Ernie Madril worked all his life, mostly hard labor, until he couldn't. He's a Coloradan, born and raised in Leadville, where his career started in a mineshaft.

"I worked at the Eisenhower Tunnel up there, I helped do that. I was a lot younger then, though," he told us from a friend's apartment off Leetsdale Drive, where he's been sleeping in a bed in the living room. "And then my legs got blood clots, and I couldn't work no more."

While he was in the hospital, he said, he gave his rent money to a friend. Instead of paying the bill, his former buddy took off with the cash, leaving Madril broke with nowhere to go.

"That's how I got evicted," the 68-year-old told us. "Being homeless is new to me. I didn't know what to do."

Madril said he bounced between friends' and family's couches, but he worried he'd wear out his welcome. Then, someone pointed him to a case worker with Catholic Charities, who connected him with the Colorado Village Collaborative's (CVC's) Safe Outdoor Space (SOS) program - sanctioned campsites that opened during the pandemic.

The former miner was grateful for a safe place to land. It took time, but eight months later, a case manager working in the camp managed to get him a voucher and his own place. Not everyone in the camps makes it that far.

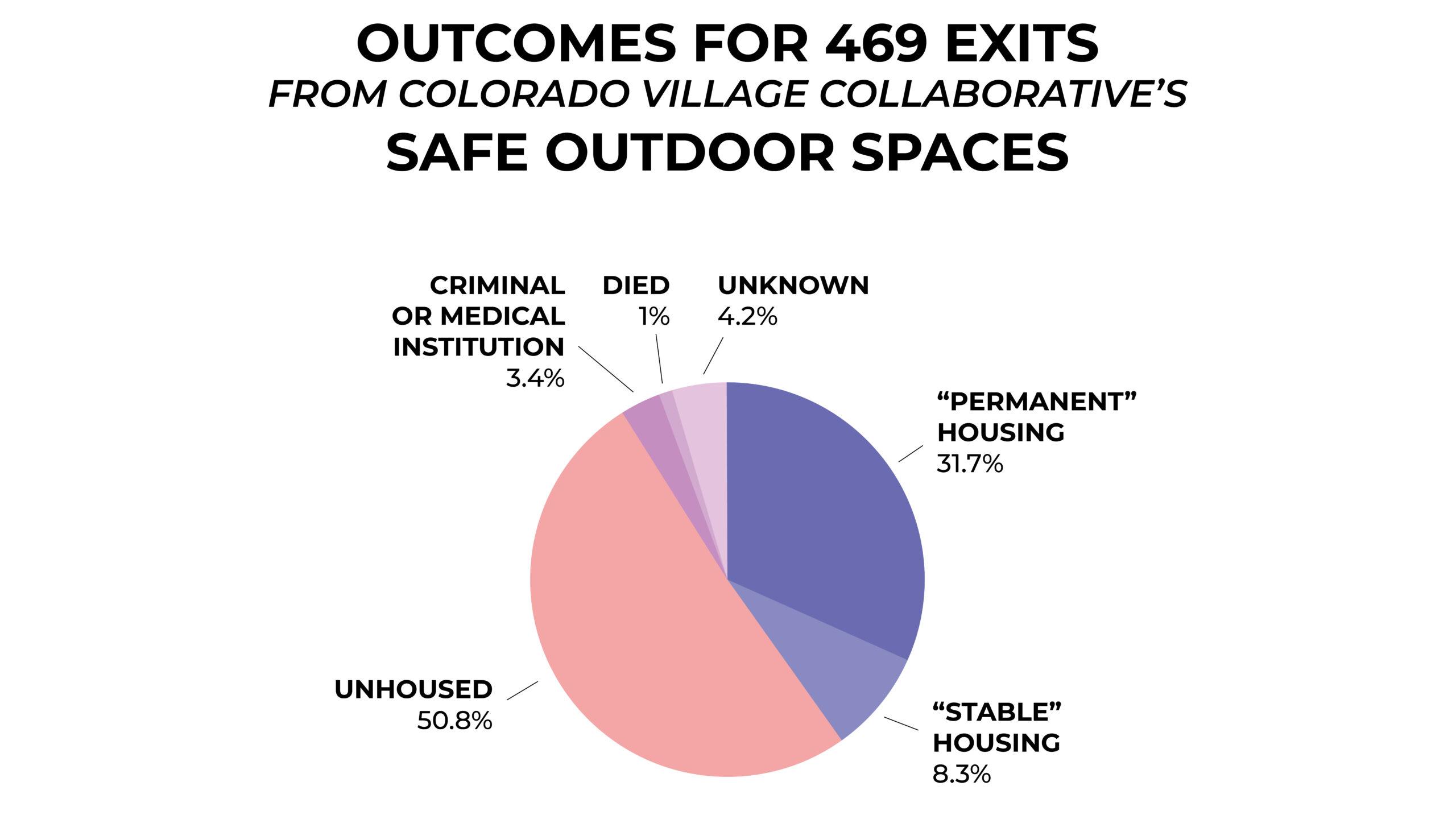

Data collected by the Metro Denver Homelessness Initiative (MDHI) suggests as many as half of the people who've stayed in CVC's SOS sites returned to homelessness after they left the program. The figures highlight how difficult it can be to move people out of crisis.

The data are collected by MDHI, who shares them with Denver's Department of Housing Stability (HOST), who shared top-line numbers with us.

MDHI did not comment on how they collect this data, nor would they say how CVC's successes compare to Denver's regular shelter system, telling us it's the city project and therefore the city should speak to its outcomes.

HOST said they could not share raw data behind the snapshot they sent us, since MDHI owns the records and because they contain confidential information about unhoused residents in the city.

Still, the numbers are worth looking at now because CVC's Safe Outdoor Spaces are the closest proxies we have to Mayor Mike Johnston's micro-community program, part of his bid to house at least 1,000 people by this year's end and reduce street homelessness in Denver. The city thinks it can do better when their new sites come online, but they face a nest of systemic issues that stretch beyond sidewalk encampments.

And though Johnston has set a tangible goal for his campaign, it will only begin to address the web of problems that underpin Denver's housing crisis.

The snapshot provides some insight as to where people go when they leave CVC's care.

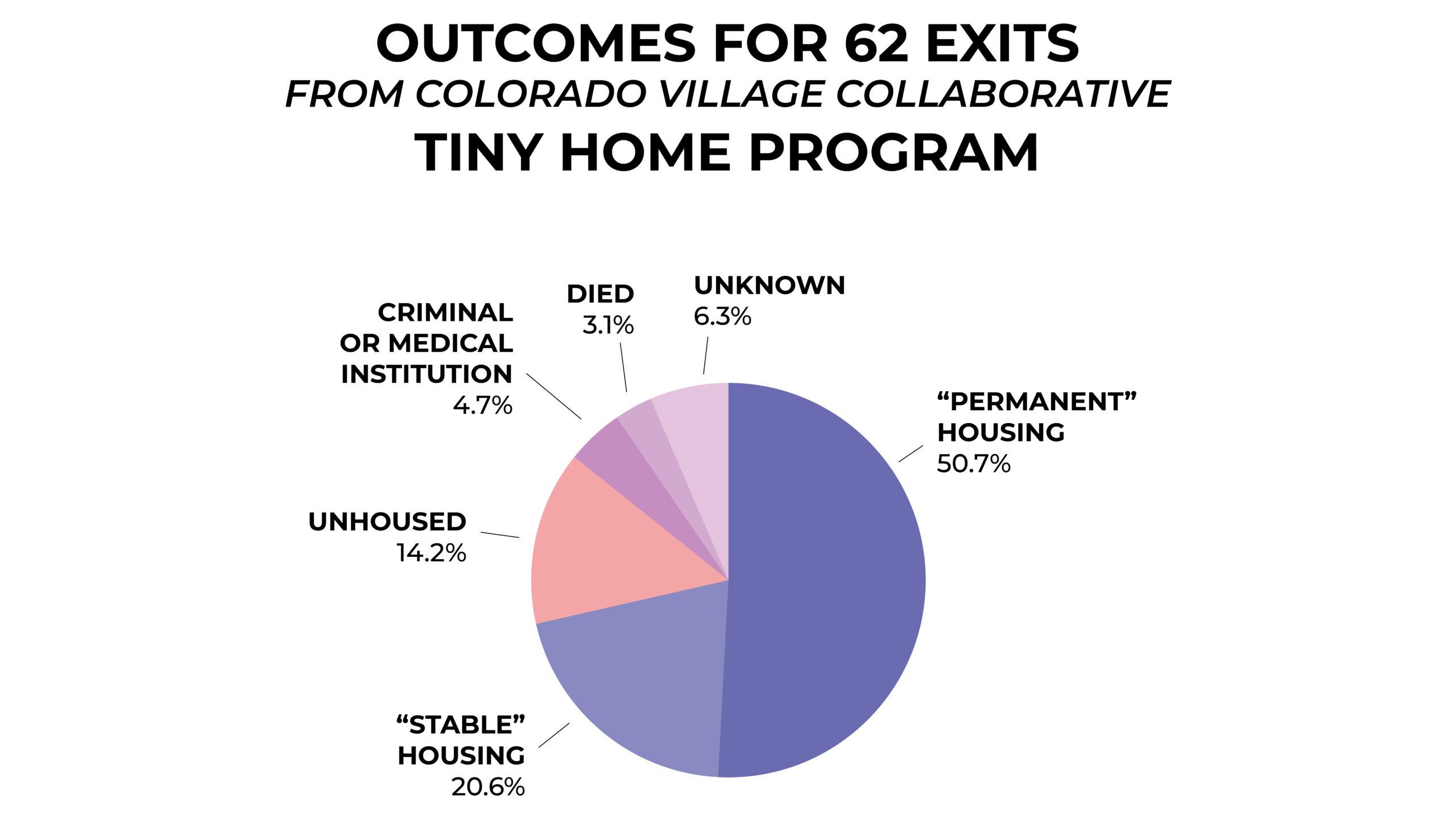

Overall, HOST's data shows 46.5% of household exits from both of CVC's programs resulted in homelessness. Broken down, that figure was 50% for SOS campsites, and 14% for the tiny home program.

It's worth noting CVC's tiny home program is significantly smaller than their SOS program. HOST's snapshot covers 469 exits from SOS camps since 2020, versus 62 from tiny homes.

Cole Chandler, who helped found CVC before he became Mayor Johnston's senior advisor for homelessness resolution, told us a lower success rate from a tent, compared to a house, should be expected.

"The greater degree of stability you're offering someone, the more successful they are in that unit," he said. "We always knew that the Safe Outdoor Spaces, they were serving a lot of people, they were offering more stability, but not quite as much stability as a tiny home, and not quite as much stability as non-congregated shelter hotel - and, obviously, not quite as much stability as a leased unit."

Johnston's administration has so far focused their finances on hotel rooms and tiny homes as they gear up for his micro-communities.

But SOS camps' 50% failure rate is also related to internal policy.

Chandler reminded us that there was enormous scrutiny on the SOS idea when former Mayor Michael Hancock finally allowed the program to begin in 2020. Chandler and his colleagues floated the idea for years, to no avail, but officials softened their stances once COVID-19 flipped the city on its head.

Though they won the mayor's support, some residents feared giving people safe spaces to sleep would bring danger to their neighborhoods, and pushback accompanied each new SOS site's creation. Chandler said the program needed to work to show the sanctioned campsites were better than doing nothing, so CVC took a strict posture in their operation.

"We designed some controls at those sites, which frankly made them higher barrier, which frankly made them harder for some people to remain successfully," he told us.

A study later found that crime decreased in areas where CVC's early campsites opened, and people living near them told us they came to appreciate them, despite early skepticism.

Cuica Montoya, who directs CVC's SOS program, told us most, if not all exits back to homelessness, resulted from someone being forced to leave the sanctioned camps for violating their rules. Residents are otherwise allowed to stay as long as it takes them to find a more permanent situation.

"I would say that we're planting seeds with folks that exit, so I don't think it's a fully negative experience for them. There are things that people need to work on still, and we're definitely down and ready the next time they want to reenter our program. And we reenter people all the time," Montoya said. "I don't ever want to judge anybody, especially the folks that have been exited from our program. Being somebody who has experienced homelessness myself, I struggled quite a bit and I might have entered the Safe Outdoor Space program a couple of different times before I got it."

Not everyone has seen that silver lining. Debra Ruiz, who lived in a couple of CVC's SOS camps, said she and others sometimes clashed with staff. She suspects those conflicts led to some people's wrongful ejection from the program, and that her own issues with staff led to her being "banned" from CVC property after she got into an apartment. The experience left her feeling that CVC's staff is not setting residents up for success.

"They're either throwing them out, or they housed them and they were immediately evicted," she said.

Sill, she has mixed feelings about the sanctioned camps, in terms of what they're supposed to achieve.

"It is a good program, but they need to be scrutinized more," she told us.

Chandler said Denver will work for higher success rates, but "success" is a slippery thing in this world.

While political challenges remain, the city has more latitude to open micro-communities with softer "controls" than Chandler helped create for CVC's SOS sites. Fewer people will be ejected, he told us.

"We are working to accommodate people's various needs, and really working to find ways to keep people in and on the path to permanent housing," he said. "We know forced exits will still be a part of it, but certainly we would want to seek to reduce those while maintaining the safety of the building and the safety of the surrounding community."

Forced exits can be hard to avoid. Nicole Martinez, executive director of the Las Cruces-based Mesilla Valley Community of Hope, told us it's a reality in the sanctioned campsite her organization has run for a decade. But defining success is tricky, she said, and graduation numbers only tell part of the story.

"What do you mean by success?" she asked, when we called.

On one hand, she said, her city relies on her nonprofit's Camp Hope to contain a problem that could easily spill over.

"What benefit is this to our community? You had 50 less people sleeping in downtown doorways," she said.

When the site opened in 2011, she added, unhoused residents began reporting fewer assaults, a sign that the camp was successful by another metric: It gave people somewhere safe to sleep.

Martinez said her nonprofit lacks the resources to properly track exit outcomes for Camp Hope's residents, but other programs show a wide range of results. A company that runs a sanctioned camp in Los Angeles has apparently placed only 2% of residents into permanent housing over the last few years. Meanwhile, Marc Eichenbaum, homelessness advisor to Houston's mayor, said 90% of people they move from streets into housing units remain housed after two years - his city generally skips temporary facilities altogether.

To judge his push to house 1,000 people by this year's end, Mayor Johnston's administration said they'll count anyone who gets placed into an apartment, and stays there for more than two weeks, as a success.

Still, Martinez said true victory is loftier; it would be a time when places like Camp Hope and Johnston's micro-communities are no longer needed. She's proud to sing her camp's praises, but she's cautious not to let people see it as a final solution.

"We don't want places to lose sight of affordable housing," she said. "For every encampment, you should have a huge plan to maximize affordable housing in your community."

That was Eichenbaum's message, too. This is a crucial moment for Denver, he said, adding residents should be both supportive and patient as the city ramps up their effort.

"Residents think that this is like a broken water pipe, or it's like the electricity going off, or trash that needs to be picked up - that they should just be able to call and this situation would be fixed. These are people, and by nature, people are very complex," he told us. "It's just not patience. It's support, too. Constituents should be supporting, if not demanding that government work together, and that government is coordinated and government is focused on endemic, systemic problems. And government is using best practices and investing in solutions that are going to get the biggest bang for the buck."

The Mesilla Valley Community of Hope and the city of Houston have both advised Denver in its sanctioned campsite effort.

Denver says housing and stronger systems should grow out of this micro-community push, which may help address every other crack people fall through.

Charles Homer has lived in the Salvation Army's Crossroads shelter, off Brighton Boulevard, for six years. He'd jump at a place of his own, if he could get one, but the right offer has eluded him.

"The only thing they've offered me is sober living. I don't even drink," he said, rolling his eyes from a lawn chair across the street from the shelter. "I want a regular place. It don't even have to be big. One room, that's all that has to be."

Homer and his buddies were up to date on the mayor's plan, but they weren't worried that Johnston's focus on sidewalk encampments will direct any resources away from them.

But Tim Thompson, who was sitting nearby with his dogs, Denny and Bruce, said he's heard grumbles in the warehouse.

"Nobody agrees with what he's doing," Thompson said. "He's not doing anything for us."

No matter how many people make it into Johnston's micro-communities, the entire system faces a practical bottleneck: There's just not enough available housing.

Chandler said the city hopes to add 3,000 affordable units each year during Johnston's first term, and that they'll rely heavily on dollars from generated by Proposition 123, a statewide initiative passed approved by voters in 2022 that sets aside hundreds of millions of state dollars annually for affordable housing development.

Beyond housing stock, Chandler said the city is gearing up to hire an army of case workers who will help people in micro-communities get into - and stay -- in their own units. He added Denver is also pooling money for a "rapid rehousing" fund, which would give some people the cash they need to lock down an apartment without a regular voucher.

For now, Chandler told us, these new resources won't help people like Homer and Thompson. Denver's regular shelter system already has money for rapid rehousing, so these new dollars will be focused on micro-community residents.

Still, Chandler said all of this work should create an improved landscape of services in the long run. Someday, micro communities could transform into permanent affordable housing, and the network of care that the city is investing in now should outlast Denver's shorter-term micro-community plan.

"We're building a stronger, more responsive overall ecosystem that we think is going to make us successful down the long haul. The micro communities we're setting up will be temporary. Many of these sites could later be developed into permanently affordable housing, like you've seen at previously existing CVC locations," Chandler told us. "Our very first site, 38th and Blake, we had a tiny home village there. It became an affordable building. People from that tiny home village actually moved into that affordable housing building."

But as the city works on this better ecosystem, some still struggle to hang onto stability.

For Ernie Madril, the system worked how it should have, until it didn't. A few months ago, he found himself homeless again. Nobody told him his voucher covered only a portion of his rent. Then, an eviction notice arrived at his door along with a bill for a few thousand dollars owed.

"I don't got that kind of money. They wanted the full amounts or get out, one or the other," he said.

Several of his neighbors, who also came from SOS sites, also received unexpected eviction notices, all for the same issue. Some, he said, went back to sleeping outside.

Madril told us he expected more help when everything fell apart. But his first case manager quit her job, and the person who replaced her hasn't been returning his texts. He might count as an SOS success story, since he did exit into housing, but he's pretty close to where he was before he entered a sanctioned camp.

"I'm tired. I can't - I'm just so frustrated that I just don't know what to do anymore," he told us. "I can't stay here forever."