Local zoologist Frank Krell remembers the first time he saw the photograph of the mummified dung beetle, wrapped in gauze and discovered in an ancient Egyptian tomb.

“Probably a decade ago, or so,” Krell said. “It's the largest dung beetle species in Northern Africa.”

The specimen was 2,000 years old. Krell had worked with older, fossilized insects, but this bug’s connection to a distant culture was of particular interest. It was still in his mind, years later, when an archaeologist reached out for help describing it.

“They said they need somebody who knows dung beetles,” Krell said. “I said, ‘Yes, I can do that. And I would like to do that.’”

So, Krell got to study the beetle mummy.

He joined a dozen other authors on a forthcoming book, “Animal Mummies,” which describes 13 wrapped specimens held in the University of Amsterdam’s research collection: cats, dogs, birds, fish, a shrew, an alligator and the dung beetle — better known as the scarab.

The book catalogues each species’ zoological particulars, how they were mummified and how they were depicted in ancient Egypt’s pantheon and symbology.

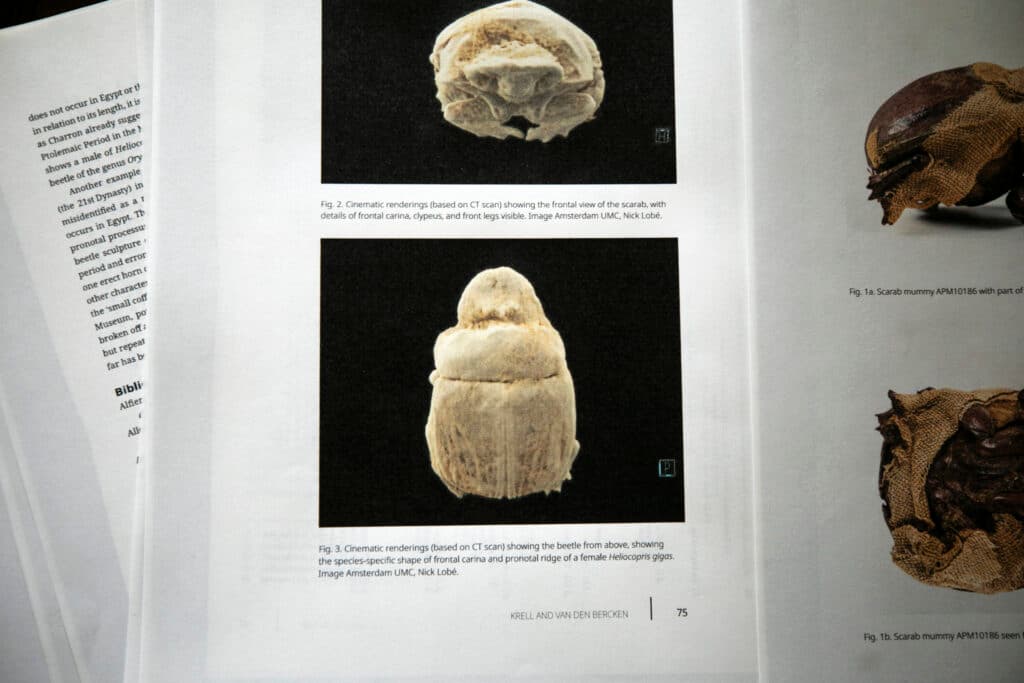

Krell, a dung beetle expert who served as the Denver Museum of Nature and Science’s entomology curator for 18 years, joined ancient Egypt expert and lead author Ben van den Bercken for the scarab chapter. Van den Bercken handled the cultural context, while Krell studied photographs and CT scans to identify the exact species.

It turned out to be heliocopris gigas, which is still found in Egypt today. He was hoping it might be another variety, which he hypothesized disappeared along with North African elephants when the Roman Empire still ruled.

It wasn’t a breakthrough, but it was still a thrill, Krell said. Though scarab depictions were “ubiquitous” in Egyptian culture, he said it’s very uncommon to find actual, ancient beetles.

“The most frequently made mummies were cats and ibises. They made millions of them, actually. There are millions of them buried. It was a big business,” he said. “It's very rare having mummified beetles.”

He also dug into scientific literature, looking for mentions of other similar discoveries. Many beetles were found encased in tiny coffins, he learned, but there were usually more boxes than specimens.

“Often the coffins survived and the beetle inside didn't,” he lamented.

In ancient Egypt, Krell found people he could relate to.

At Krell’s home, 40 minutes north of Denver, pictures of bugs hang on the walls. A bust of Charles Darwin stares down the hallway. Microscopes sit casually on furniture, used both for specimens he collects and to study the occasional intruder.

“We have the odd camel spider in here,” he said.

“Yeah, I like to collect those,” Victoria, the eldest of his three daughters, added.

It’s an affinity that she and her dad both know isn’t shared by most.

“It's pretty normal for kids to be grossed out or freaked out about bugs and stuff, but that's not something that my sisters and I grew up with,” she said.

Krell said a bug-positive viewpoint isn’t particularly common across history, either. The Egyptians are an exception, he said. It’s a big reason why he was excited to join van den Bercken’s project.

“I'm interested in all the cultural connections between my beetles and humans, and the Egyptian culture was a culture that took insects probably most seriously and considered them most important, of all cultures,” he said. “If you look in their temples, where the hieroglyphs are, there are scarabs everywhere! So that was important.”

Animals were offered as tributes to Egypt’s gods. The scarab, associated with Atum, source of all creation, and Re, god of the sun, was an “important symbol of rebirth and regeneration,” Krell and van den Bercken wrote in their chapter.

So it was fitting, Krell told us, that a photo of the scarab made the book’s cover. It made him proud, and it’s motivating him to spend more time chronicling insects of the ancient world.

But there’s something else bugging him, he added, which will make it hard to turn away from antiquity. Egyptologists historically did not work with entomologists, so the academic record is full of taxonomical errors. Correcting each of them, he said, will be a delight to keep him busy for years.

“Publications with wrongly identified animal mummies and animal sculptures are plenty,” he said with glee.