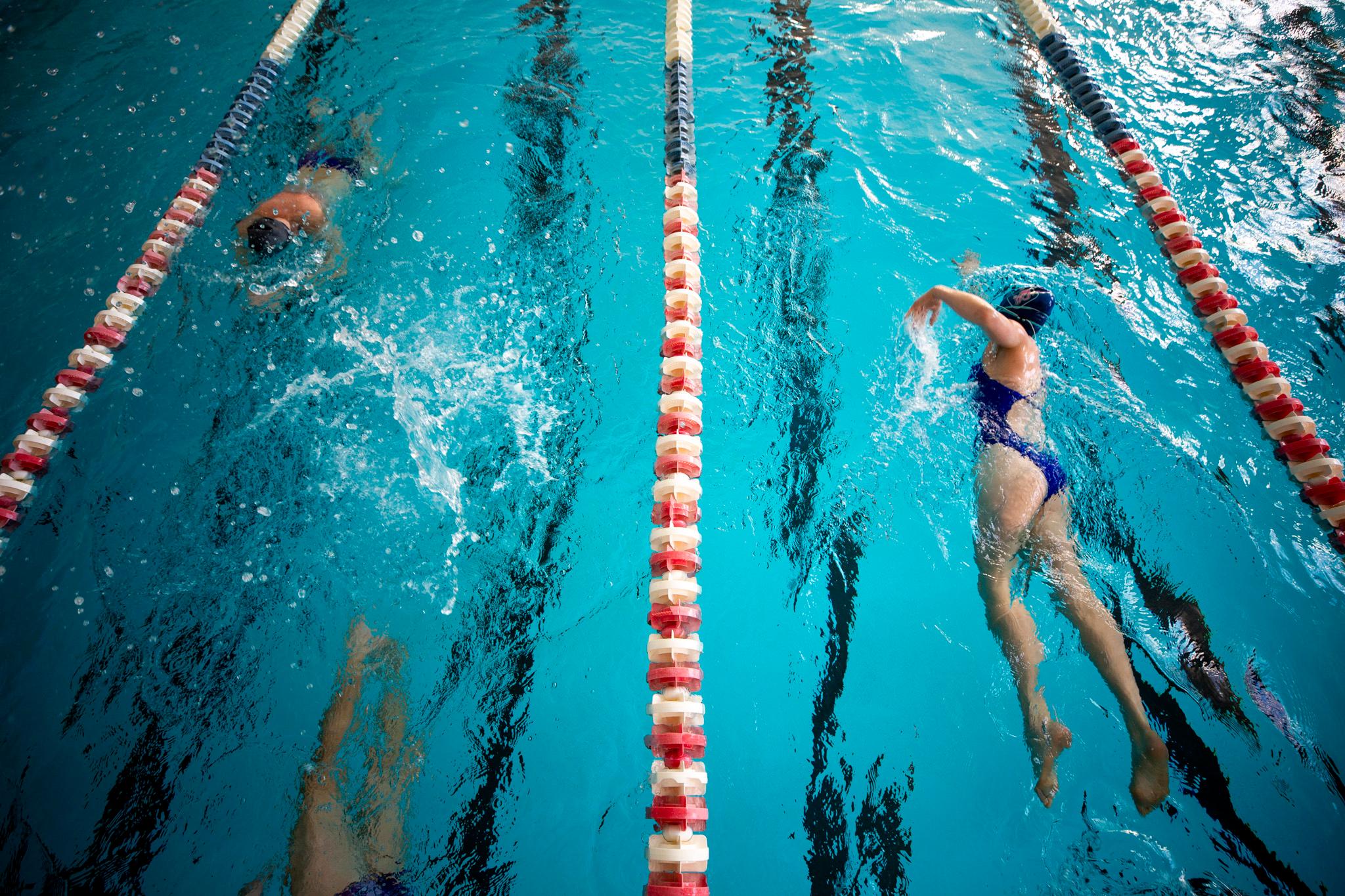

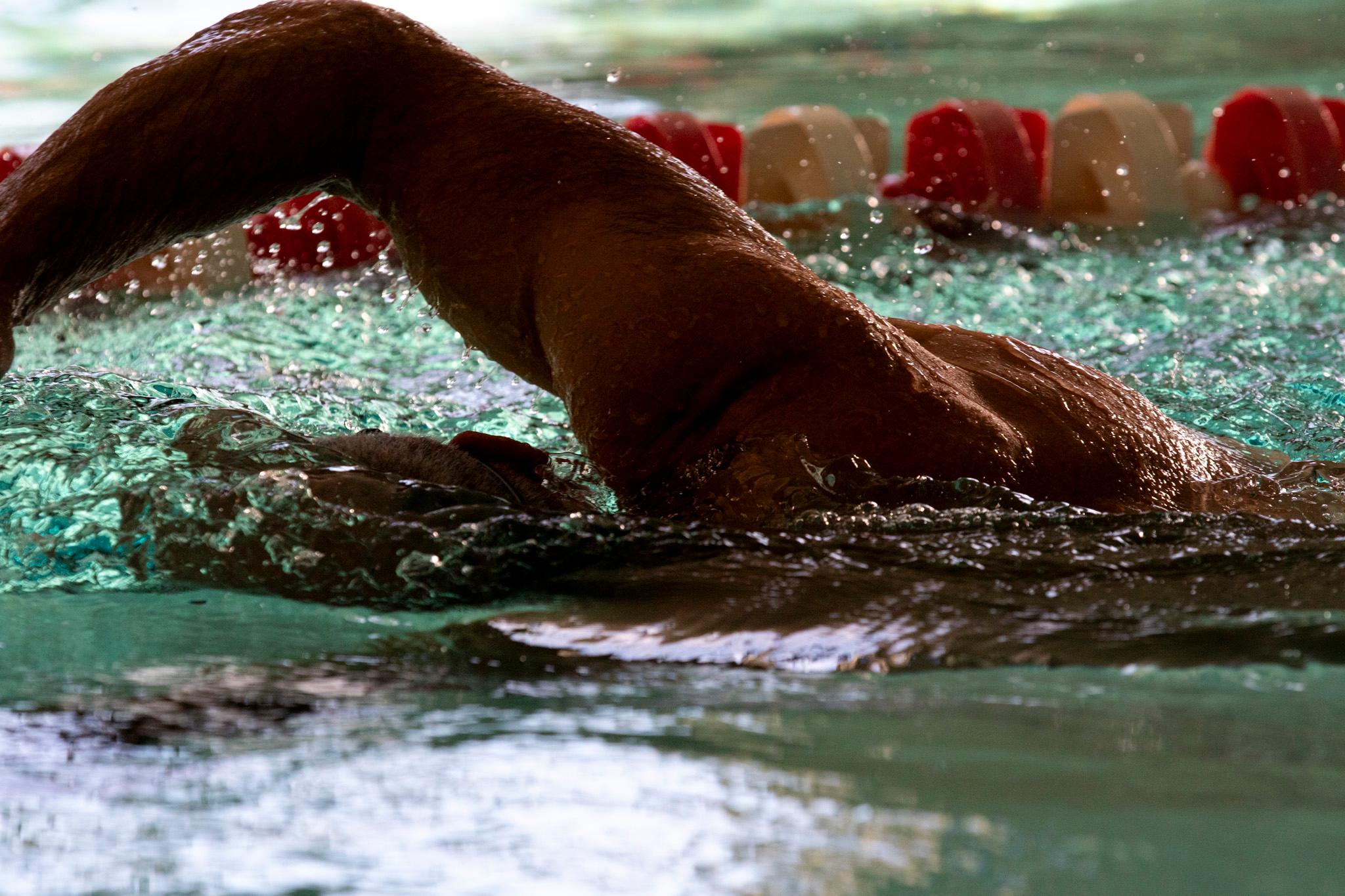

On a cold Saturday morning in January, swimmers with Squid — Swimming Queers United in Denver — changed into swim caps, goggles, Speedos and race suits and splashed into the Abraham Lincoln High School pool.

Normally, the iconic Denver team would be practicing at a rec center. But in December, Denver Parks and Recreation quit renting space to Squid and all other private teams. Now, public school pools are the only places the group is welcome in Denver — and availability is scarce.

The team used to practice multiple times weekly. Now they’re only swimming together once a week — far too little for swimmers who are training to compete in the Gay Games this summer.

Squid swimmers are baffled: After more than three decades of partnership, how could the parks department cut ties, especially when the national political climate has turned so hostile toward the LGBTQ community?

The timing of the city’s decision to boot private swim teams was particularly bad. The team lost access to Rude Recreation Center — just before the new year, when pools would be flooded with people who made New Year’s resolutions. Washington Park’s pool was closed, too, putting extra demand on other rec centers. Outdoor pools were shuttered for the winter.

Members are frustrated that athletes in other sports continue to rent parks and recreation facilities when Squid cannot.

“This is at least unequal treatment and at worst discrimination,” longtime member John Hayden said.

Which private swim groups have ‘a benefit to the city’ — and thus get pool access — is controversial

The reason for cutting ties has nothing to do with the LGBTQ community, John Martinez, the deputy executive director of Denver Parks and Recreation, told Denverite. All other private swim teams also lost practice space.

“One of our most popular assets is our pools,” Martinez said.

Demand is high and private groups like Squid are not the priority — even if they pay.

“To exclude the public to have private rentals is not in line with our mission and vision any longer,” he added.

But members of Squid say their presence as an LGBTQ swim team gives people who otherwise might not feel comfortable in the pools a chance to practice together and build community.

The team says it makes good use of the lanes, with multiple swimmers sharing lanes to save space.

Other outside swim groups still rent the facilities. For example, the department works with Vive Wellness, whose CEO Yoli Casas provides swim lessons — a service the parks department also offers.

“She is teaching kids of color how to swim,” Martinez said. “She has access to our pools, but it's through a formal agreement. And that's the direction where I want to move to — from more of the one-off facility rentals to a long-term partnership agreement that has a benefit to the city.”

But Squid maintains it meets those criteria and is making its case to Parks and Rec.

“I know what a positive impact Squid has had on so many people’s lives in Denver,” Hayden said. “Why wouldn’t the city value that?”

Squid has proposed alternative ideas: paying extra to swim outside normal pool hours, practicing in less frequently used rec centers, becoming an official city program.

But so far, Parks and Rec has said no, though it’s considering how it might work with outside groups in the future while maintaining priority for public use.

The team already practices water polo in Lakewood, outside of its hometown. Now, it fears it may also have to bring its swim practices to the suburbs.

Squid began when Colorado was still the ‘hate state’

In 1993, a group of gay swimmers met during lap swim at the Congress Park pool. They decided they wanted to train together for the 1994 Gay Games to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the Stonewall riots.

Back in the ‘90s, Colorado got the reputation as the “hate state.”

“We were actually contending with Amendment 2 at the time, which sought to strip the rights of LGBTQ people and make it absolutely clearly legal to discriminate against them,” Hayden said.

Being a part of a gay swim team — or any group at the time — put people at risk of discrimination, he recalled.

“So forming the swim team and saying that we are here and we are going to be open, and we are going to be supportive of LGBTQ people and provide a safe and healthy place for them to meet and exercise and learn to swim and have community was a big step and a big risk, and people took it,” he said.

Squid started swimming with the University of Denver masters team and eventually started practicing at the rec centers.

Hayden’s husband is one of Squid’s founders. One time, the couple hugged each other after practice.

“We actually had the rec director at the time tell us that there would be no public displays of affection in the pool, and all we did was a hug,” Hayden recalled.

That policy didn’t last long.

“The mayor at the time, Wellington Webb, who had a gay son, came out right away and said, ‘No, we're not going to have that in our pools. We're not going to have discrimination in our pools. These people will be welcome in our pools,’” he said.

Since the ‘90s, the culture of the LGBTQ community — and the understanding of gender itself — has changed. These days, Hayden said, it’s challenging to tell who’s part of the LGBTQ community and who is an ally.

“We actually attract a tremendous number of heterosexually identified swimmers to the pool because we're a fun swim team,” Hayden said.

Squid is growing even as practices are threatened

Rochelle Novilla, 33, wrapped her last lap and toweled off. She had just completed her first practice with Squid. She was ready for a breather.

She moved to Denver two years ago from New York, attracted to the state’s outdoors culture. Over the holidays, she found herself eating dessert for breakfast, lunch and dinner and decided she needed a change. So she signed up for the Boulder Half Ironman, bought a race bike and started training.

On this Saturday morning, she found herself in the lightning lane and got some tips on her freestyle stroke from coach Jenna Fossum.

Novilla was impressed that a couple dozen people woke up and showed up at the pool at 9:30 a.m. on a Saturday morning — creating team camaraderie in a sport that is often done alone.

“It's a different dynamic when you swim with people,” she said. “Not only are you getting splashed in the face, but … you have to synchronize in the lanes that we're sharing. I made a friend today in my lane — because we have to coordinate.”

New members show up at nearly every Squid practice. The team is a safe landing pad for LGBTQ people migrating to Denver for the state’s legal protections and welcoming community.

Orion Richmond moved from the Bay Area to Denver in 2015 and joined Squid shortly after. Around 2018, he helped found Squid’s water polo team.

“There's something about swimming that is great for the body, great for the mind, but more importantly, this team is an LGBTQIA+ inclusive team, meaning we welcome everyone here, and we don't exclude anybody,” Richmond said. “And that's important for folks to find community who might feel isolated at home or isolated where they work.”

With federal policy targeting the LGBTQ community and transgender athletes in particular, Squid’s offerings are every bit as urgent as they were back in the ‘90s, Hayden said.

“We're excited to be able to offer that safe and healthy place again to people who are maybe not able to find that in their homes in other places,” he said.

He just hopes they can share that experience multiple times a week — not just on weekends.