Michael Weissmann, Ph.D., has long loved the little things in life. The tiny, flying, biting, buzzing little things that many people find appalling.

"A lot of people, they have this 'ew-bug-squish' attitude. They see a bug, they scream and they squish it without even getting to know it, without even learning about it," he told us. "And there's so much to learn about and so much to know."

He's the kind of guy who might gently cup a miller moth trapped in his home and release it outside. Maybe.

"Or feed it to the scorpion in the basement. It depends," he laughed.

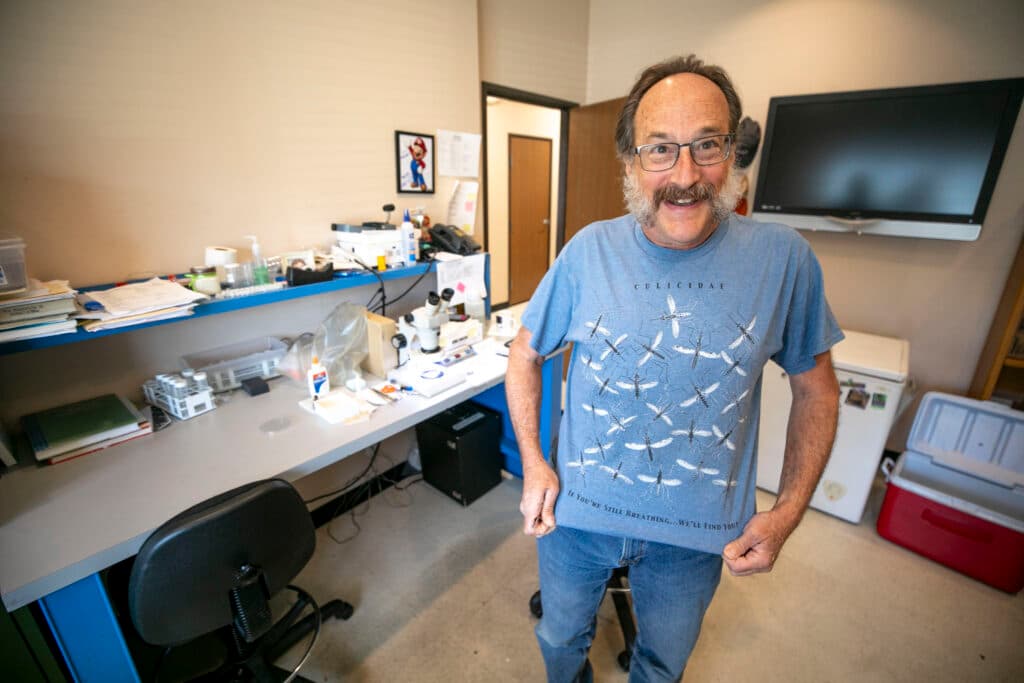

Weissmann spent his career studying what is perhaps the most hated of this group, the mosquito, and he is one reason why your warm summer evenings aren't completely ruined by them.

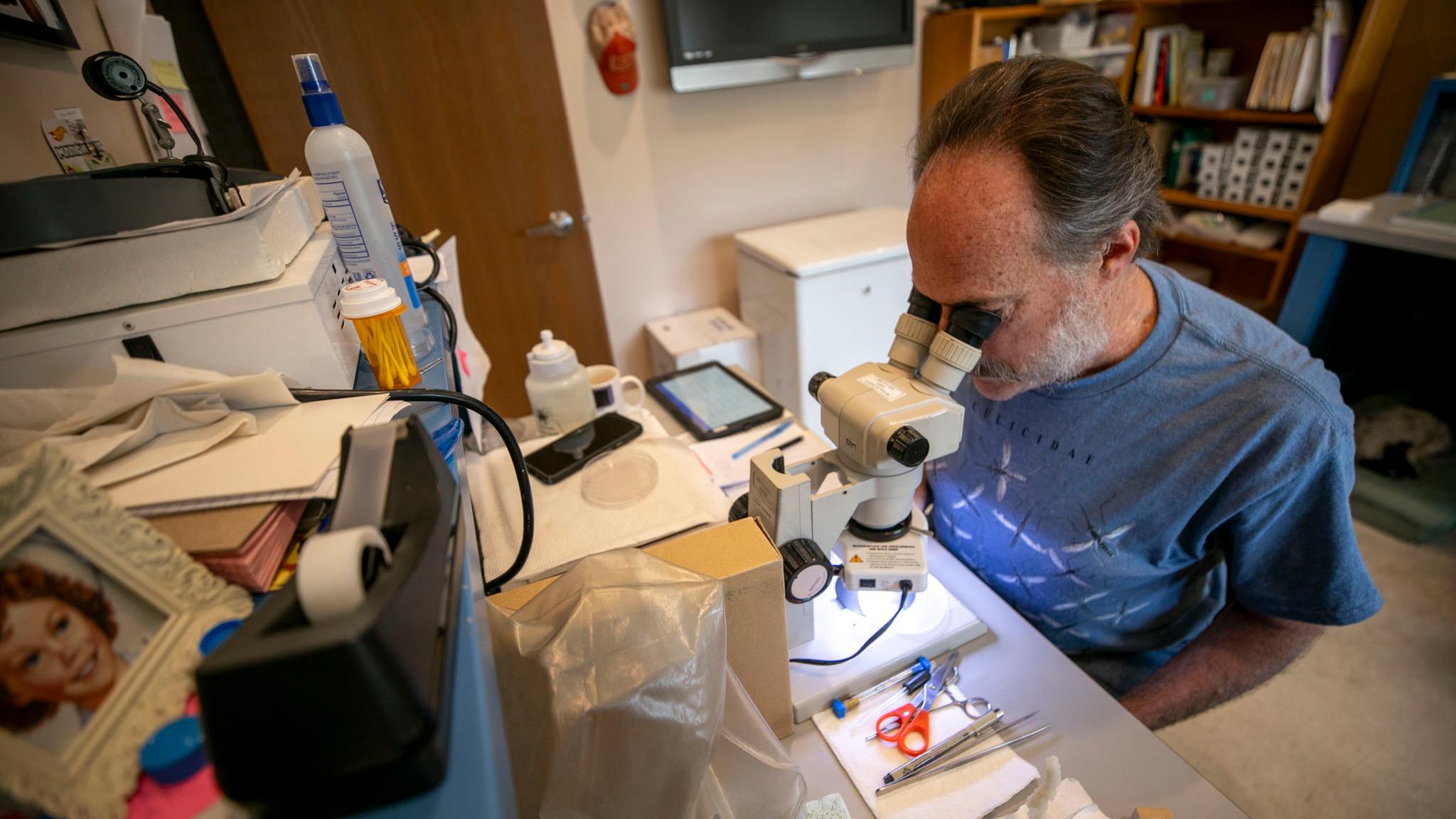

Officially, Weissmann spoke to us in his capacity as a zoology associate with the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. But he's also the chief bug expert with Vector Disease Control International (VDCI), a Broomfield-based company that captures, identifies and compiles data on mosquitoes for cities and scientific groups across the nation.

The work helps us understand more about these creatures and aids cities like Denver in keeping their numbers in check.

"You've got to know your enemy," he said, wearing a shirt covered with images of the six-legged pests. "Throughout the Front Range, if there was no mosquito control, you'd know it. You would know it. And the disease numbers would be higher and the nuisance would be higher."

The big concern is West Nile virus, which arrived in Colorado only 20 years ago.

Weissmann grew up in southwest Denver. When he was a kid, he remembers seeing trucks driving through town on summer afternoons, spraying chemicals we no longer use to try to manage mosquitoes.

"We'd ride our bikes behind it thinking, 'Oh, this smells cool.' But mosquitoes aren't flying at two in the afternoon, they're flying around sunset," he remembered. "So they're killing bees. They're killing butterflies. They're killing whatever happens to be flying."

That ineffective carpet bombing style of deterrents stuck with him as he pursued a career in entomology.

Then, in 2003, the mosquito-borne West Nile virus was detected in Colorado for the first time. He could see that officials were poised to do something about it, and he prayed they wouldn't rely on similarly crude solutions.

"I was concerned that the approach to West Nile control would be crazy, old-fashioned mosquito control. Kill everything. And it wouldn't be done scientifically. I got involved as an entomologist. 'Let's do this right. Let's do it scientifically,'" he said. "I'm pleased to say in Colorado, at least we do things right."

West Nile is the "leading cause of mosquito-borne disease" in the continental U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control. 8 in 10 people bitten by an infected insect won't experience symptoms, but some people do develop fevers.

About 1 in 150 infected people will experience serious symptoms, which can affect their nervous systems, cause meningitis and even result in death.

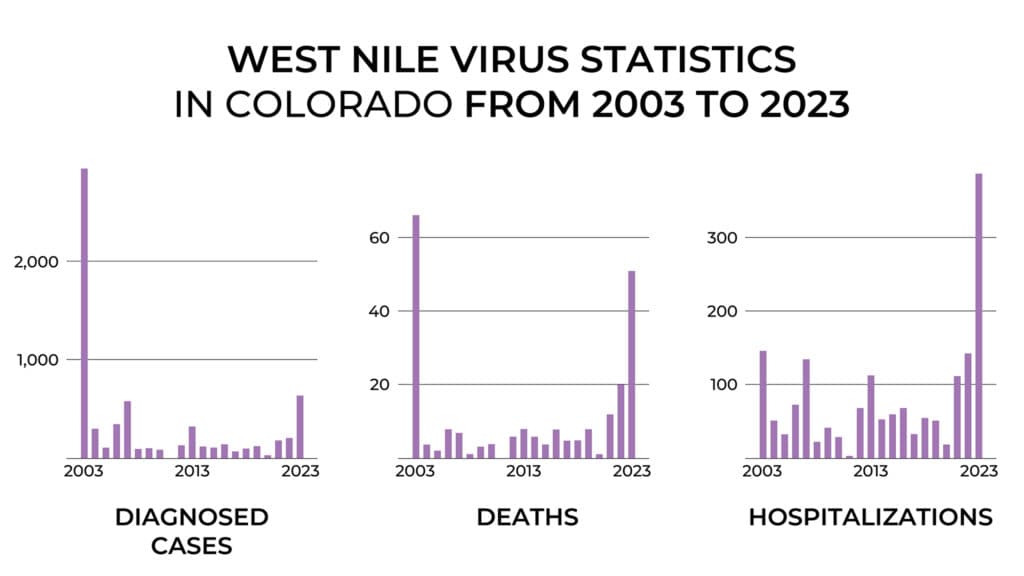

We were not prepared for West Nile when it arrived here. According to state data, 2003 was the worst West Nile year in Colorado history. Nearly 3,000 people got sick and 66 people died.

Colorado began working on that "right" response soon after the virus got here, and diagnosis numbers shrunk significantly through the next 20 years.

But in 2023, a massive snowmelt and heavy spring rains created conditions for a mosquito onslaught, resulting in 51 West Nile deaths and twice as many hospitalizations as were recorded two decades earlier.

State officials say things are looking better this year, though Weissmann said he'd be wary of anyone trying to predict the future.

"Ask me in October what kind of year it was," he said. "I can't predict the future. I'd be down on the track making real money if I could. This is not easily predicted."

Last week, Colorado logged its first West Nile infection of the year, diagnosed in a resident of Arapahoe County.

Denver is working to keep you safe, but there are things you can do, too.

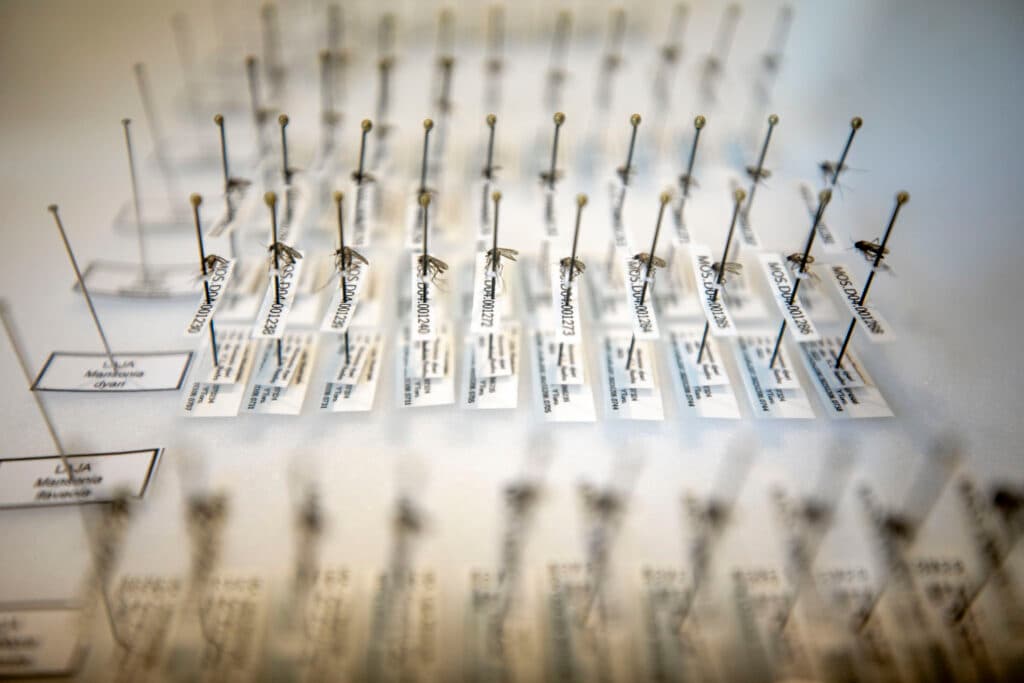

Weissmann's work at VDCI mostly revolves around a 30-year study commissioned by the National Ecological Observatory Network, helping them track U.S. mosquito populations across decades.

But the company also helps cities manage the insects in real-time.

Denver contracts VDCI to set up traps, which catch adult mosquitoes that are then identified and tested for disease. The findings are funneled to state and federal databases, which help Denver's Department of Public Health and Environment (DDPHE ) know when and where to try to intervene.

Mosquitoes thrive in wet shade. So, if you live near a park or a retention pond, you may find DDPHE environmental investigator Brian Tietze wading around nearby, working on that intervention with his trusty ladle.

"There are a lot of locations where it would be a two-foot wide channel, two feet deep of water, and maybe a mile long, and there would just be hundreds of thousands of mosquito larvae," he told us. "It's kind of creepy-crawly, horror-movie kind of look."

Tietze uses his "dipper" to take his own samples, searching for larvae and hotspots that need to be addressed. Between DDPHE and VDCI's surveillance, he said the city has identified about 70 sites that regularly become mosquito dens.

When Tietze finds such a hotspot, he may sprinkle some poison into the current. It's a compound that "burns holes through the mosquito larva stomach" but doesn't impact other species that may be present.

If a lot of mosquito-eating predators are present, he may stand aside and let nature handle things on her own.

Though DDPHE is working to keep the bugs away from your barbecue, Tietze said people might also think about the "four Ds" of protection: rethink going outside at dawn and dusk, consider dressing in long sleeves and pants, dump out standing water in pots or kiddie pools, and don't forget to use a little deet to deter the tiny biters.

The part about dumping is a biggie, Weissmann told us, because mosquitoes need just a little bit of water to take over your backyard.

It's one reason why he's unsure what kind of West Nile year we'll have in 2024. We've had a relatively dry spring and summer, but so much of this is driven by human activity.

The trees we planted for shade, the irrigation systems we created for our crops and the ways we've reshaped our landscape have all contributed to West Nile's existence here.

And that, he added, why we must work to keep the flying pests at bay.

"In places like Denver, where we've changed the habitat so much that mosquitoes are thriving in places where they didn't exist before, I think we have a right to fix what we broke," he said. "And we should fix what we broke, especially now that West Nile's here."