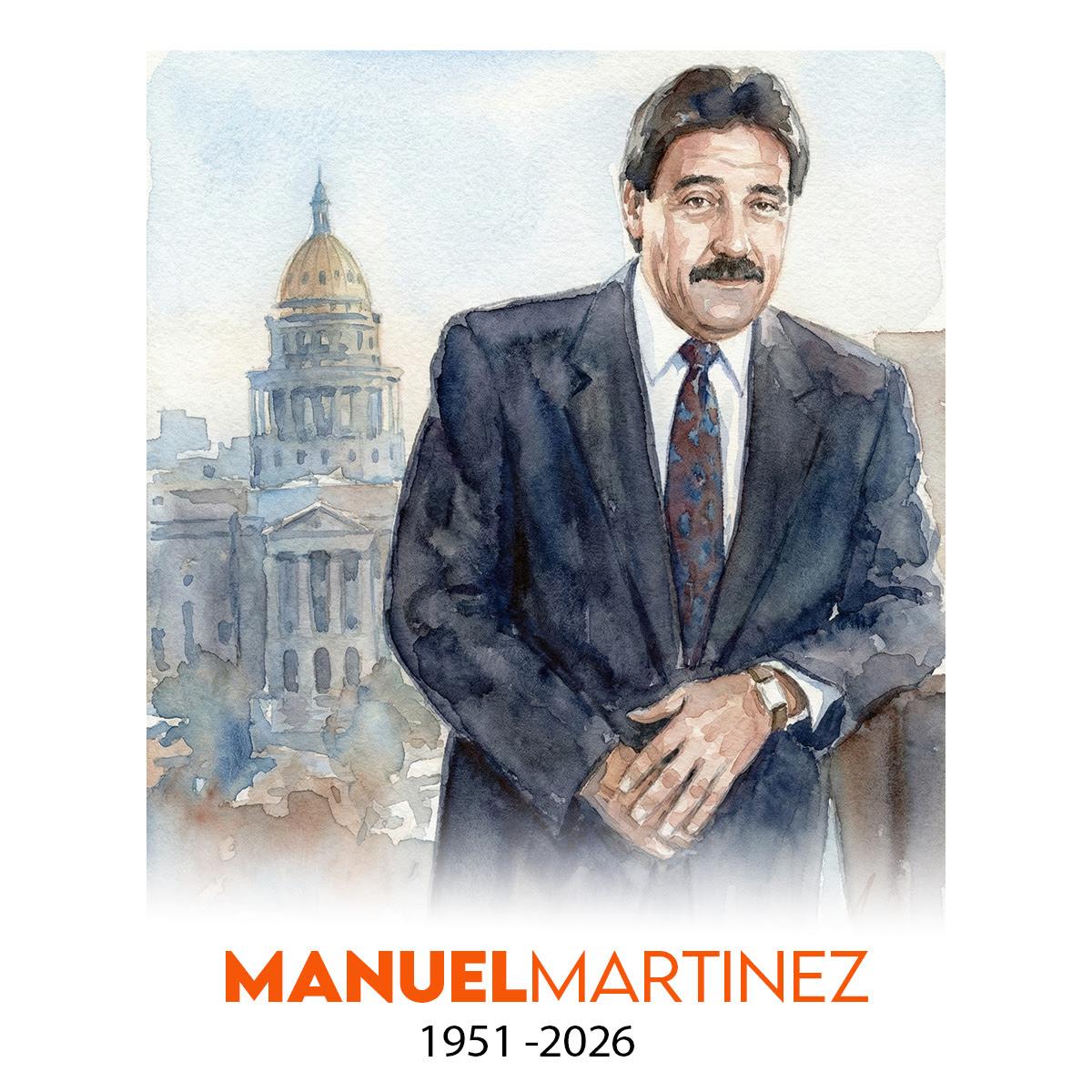

Cherry Creek lost one of its longest tenured residents this month.

Nancelia Jackson moved to the neighborhood as a baby, in 1926, before Temple Buell built a mall there and before the neighborhood became chic and expensive. Back then, it was an enclave for Black Denverites, outside of Five Points' redlined borders. She'd spend nearly a century living there, watching the city and the surrounding blocks transform around her.

Jackson died on Aug. 18 at her home on the block of Garfield Street where she lived for 98 years, just two months shy of her 100th birthday. In July, she had received a letter from Vice President Kamala Harris — a day before President Biden dropped out of his race for reelection — wishing her an early happy birthday.

In 2017, Jackson regaled us with memories of her neighborhood.

Denver was still segregated when she was young. Though she could remember a time when she was only allowed to watch movies from the Esquire Theatre's balcony, she didn't talk about the city's past with disdain. She looked back, instead, with fondness. Her neighborhood was somewhere she knew she belonged.

"Cherry Creek had a little colony of Black people," she told us then. "We were here first."

The area was prone to flooding in the early 19th century, before the Cherry Creek Dam was completed in the 1950s, and it was home to a garbage dump that served the burgeoning city. Jackson's grandfather, William Pitts, built the family's first home on a high ground; she could remember watching floodwaters spill over the Cherry Creek's banks when she was a kid.

She told us her neighbors were sparse enough that she could count them on one hand. The neighborhood felt far removed from downtown, and she said she never noticed the dump.

In 2017, she told us there was no place she'd rather be.

"I'm still here," she said, "and I don't plan to go anyplace, either."

She was known as "The Grand Dame of Garfield."

Jackson's ties to Colorado's Black history go far beyond Cherry Creek.

While Pitts, her grandfather, was known for developing homes in the neighborhood in the early 1900s, he's more recognized for his contribution to Lincoln Hills, a resort town near Nederland that specifically catered to Black vacationers.

The cabin he built for his family there in the 1920s still stands today. Jackson and her family used it for family reunions and weekend getaways. Her son, former Denver County Judge Gary Jackson, has become an active spokesperson for ongoing historic preservation efforts at the site.

"I remember my brother and I being three and four years of age, sitting on the rock that is just east of the cabin," he told us last week. "My mom has my brother and I in her arms."

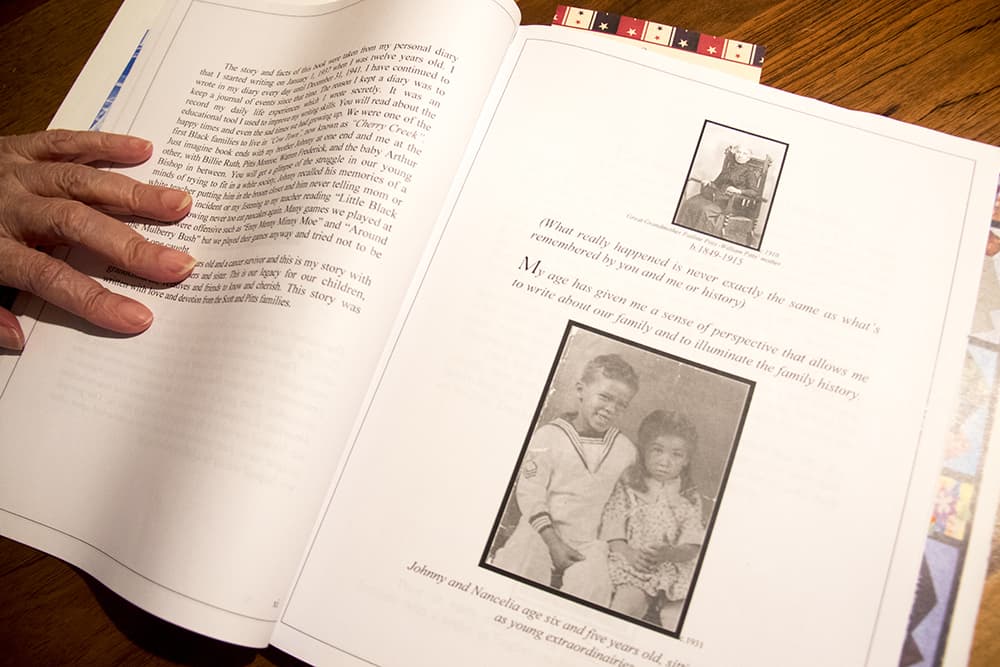

It was a special place to Nancelia Jackson, even as a kid. When she was 14, she penned daily diary entries, documenting her time there with her family. That journal, Gary Jackson told us, is now accessioned in the Museum of Boulder, and is being digitized for the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

The firsthand account preserves memories of a place that was crucial for Black Coloradans, Gary Jackson said, that represented their hopes for equality and a sense of belonging in this state.

"It was having the American dream," he said. "It was important, because so many Black people were working hard jobs. It was an opportunity to rejuvenate yourself. It was also, when I look back at it, spiritual — spiritual in terms of being in the wilderness and being close to nature, and being in a place where there was no fear, there was no conflict."

Nancelia Jackson's son will remember her as his fiercest advocate.

In the 1970s, fresh out of law school, Gary Jackson got a job with the Denver District Attorney's office. He was the only Black prosecutor in Colorado at the time, and his arrival rankled some in the city.

"I had an afro that was three or four inches long. That afro created great consternation to those within the political establishment," he remembered.

A state Supreme Court judge was particularly annoyed, Gary Jackson recalled, and penned an open letter in The Denver Post decrying how this new attorney presented himself. Nancelia, by then a housewife, wasn't having any of that.

"My mother reacted to that by sending a letter to that Supreme Court justice, saying that I should be judged by my law school grades and the work that I did in court," he told us. "That took courage."

The justice apparently felt the sting of that maternal clapback. Jackson said he and his mother were summoned to the high courthouse, where the justice apologized in person.

Gary Jackson has been recognized in his own right, for his work as a lawyer and a judge, and for co-founding the Sam Cary Bar Association, the state's oldest organization serving minority attorneys. All of that success, he said, is due to his mother's backing.

He'll remember her for her dedication to her community in the Scott United Methodist Church, for her contributions to preserving local history, for her 30 years volunteering at Denver election stations — and, of course, for supporting him for so many years.

"My mother was my greatest advocate, my greatest supporter," he told us. "If it were not for who she is, I wouldn't be who I am."

A celebration of life service will be held for Jackson on Aug. 28 at Scott United Methodist Church, 2880 Garfield St., at 11:00 a.m.