Billionaire Nuggets and Avalanche owner Stan Kroenke and his company Kroenke Sports and Entertainment have dreamed up a plan to redevelop 65 acres of Ball Arena parking lots into an entirely new downtown Denver neighborhood.

Right now, the lots mostly sit empty, underused slabs of concrete for suburbanites’ cars. Occasionally, Cirque du Soleil sets up a big tent there. During games and events, fans drive into the city, park and then leave. Those 65 acres go unused until the next event.

If Kroenke’s project goes through, it would bring roughly 6,000 units of housing — as well as hotels, restaurants, art and a new concert hall — to an otherwise yawning gap in the city center.

For those fearing parking will go away, it won’t. Parking will be concentrated in garages, instead.

With greater connectivity between the surrounding neighborhoods, bikers and pedestrians will have a safer entrance to the area than they do now. Public transportation will be also easier to access.

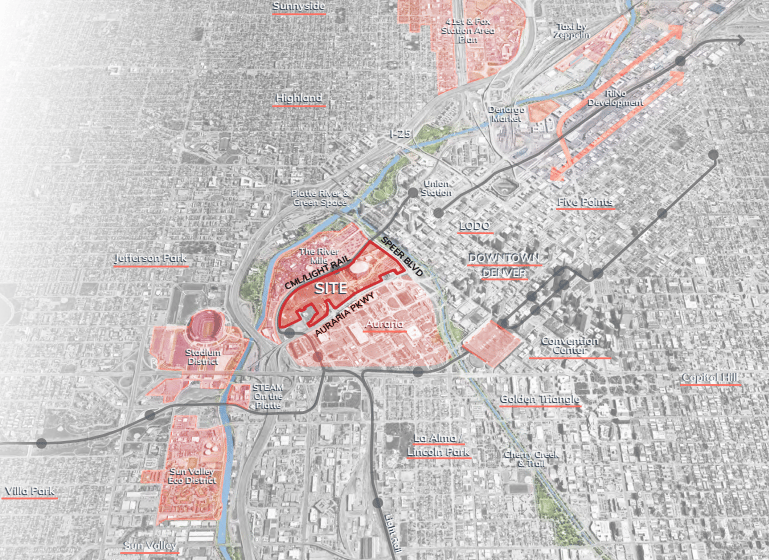

The project will join the Sun Valley developments, the River Mile, a reimagining of Speer Boulevard, and a reboot of the Auraria Higher Education Center that all aim to expand the city’s skyline and double the size of downtown Denver.

But Kroenke needs more than an ambitious plan. He needs community support.

Most urgently, the company needs an inked, legally binding contract called a community benefits agreement.

That document, if monitored by neighbors, will ensure the city’s residents get what they want from the development.

But what community? The site is a big island of concrete cut off by major roadways. Who really cares about that land?

True, there aren’t a lot of immediate neighbors or residents and businesses on the land. But there are neighborhoods that would be within walking distance of the Ball Arena project, if connectivity across Speer Boulevard, Colfax Avenue and the train tracks was improved.

Those include people from Lower Downtown, Sun Valley, La Alma Lincoln Park and the Auraria Campus, among others.

Residents, nonprofit leaders, educational and cultural institutions and business owners in those neighborhoods say they have a huge stake in the future of the land. And they have a big vision of what Kroenke’s project might bring.

To pull off the project, which could take 25 years to build out, Kroenke needs City Council to approve a massive rezoning. That will likely require community support.

And for community members, organized under the Ball Arena Community Benefits Agreement Committee (BACBAC), to testify in favor of the project, they’ve made it clear: They will only do so if they have a community benefits agreement.

If that’s not signed, many would oppose the project.

“For a project of this scale, it's even more important to have a CBA,” said Susan Powers, president of Urban Ventures and co-chair of the committee. “We want an organization from the community that has the ability to keep an eye on it.”

So what does the community want, anyhow?

BACBAC is looking for better connections between neighborhoods and the city.

“When you think about that kid in Sun Valley or Lincoln Park who wants to go experience this massive investment that the city is making in, on and along the river, how are they going to get there?” asked Simon Tafoya, a La Alma Lincoln Park resident and co-chair of the committee.

The answer: improved infrastructure for pedestrians and bikers.

The members want Kroenke to create open space that’s available to public, so people from nearby neighborhoods can enjoy the area.

They hope for more economic opportunities, including jobs for people in nearby neighborhoods, support for small, local and minority-owned businesses and places those businesses can rent for below-market prices.

The group also wants affordable housing that exceeds how much is required by city law. That housing should be focused on keeping people at risk of being displaced within the city. And it should also be affordable for the long term and distributed throughout the community.

Finally, the group wants the development to include cultural amenities honoring the history of Indigenous communities and people who once lived in the Auraria neighborhood but were displaced when the Auraria Higher Education Campus was built. Those amenities should include cultural spaces and programs for children and families and funding for public art produced by BIPOC artists.

Powers says the community is digging into the weeds to make sure that what looks like a well-planned development is actually responsive to community needs. The goal: substance rather than marketing.

Members of the BACBAC are optimistic Kroenke will sign a community benefits agreement. And when the company does, the neighbors will form a nonprofit to ensure Kroenke honors the terms of the contract over time. If the company fails to, the group will take legal action.

What does the Kroenke say about that.

Matt Mahoney, the senior vice president of Kroenke Sports and Entertainment, says that for the nearly three years his company has been working on the project, they’ve been talking with the community.

“If you're really engaging with the community, listening intently and honestly with the surrounding community, you end up with a development plan that reflects what the community really wants to see on a property,” he said. “ And if you're successful with that, once you start building, once you start developing what you said you were going to, what the community wants you to deliver on, it'll just be that much more received and that much more successful.”

Kroenke Sports and Entertainment has met with the committee roughly 20 times and has agreed to build 18 percent of the housing units as income-restricted housing. That will be geared for people making an average of 70 percent of the area median income and will include housing for families.

In total, he said, the project will include roughly 6,000 units of housing, with more than 1,000 of those will be designated as affordable housing.

The project will be built out in three phases, the first including hotels and a mid-sized music venue with roughly 5,000 seats that would rival Anschutz Entertainment Group’s Mission Ballroom, he said.

It will also include a three-acre park, what Mahoney described as “our neighborhood park for Downtown.”

Most of the housing will be delivered in the second and third phases.

Closer to Sun Valley will be a transit-oriented development with two light rail stations and high-density development nearby.

Mahoney’s glad to be hearing from people across nearby neighborhoods, in part, because the project will be so transformative to the city center.

“As you look at the growth of downtown, from RiNo into the Central Platte Valley with Riverfront Park and Union Station with River Mile’s plan in place and Ball Arena now in planning, you can just feel the growth of Denver happening in this area. It's hit a lot of folks’ radar for good reason,” he said.

“We're talking about 65 acres of just parking lots,” Mahoney continued. “And when you start talking about, ‘Hey, let's create a neighborhood, a new neighborhood, for Downtown,’ we wanted to have input from other neighborhood groups to say, ‘What would you want to see here? If you were going to come to the arena neighborhood property, what would you want to see on property? What’s important to you? What would bring you here? What would keep you here?”

What’s next?

Right now, BACBAC is passing drafts of the community benefits agreement back and forth with Kroenke.

“We’re in the weeds,” Powers said — and that’s necessary to ensure the community relations aren’t just marketing, but have substance.

If a deal is signed, the rezoning, which already passed the city’s planning board, will likely be considered by the full City Council in the fall.

Mahoney said Kroenke is grateful for the continuing discussion and anticipates signing an agreement soon.

“Folks that are on the BACBAC committee, they're downtown people,” he said. “They love downtown Denver. They're passionate about downtown. They want to participate in Denver's future, and this is part of Denver's future. So it's been pretty cool.”