyone for any type of disability," Herod said. "In fact, my mom was a host home for people living with developmental disabilities through my high school life. We've always been open and accepting as a family when it comes to, not only acknowledging and seeing people with disabilities, but fighting for them."

Since coming to the Capitol in 2017, Herod has established herself as a legislative force, passing numerous bills, including landmark reforms in policing and drug policy, and serving as a member of the powerful Joint Budget Committee that writes the state's budget. She has long been a rising star in the Democratic party.

Herod is a gay Black woman with power, on the cutting edge of progressive policy in Colorado. And many of her allies say that makes her a convenient target of criticism. In 2021, the Weld County Sheriff called her a 'terrorist,' to a group opposing COVID mandates. And Herod was worried about her personal safety.

Herod told Denverite she was taken aback to hear of the negative experience staffers had.

"This is the first time I've ever heard of it," she said. "I have never received any complaint at all from any of my aides or staffers."

On getting food and coffee, Herod said she had to do that when she was an aide. "Part of the job is making sure that we get through those long hours," Herod said. "I know folks sometimes think this job is different than what it was. And as a freshman legislator [in 2017], I could have done a better job prepping on that."

Other staffers, especially in more recent sessions, said they had positive experiences.

Herod's campaign provided contacts to Denverite for about a dozen lawmakers and former and current staff. Some staffers ultimately didn't want to speak on the record, but two former staffers did.

As to the allegations of mocking someone who couldn't hear: "That doesn't sound like the Leslie I know," Sophie Hackett, a former Herod aide in 2020, said. "I'm not gonna speak to anybody else's experience, but that was not mine.

"She was a great mentor to me. She was tough, but we got stuff done and really elevated the way that I work."

All the aides who worked with Herod, who spoke with Denverite agreed she is a tough boss, and some people can handle that, others have a difficult time.

"Honestly, that doesn't surprise me," Phoebe Blessing, a former aide, and now the policy director for Herod's mayoral campaign, said. "Leslie is a very demanding person to work for. She does everything. Having been in charge of her calendar, I can tell you that she's everywhere. And she's doing a lot of things, and she expects and demands really high work from the people who work for."

Blessing said, though, that Herod is also kind and thoughtful. When it came to getting food and coffee, Herod was up front with Blessing that that was part of the job.

Blessing said criticism she heard of Herod at the Capitol was always from people who hadn't actually worked for Herod.

"Working with people who had worked with her for longer than I had, I didn't hear any of that from them. It was all outside. External," she said.

One lawmaker, who Herod referred to Denverite, State Rep. David Ortiz, said part of the problem is the Capitol has become overly sensitive, especially compared to his time in the military.

"In politics you really have to, I think to the detriment of the work, you really have to focus on people's feelings and how things can be received, instead of focusing on the policy itself sometimes," he said.

But Herod, Ortiz said, was an excellent lawmaker, who brought diverse stakeholders together, and formed close relationships with other lawmakers.

"Have I heard that Leslie can be tough on her staff? I mean, I've heard those rumors too," said Ortiz. "I've never witnessed it. That being said, I've never been close to any of her staff."

Browning, however, said her experience working for Herod was traumatic.

She was, at first, impressed by Herod.

"It was really exciting, because we were representing her, and there was all this promise behind her," Browning said. Herod was the first openly gay Black woman elected to the Colorado State House. A bright spot in 2016 for the Democratic party after Donald Trump surprisingly won the presidency.

Browning said she started working for Herod on her first campaign for the state house, in October 2016. When Herod won, Browning went to work as an aide for Herod at the Capitol, starting in January 2017.

But Browning's dream of being involved in politics or policy in Herod's office quickly soured, she said.

"It was a lot of running around and getting her three meals a day, making sure she has a burrito in the morning, setting her bills out in the perfect structure, making sure she had fresh flowers, fresh water. Every day fresh flowers," Browning said. "And so it was like this ongoing act of like waiting on her hand and foot. That was when I decided like, I can't do politics. Like if this is what is celebrated, I'll never be able to make it here."

Herod said she never had staff get her food or flowers daily.

"I quite frankly wouldn't be able to afford that," she said. "But there is coffee in the building and there are times when we're not allowed to leave. ... we're in votes, we need coffee. Sometimes we're there until 2:00 AM. Last year we were on the floor for 25 hours. No matter your title, your role, I've gotten food for members. Yeah, you have to do that."

On one occasion, Browning said Herod asked her to get her a skinny vanilla latte from City O' City, a coffee shop a block from the Capitol.

"She liked almond milk and apparently the almond milk can burn, and so that happened," Browning said. "And so she would like throw it away and like, 'get me another one.' I remember that I burned out my heels from just rushing back and forth between City O' City."

Herod said that never happened: "That's not factual," Herod said.

Browning never filed a complaint, but the general outline of her account was corroborated by other Capitol staffers who knew her, and by friends and family she confided in at the time.

Getting food and coffee may be a common part of the job, but that's nowhere to be found in a 2020 job description for a legislative aide for Herod.

Though aides from more recent sessions, said Herod is clear upfront that getting food and coffee is a necessary part of the job.

It is not uncommon for an aide to run the occasional errand for a legislator, for food or coffee.

Aides don't make a lot of money, and the job can be difficult in a high pressure environment. But the experience of being involved in state policy was so valuable that Browning said she stuck it out for the session to get the experience.

Still, Browning hit a breaking point.

"It was constantly being in servitude, and not in a healthy or positive or even in a way that would put me in a position to then use that experience later in my career," she said.

Browning said she and other aides were expected to front the cost for food and coffee purchases, and they wouldn't get paid back by Herod for sometimes weeks.

In 2017, Browning said she made $12 an hour from the state and was paid an additional $5 an hour from Herod's campaign account. Herod would regularly tell Browning that she was the highest paid aide in the Capitol.

Herod would drive aides to tears on such a regular basis that it caught the attention of staffers for other lawmakers who sat near Herod on the House floor, according to several aides.

"We were always getting looks, it was like we were the battered children in the building and people would look at us sadly," Browning said.

Herod said the jobs of lawmaker and aide are tough, and Herod said she cried at times, too.

Herod said she often can spot when an aide is overworked or under a lot of pressure. "I would reach out to them and say, 'Hey, are you okay? Do you need time off? You know, do you need a day?'"

But several former legislative staffers said in 2017, Herod's aides would hide in other lawmaker's offices to avoid her.

"That's a surprise to me," Herod said. "Because I think most of my staffers would say, I'm rarely in the office because I was always on the floor running bills."

Several aides in the Capitol said this treatment of aides, by Herod and other lawmakers, helped propel unionization efforts.

"In our work representing legislative aides and other political workers," reads a statement from the Political Workers Guild of Colorado to Denverite. "It has been our experience that many politicians who advocate for progressive values fail to practice said values in their own offices or on their own campaigns.

"Unfortunately, these stories of unacceptable mistreatment are neither news nor a surprise to us. Many of our members have had positive experiences in the legislature as aides, but many more have faced the systemic and individualized bullying and lack of respect that those in power believe they can perpetrate without fear of discovery or consequence. We are proud to stand with the staffers who are speaking up about these issues, and are committed to continue improving the working conditions of aides who still experience the fear of retaliation that makes it dangerous for them to speak publicly as well."

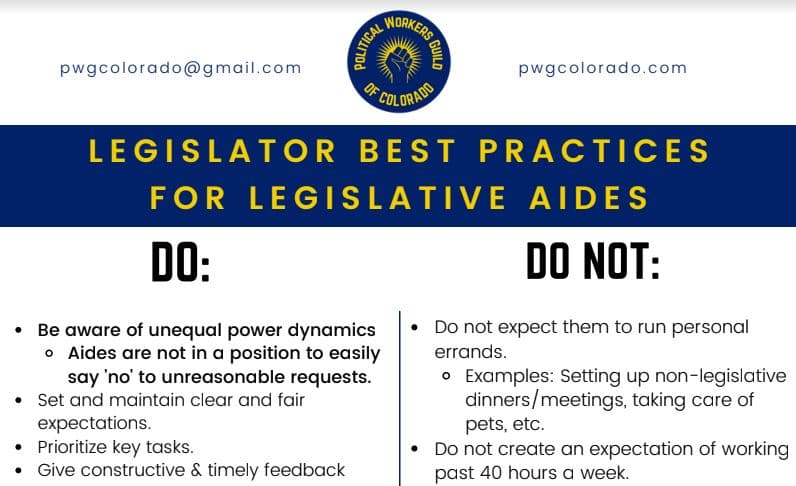

One aide active in the union said this kind of treatment of staff helped inspire a best practices list that the union has put on every lawmaker's desk at the start of the session the last two years.

Source: Political Workers Guild of Colorado

Once, during the 2017 session, Browning said Herod confronted her over a discrepancy in Browning's timesheet. Basically, "it looked like I had lied about my hours, and instead of asking me or trusting me, she immediately became accusatory."

It turned out to be a clerical error by another legislative staffer, and it was easily corrected, Browning said.

But it left her so afraid to speak to Herod about her hours, that later Browning didn't cash a $1,000 paycheck she received at the end of the session. "I was under the impression that I was overpaid, and I was so scared that I didn't take the money. So if anyone does an audit and gets me my thousand bucks, that'd be great," she said with a chuckle.

Browning has not donated to any Denver mayoral candidates, and has not worked on any campaigns. She said she left politics altogether after the 2017 session, got her PhD, and is now a lecturer.

Despite her negative experience, Browning said she strongly supports the progressive causes that Herod has championed at the legislature, and she even gave $200 in contributions to Herod's leadership fund between 2020 and 2021.

But she was inspired to tell her story, because she's heard over the years that many of Herod's aides have had similar experiences. And seeing how close Herod is to potentially becoming mayor of Denver brought feelings back to the surface.

"Those feelings of worthlessness, and what brings me here today is the anger that I feel and the sadness," Browning said. "That she would do this to other people and that would continue on. And that's not acceptable to me. And that is the only reason I'm speaking out. And I'm so frustrated to even be in this position, but it's like she already ran me out of politics."