Colorado faced the possibility of deep budget cuts this year because the state had too much money. If that's tough to understand, you'll want to read on a bit.

It's the paradox and the intent of the Taxpayer's Bill of Rights, the state constitutional amendment passed in 1992 that seeks to prevent the growth of government. State government is almost certainly smaller than it would have been without TABOR, but it has kept growing.

Instead, TABOR's limits on taxing and spending and the way it interacts with other elements of state law have helped set the stage for a big long-term budget gap — almost $3 billion by 2030, according to the most recent estimates, with just three areas of spending, K-12 education, health care and prisons, crowding out every other need. And the proposals to shrink that gap will all need to contend with the political and legal realities created by TABOR.

A table of contents to this fairly epic explanation of a law that comes up a lot in Colorado:

- A TABOR example from this year

- The 1-minute explanation of TABOR's impacts

- So how does TABOR work?

- Enter Referendum C

- What does this mean for the average person in Colorado?

- Wait. So why is education eating up the state budget even as our spending per pupil lags?

- Where did TABOR come from?

- It took four tries to get TABOR into the constitution.

- What about cities like Denver?

- Imagine life with no TABOR (it's harder than you think)

Here's a TABOR example from this year.

TABOR sets limits on the amount of money the state can collect and spend, even when tax rates stay the same. This year, revenue from one source, the hospital provider fee, was pushing the state above the limits set by TABOR, but money from the fee couldn't be used to pay the refunds that taxpayers would be owed, so it would have to come from somewhere else.

Money from the hospital provider fee doesn't just sit there in the budget to be used for any old thing. It gets matched by federal dollars and goes back out to hospitals to pay for health care. Instead, the refund money would have come out of the general fund that's used to pay for schools, human services, courts, prisons, higher ed and other services.

The legislature ultimately passed a bipartisan $27 billion budget without TABOR refunds or deep cuts by reducing the amount of the hospital provider fee (CPR's Vic Vela has a very clear breakdown of the budget compromise here), but just about everyone thinks these issues will keep coming up.

Here's the 1-minute version of TABOR's impacts.

TABOR and its mandate to return extra revenue to taxpayers is directly responsible for about a third of the long-term budget gap, said Phyllis Resnick, lead economist with the Colorado Futures Center at Colorado State University. She and her colleagues are the authors of the Colorado Sustainability Study, which first examined the long-term budget gap in 2011 and was updated in 2013. Another update is expected by the end of 2016.

Resnick doesn't attribute the rest of the gap to TABOR but to demographic and economic changes. Sales tax captures much less economic activity than it once did because people spend more money on services that aren't taxed. As Baby Boomers age, costs for long-term care under Medicaid will go up and up. Complicated and interconnected school funding formulas mean more and more of the general fund has to go to K-12 education.

But under TABOR, changing the sales tax to include services probably would require a vote in a state where voters have approved just two new statewide taxes — in 24 years. What Resnick calls the "Gordian knot" of school finance was twisted and tied by the way TABOR interacts with other elements of state law to affect local funding for education. Health care costs could be removed from the general fund budget — that's what the hospital provider fee debate is about — but many Republicans see doing so as breaking faith with TABOR.

The short version: Just getting rid of TABOR would not solve Colorado's fiscal problems, but TABOR makes those problems much harder to fix. Unless you want to cut a lot of programs and services.

So how does TABOR work?

There are four main things that TABOR does:

- Any tax increase has to be approved by voters. This is the most well-known provision and the one that many people think of when they think of TABOR. After all, we see these tax requests on our ballots year after year.

- Regardless of how much money taxes bring in, spending cannot go up by more than inflation plus the increase in population added to the previous year's spending.

- Any revenue collected above and beyond that increase in inflation and population must be returned to taxpayers.

- TABOR puts several types of taxes off limits: state property taxes, local income taxes and real estate transfer taxes. Where they exist, they can never be raised, and where they don't exist, forget it.

Colorado voters said no again and again in the 1990s to statewide tax increases and requests for the state to keep revenue above the TABOR limit, and in the late 1990s, the legislature adopted permanent tax cuts so they wouldn't have to keep giving refunds to taxpayers. Once taxes were cut, it would require a vote of the people to restore them. If the legislature had left rates where they were, they would be worth around $650 million a year in additional revenue today, according to Natalie Mullis, chief economist for the legislature.

But the good times didn't last. When the recession of the early 2000s hit, revenues fell, and TABOR's formula that links this year's spending limit to last year's spending created a "ratchet" effect that reduced the base from which spending could grow.

Enter Referendum C.

Colorado can actually spend much more money today than it would have been able to if voters hadn't approved an important change in 2005. Referendum C suspended the TABOR spending limits for five years to allow the state to replenish its coffers after the recession. It also changed how the base is calculated to get rid of the ratchet effect.

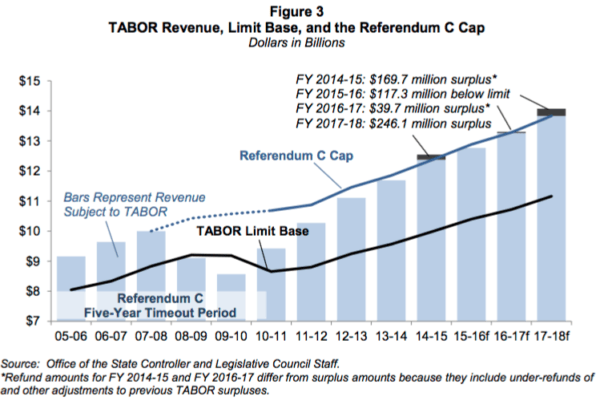

This chart, prepared by the economic section of the Colorado Legislative Council as part of their quarterly forecast, shows how dramatic the effect of Referendum C is on the money available to the state.

It's not hard to see why the libertarian Independence Institute calls Referendum C "the largest tax increase in Colorado history," though it doesn't involve an increase in tax rates, only letting the state keep the money generated by existing taxes.

And of course, it was approved by voters, as TABOR requires.

Referendum C isn't the only work-around. More and more of the state budget now lives in enterprise funds, state-run "businesses" that charge fees for service and don't get more than 10 percent of their budget from the state. These enterprises aren't subject to TABOR spending limits. Examples include higher education, the Division of Wildlife and unemployment. More than 60 percent of the state budget is exempt from TABOR limits, and lots of groups, not just Democrats, would like to see the hospital provider fee also become an enterprise fund.

However, the state is bumping up against even the higher spending limit, and the forecasts call for refunds starting in the 2017-18 fiscal year and for several years to come. Even with the hospital provider fee in the budget, the vagaries of the economic cycle could keep Colorado under the Referendum C limits in some years, Mullis said, meaning there would not be refunds. However, Resnick said the long-term trend, between the expansion of Medicaid, the aging of the Baby Boomers and the pressures on K-12 education is for costs to keep going up and push the state above its spending limit on a regular basis.

(Prisons are the third area of spending that crowds out other needs in the general fund over time, not because prison costs are growing that quickly but because the state can't reduce prison spending very much without getting slapped with lawsuits over bad conditions. The cost is determined mostly by the number of prisoners, which can go up and down in somewhat unpredictable ways, and wages for corrections officers.)

"TABOR is not really causing the structural gap, except that we’re being forced to do refunds, but the overall problem is that revenues aren’t keeping pace with costs," Resnick said. "Without a change to the revenue system, those services will go."

What does this mean for the average person in Colorado?

Well. Colorado was a relatively low-tax state before TABOR, and the per capita tax burden is slightly lower today, though we also pay more because incomes are higher.

The Tax Foundation ranked Colorado 35th in the country for tax burden for fiscal year 2012, the most recent year for which data is available. Several of the states ranked below Colorado don't have a state income tax at all; when compared to states with the normal types of taxes, we're even lower.

In 1992, the total per capita state tax burden was 10.1 percent, and in 2012, it was 8.9 percent. Incomes have risen, and in real dollars, each person in Colorado paid $2,967 to the state in 2012 compared to $2,501 in 1992.

The state has given back $3.3 billion in TABOR refunds. In a study of the impact of two decades of TABOR, the Independence Institute's Fred Holden identified $800 per person in TABOR refunds between 1992-2012 and savings of more than $6,000 per person in taxes that would have been paid if TABOR were never adopted and taxes continued to grow at the same rate as in the decade before TABOR. From the study:

"In two decades, TABOR’s restraint of government spending growth cumulatively saved each person in Colorado about $6,173.

"Suppose that taxpayers had invested their savings, earning an annual return of 2 or 3 percent? Figure 18 shows the results. An individual would have about $7,460 (2% return) or $8,229 (3% return).

"Of course for a family of four, the above figures would be multiplied by four. Cumulatively, the savings are quite large: enough to pay for several semesters of college tuition (depending on the school), or purchase of one or two good-quality used cars."

Depending on the school, indeed. The state used to pick up two-thirds of the cost of tuition at Colorado's state schools, while student tuition and fees paid the rest. That ratio is now reversed.

But yes, 20 years of TABOR-related tax savings would allow one person to make a big dent in — but not cover — one year of in-state tuition at CU-Boulder. The university put tuition and fees for the 2015-2016 school year at $11,273-$15,857.

Colorado also ranks near the bottom in per-student spending on higher ed. A 2015 study by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences showed Colorado as one of six states where per-student support for higher ed amounts to less than $4,000 a year. Tuition has increased as state funding has fallen, though this year's budget averted feared cuts. The issues facing Colorado — rising costs for K-12 education, health care and prisons — affect many states, but the challenges are greater in Colorado (more on that in the next section).

"People think it’s because, 'Oh, we have this limit,' but the reason we’re squeezing everything out of the budget is because we have to pay so much for K-12," Resnick said. "We’re getting these kids through 12th grade, but we’re not helping them with college."

But even as K-12 education takes up a larger share of the state budget, Colorado has fallen behind the rest of the country on education spending. Colorado used to be in the middle of the pack for states, but now we're toward the bottom.

Different methodologies result in different rankings. Ed Week puts us at 37th for spending and gives Colorado a D+. The state's Legislative Council staff analysis puts us at 39th for spending on education.

At the same time, Ed Week ranks Colorado 13th and gives the state a B when looking at students' overall "chance of success," a metric that looks at school performance but also demographic factors like how many children live in poverty.

And of course, these issues doesn't just affect education. Colorado hasn't raised its gas tax of 22 cents per gallon since the year before TABOR was passed. (To be fair, the feds haven't raised their gas tax of 18.4 cents since 1993. What's their excuse?) And cars today are more fuel efficient, so drivers pay less tax per mile driven at the same time that construction costs have risen.

For fiscal year 2015-16, just 3.9 percent of the state's total expenditures went to transportation, the lowest rate of any state in the country, according to information compiled by the National Association of State Budget Officers. The national average is 7.7 percent.

Colorado adopted FASTER fees on motor vehicle registration, rental cars and overweight vehicles in 2009 to provide more transportation funding without going to voters. Another bill from that same year, during the height of the Great Recession, called for 2 percent of the general fund to be put into transportation for five years, with transfers to start when revenues had sufficiently recovered. That started in the 2014-15 fiscal year. However, if TABOR refunds kick in, the transfer from the general fund to transportation goes down or is even eliminated. A bill this year guaranteed that funding for two fiscal years, regardless of what happens with a revenue surplus or TABOR refund. That means roads will get money they need, but any refunds would have to come out of other programs.

Why is education eating up the state budget even as our spending per pupil lags?

This is complicated, but it has to do with how TABOR interacts with the Gallagher Amendment, the School Finance Act of 1994, Amendment 23, the vagaries of the real estate market and the Great Recession.

The Gallagher Amendment pre-dates TABOR and says that residential property shouldn't provide more than 45 percent of the property tax revenue for schools. It didn't really restrict revenue to school districts on its own. But after TABOR, when mill levies went down to keep that ratio in place vis a vis commercial properties, they couldn't go up again without a vote. Similarly, when property values went up, districts had to decrease their mill levies to not end up with extra money. When property values went down, they couldn't let the levies float back up without a vote.

The School Finance Act sets a per-pupil base funding amount. After school districts provide their share, the state fills in the rest. And then Amendment 23, approved by voters in 2000, required that K-12 education funding grow at a rate greater than inflation without providing additional money to the state.

During the Great Recession when revenue was lower, the state dealt with the pressure Amendment 23 put on the budget by increasing only the "base" amount it paid per-pupil and applying a formula called the "negative factor" to reduce total payments to districts. It was just this year that per-pupil spending returned to 2009 levels.

Local taxes used to make up 65 percent of education funding, with the state providing the rest. That ratio is now reversed. At the same time, an analysis from the Colorado Futures Center found that many Coloradans pay higher local property taxes for schools now than they would have without TABOR, property tax savings are concentrated among higher-income households and wealthier districts are being subsidized by the state at the expense of poorer ones.

Untangling all of this and letting local districts cover more of their costs with property taxes would free up a lot of money in the state general fund for other things, Resnick said.

Matthew Mitchell, director of the Project for the Study of American Capitalism at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, has studied the effects of tax and expenditure limits and sees them as an important brake on the tendency of government to be more responsive to groups that want to spend more.

At the same time, if states are required to simultaneously limit spending and spend more, well, that's a problem.

"Having two provisions of the constitution that are mathmetically on a collision course with each other is not going to lead to a good outcome," he said. "People are going to disagree about which provision should go, but it’s not a sustainable pattern."

Where did TABOR come from?

Doug Bruce didn't invent the idea of a Taxpayer's Bill of Rights — he moved to Colorado from California the year the first attempt lost at the ballot — but it was his persistence that got it enacted.

Bruce spent less than a year in the state House, during which time he was formally censured for kicking a photographer for the Rocky Mountain News and was removed from the State Veterans and Military Affairs Committee because he refused to support a resolution honoring veterans. He lost his primary and returned to private life.

The man who did more than perhaps any other individual to shape modern Colorado is in prison now for violating the terms of his probation on tax evasion charges.

Definitely go read the Colorado Springs Gazette's retrospective on Bruce, "A Greek Tragedy":

"As with every tragedy, this protagonist is flawed. Bruce's temperament angers even those who share his values. He's been called a jackass, a slumlord, a crackpot and a sociopath. And those are only the printable names."

It took four tries to get TABOR into the constitution.

Colorado voters turned down the first constitutional amendment that would have required a vote on new taxes by 62.5 percent in 1986. Two years later, 57.8 percent of voters rejected an amendment that had all the basic elements, the vote requirement, the restriction on spending, the limit on types of taxes. But by 1990, only 51 percent of Colorado voters said no.

In 1992, backers got the victory they had been waiting for, with 53 percent of Colorado voters saying yes to the toughest restrictions on taxing and spending anywhere in the country.

It was the same year anti-gay rights Amendment 2 passed, with the same margin of support.

From that point on, Colorado voters said no again and again to tax increase requests. No to a tax increase on tourism-related purchases in 1993, no to an increase in the tobacco tax in 1994, no to an increase for transportation needs in 1997 and no to a request in 1998 to keep excess revenue for five years and spend it on school construction and transportation, no to a request in 2000 to keep excess revenue and use it for grants to help schools teach math and science better.

The answer was no again in 2008 to a request to raise taxes on mineral extraction and use the money for transportation needs, no to a request to raise the sales tax to pay for long-term care for people with disabilities and no to a request to let the state keep excess revenue and spend it on education.

Voters said no again to tax increases to pay for education in 2011 and in 2013.

But voters have also said no to attempts to limit taxes even further. Bruce pushed a constitutional amendment in 2000 that would have required local governments to reduce each tax bill by $25 in the first year, then $50 in the year after, then $75 and so on. This time, 66 percent of voters rejected it.

And in 2010 voters rejected a trio of constitutional amendments that would have cut taxes even further. Doug Bruce was behind these measures too though he tried to obscure the connection. (Proponents claimed they did not know who was behind the email address of [email protected] that gave them direction.)

Initiatives 60, 61 and 101 would have allowed voters to place initiatives on the ballot reducing taxes, would have prohibited state government from borrowing any money and required voter approval for local borrowing and would have phased out most vehicle taxes.

What about cities like Denver?

Asking voters for permission to keep excess revenue above the TABOR limit is known as de-brucing.

Cities have been remarkably successful in de-brucing, with Colorado's 272 municipalities having received permission to keep excess revenue 476 times since 1992 and being turned down by voters just 74 times, according to information collected by the Colorado Municipal League, a success rate of 86.5 percent.

(There are more requests than there are cities and towns because some of them are temporary.)

Even tax increases fare better at the local level, with 503 increases passing and 345 failing.

"It still has an effect on government, but I think what it says is that voters support municipal services and want to make sure they are adequately funded," said Mark Radtke, a research analyst with the municipal league. "I point to the fact that residents are usually much more aware of projects that might be connected to the tax increase. It might be improving an intersection they drive through all the time, and they know if it’s a mess. Or if the library is falling down, they know. It’s easier for them to visualize."

Denver completely de-bruced in 2012. Its voters have also approved many — though not all — tax increases, willingly taking on debt and taxes for the football stadium, the Colorado Convention Center and improvements at Denver Art Museum, Denver Health and the Denver Zoo, as well as to provide funding for preschool subsidies and services for people with disabilities.

And perhaps most significantly, metro area voters approved the 0.4 percent sales tax increase in 2004 that has paid for the massive expansion of the Regional Transportation District's light rail system.

Imagine there's no TABOR. It's ... it's actually kind of hard to do.

Colorado would almost certainly look different today if TABOR had never passed, but it's hard to say exactly how. Each year, a legislature composed of dozens of individuals meets and makes decisions about revenue and spending, and it's hard to say what taxes they would or wouldn't have adopted and how they would have chosen to spend them, how voters might have reacted to those choices and what adjustments future legislatures would make.

But TABOR doesn't seem to be going anywhere. Supporting it is an article of faith among Republicans. A group formed in 2016 to get a measure on the ballot that would have let the state keep excess revenue for the next 10 years and spend it on education, transportation, mental health and senior services. In each press release, though, supporters make sure to say it wouldn't change TABOR and in fact does what TABOR intends by giving voters a choice. A choice to correct a problem created by "a 24-year-old law." And then they gave up the effort, saying they feared it would be a distraction in a crucial election year.

Assistant Editor Erica Meltzer can be reached via email at [email protected] or twitter.com/meltzere.

Subscribe to Denverite’s newsletter here.