Updated at 2:24 p.m. on Thursday, Feb. 5, 2025

After the sun set on the last Monday in January, Lakewood housing manager Chris Conner and Westwoods Community Church Pastor Rick Schmitz met at the dilapidated White Swan Motel, a family homeless shelter off West Colfax Avenue.

They were on a mission: Count the people sleeping outside in Lakewood.

It was part of a sweeping federal effort known as the Point in Time Count. Each year, nationwide, counties attempt to quantify how many people are living outside and in shelters.

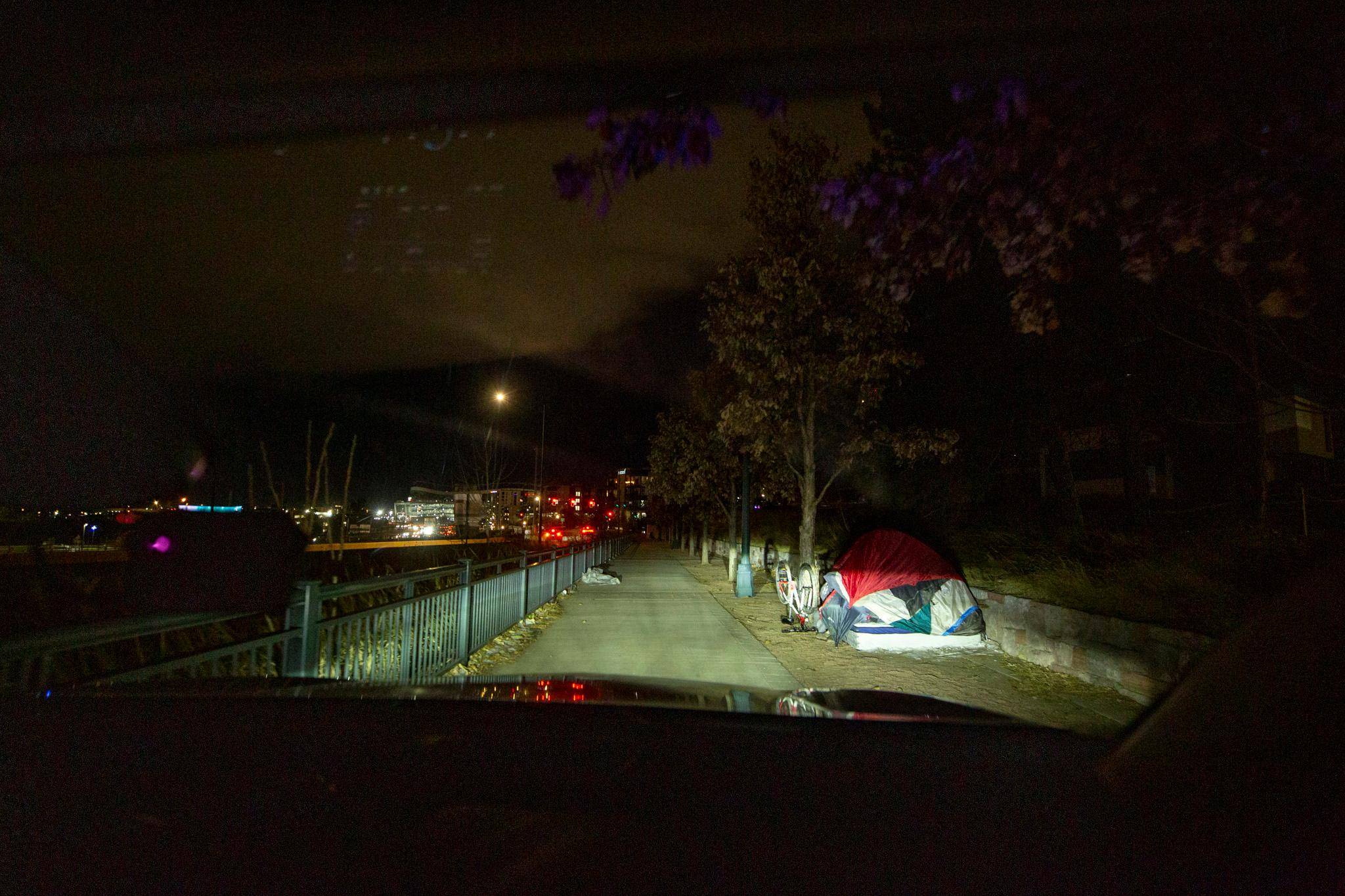

With questionnaires loaded on their phones and a map of parks and public strips where people often slept, the duo climbed into Conner’s gargantuan black truck, stuffed with winter supplies, soft drinks and snacks.

Conner warned Schmitz their shift, from 6 to 9 p.m., precedes when many people set up their camps. In the extreme cold, some would be sleeping in emergency shelters instead. They knew they would miss some people.

Still, stomping through the snow, they found men pushing shopping carts toward camping spots, others already hunkered down and some fighting the wind to put up their tents.

They counted the people and camps and convinced some to take a survey that would get at big questions: Why are you homeless? Why are you staying outside? How long have you been on the streets?

The count provides the most comprehensive one-night snapshot of homelessness in the U.S., employing thousands of people in counties across the country to count homelessness.

Yet it is imperfect at best. Denverite joined city workers in Lakewood and Denver to better understand how each community counts the people living outside and tries to interpret its findings.

The difficult work of surveying homelessness

Most everybody Schmitz and Conner would talk with were men who had been on the streets for years – in one case since the Occupy movement in 2011. All had last lived indoors in Lakewood or another suburb. Most were living outside because they did not feel comfortable or safe in the shelters.

But as they made their way through the snow, they encountered common challenges. At their first stop at Aviation Park, they approached a tent with a shopping cart out front.

“If it’s all right, I can leave you some supplies and Mountain Dew,” Conner said.

“Yeah,” a small voice answered from inside the tent.

“Can we ask you a few questions too?” Conner said. “You don't have to if you don't want to, but it helps us kind of learn more about how to be helpful.”

No answer.

“You might have heard me yesterday. I came and was asking folks if they wanted to get inside at a shelter,” he said. “Were you able to hold down OK last night? “

“Yeah,” the man mumbled in a tone that was hard to believe.

The weather had dipped into the single digits. Tents blew over. But the man had weathered it all, and was in no mood for questions — “not tonight.”

Conner left the supplies and Mountain Dew outside the tent. Schmitz did his best guesswork to answer the questions he could.

A flawed but essential source of data

It’s inherently hard to find people who have no fixed address. Some live in hiding, camped where they won’t be found.

That’s one reason Jason Johnson used to dismiss the value of the point-in-time data, knowing that it “was a gross undercount, probably by half.”

But today he is the head of the Metro Denver Homelessness Initiative, the nonprofit that conducts the survey in Denver and manages federal housing dollars.

The quality of the count varies county by county and volunteer by volunteer, he acknowledged. Some cities like Denver deploy paid city workers, while many others rely on volunteers. Nationally, different communities count at different times of day.

“It used to be that hordes of volunteers would go out and if they saw someone under a blanket or on a park bench, maybe steamed up windows in a car, they would count that individual and move along,” Johnson said.

But the strategy has improved nationally more recently, he said.

Now, volunteers ask questions of the people they encounter and learn about how homelessness works in various communities. The information is more useful than ever, as he sees it, adding up to a portrait of the many forms of homelessness.

The PIT also uses information collected by shelters, transitional housing, day centers and outreach workers.

“We pull a lot of information to get a richer head count and a more accurate head count than any community could ever do just by that visual count,” Johnson said.

MDHI plans to present the local numbers in April and the federal tally will likely come later.

The PIT can be politically charged.

In 2023, there were 1,423 people counted as unsheltered in Denver. In 2025, there were 785 people counted outside — a 45 percent reduction. Mayor Mike Johnston described it as a national record and proof that his All In Mile High homelessness strategy was working.

At his State of the City address, Johnston claimed “record reductions in homelessness,” based on the PIT’s count of unsheltered people, even as sheltered homelessness grew.

The PIT’s variability also raises questions about how much of the reduction in unsheltered homelessness can be attributed to the mayor or any other factor.

MDHI itself cautions not to extrapolate trends over time from PIT data.

“The PIT is only a snapshot of homelessness on a single night in January with numerous variables that could result in an undercount,” Jenn Myers, a spokesperson for MDHI, wrote Denverite.

Mayor Mike Johnston listens as housing advocate V Reeves speaks about the need for more family shelters, during a public meeting at the Central Park Recreation Center on Johnston's evolving solutions to homelessness. Sept. 25, 2025. Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Rae Cranmer speaks during a press conference urging Denver to fund family shelters, convened by Housekeys Action Network of Denver, before Denver City Council's public comment session on Oct. 27, 2025. Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Housekeys Action Network Denver, a homelessness advocacy group, argues that Johnston’s claim of a reduction is overblown, arguing that cold weather in 2025 artificially reduced unsheltered homelessness by pushing people inside.

“The Mayor’s office has been touting a ‘45 percent reduction in unsheltered homelessness,’ but it is clear this is false,” Housekeys Action Network Denver wrote in a statement.

The mayor’s office says they made a fair comparison, correctly pointing out that temperatures were actually lower in 2023 than in 2025, likely driving a similar or larger percentage of people into cold-weather shelters. The city did not track how many people stayed in the emergency cold-weather shelters during the 2023 PIT.

The mayor’s office stands by the quality of the data, saying it followed HUD standards that dictate how people in emergency shelters are counted. Critics say the PIT numbers should include a footnote explaining that the numbers could be affected by cold temperatures.

In Denver, some signs of a change this year:

Despite doubts about the data, some of the people conducting the survey in the city of Denver said they saw fewer people outside.

Denver Park Ranger Corey Beaton set out well before sunrise for his sixth point-in-time count. In years past, he’d expect to find a lot of tents and people sleeping rough during this exercise. This morning, though, he had different expectations.

“Gone are the days of encampments that would circle an entire city block. I think those were a temporary situation while the city built the framework that is now being shown to have success, be it transitional housing or permanent housing or more shelters. So yeah, things have gotten a lot better,” he said.

Beaton cruised by the Eddie Maestas Community Garden, across Park Avenue from the Denver Rescue Mission, where one person was lying under a blanket. Uptown’s Benedict Fountain Park was empty, as was Skyline Park.

He counted one person each at the Quality Hill pocket park in Capitol Hill, Governor’s Park and the westside’s Sunken Gardens. There was no one to count at Sonny Lawson or La Alma/Lincoln Parks, which Denver officials temporarily closed in recent years to address concerns about safety and visible poverty.

All in all, there were far fewer people outside than Beaton had encountered in the past, and he attributed that to Denver’s efforts to bring people inside and connect them with services and housing.

“It's pretty quiet today,” he said as he drove. But the final data won’t be available for months — and it will leave plenty of questions unanswered.

What does homelessness look like in your community, or your life? Share your questions and observations.

Editor’s note: This article was updated to add additional comment from MDHI and context and comment from the mayor’s office on advocates’ claims that cold weather led to a lower count of unsheltered homelessness in 2025. The count in 2023 was also conducted in cold weather. Emergency shelters were open during both years’ counts.