Johnathan Barker was facing 32 years in prison when he finally broke his addiction to drugs and alcohol.

He was passed out in his car, outside the dangerous Evans Avenue apartment building where he lived, when police officers found him and arrested him in 2021. He was charged with DUI and drug possession, which compounded on illegal firearm charges from earlier that year.

Barker was sent to Denver’s sobriety court, where he was told he could avoid decades in prison if he stayed clean, got a job and secured a driver’s license. He was scared, and he wasn’t sure he could do it.

But he met someone who offered a lifeline, who had overcome her own struggles and could help him through the process.

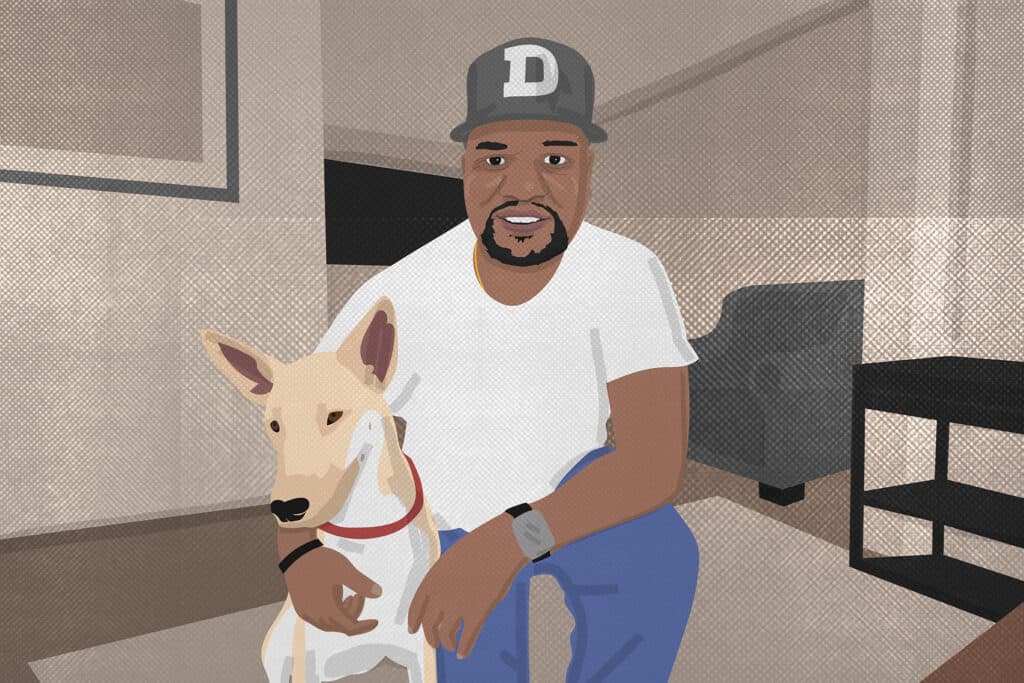

“She was just bold. ‘Come with me. I got you.’ And I'm like, OK,’” he said, shaking his head during a recent interview in his Athmar Park apartment. “It seemed like the gate to heaven opened up. This person was willing to speak on my behalf, help me advocate for myself.”

The woman helped him get into a sober living home, then deal with an open warrant, then go to the DMV. With help, he made it through three years of check-ins and graduated from the court’s requirements.

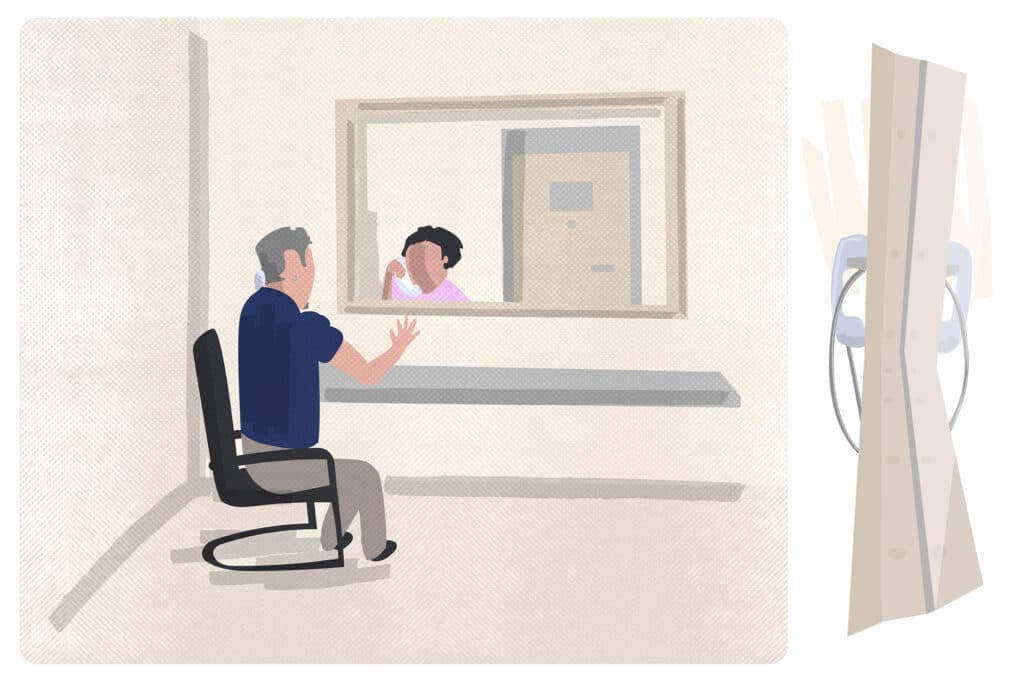

Cameras are not allowed in Denver courtrooms. Instead, Denverite journalist Kevin J. Beaty sketched scenes he witnessed and turned them into digital illustrations. He applied the same style to scenes captured outside the courtroom, too.

That success is exactly what Denver County Court’s Forensic Peer Navigator program hopes to achieve. It employs people, like the woman who helped Barker, who have lived experience in homelessness and addiction and who are uniquely qualified to guide others out of their own destructive cycles.

It’s part of a growing national trend to provide support in the justice system for people struggling with substance use and poverty. Denverite spent a recent morning observing the team, to see how it’s working to make local courts places of true rehabilitation for people who might otherwise be stuck in cycles of arrest and imprisonment.

The court’s navigators watch hearings every day, intercepting people while they’re stuck in the system.

On a recent morning, Denver County Court navigator Mark Donaldson sat in the mostly empty pews of a courtroom in Denver’s downtown jail. Large glass windows lined one side of the room, revealing people in green, yellow and pink scrubs sitting on the other side waiting to face allegations against them.

Magistrate AnnMarie Spain called up the accused, one at a time, to a microphone in the holding cell. Many were there for crimes related to substance abuse, like DUIs and possession. Some had failed to appear on other charges and were brought in on warrants; others had long histories of arrest.

Donaldson watched as a woman in pink approached the glass. She had been arrested for drug crimes and agreed to a plea deal with the court; if she followed the program, the case would be dropped and her charges sealed.

“What’s your understanding of this plea?” Spain asked.

“I have 56 days to set six goals and to achieve them,” the woman said. “If I don’t achieve those goals within 56 days, I will have to accept 10 days in jail.”

Then, she added: “I’m ready to meet with an advisor.”

That was Donaldson’s cue. Not many people agreed to meet with him, but here was someone who was motivated to listen.

He met her in a room next to the court, bisected by another pane of glass. They spoke through a phone bolted to the wall.

“My name is Mark and I’m a peer support specialist. What that means is I have lived experience. I had a drug charge, I got a DUI, and I don’t do that anymore,” he told her.

Yes, she said, she had a drug problem that she wanted to kick, but whether she wanted to cut down or quit altogether didn’t matter to him. He would help her regardless.

“I just want to help you with your path,” he said.

She asked, what about help finding housing? That was harder, Donaldson said. She should go to the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless, get a case manager and wait on a lottery for a voucher.

“It’s not a fast or easy process, but it does work,” he said.

This was a good meeting, Donaldson told us. They would try to meet up once she was released.

“I love highly motivated people,” he said as he left the tiny room.

Navigators can’t solve people’s problems, but their presence makes a difference.

That was the case for Barker, who said he couldn’t imagine a way out of his drug use when he was connected with a peer navigator in 2021.

He was afraid to return to his Evans Avenue apartment. There were people there who might hurt him there, which is why he had the illegal gun. But he was also afraid to talk to people who said they wanted to help. Judges — really, anyone in the court — seemed untrustworthy.

“I was so scared of the legal system,” he said. “You're there by yourself, and there's a lot of [stuff] that you don't understand, the language or the workings of court. It becomes this scary … beast.”

The navigator he met, Sarah, changed his perspective once she won him over.

He was ready to flee when she took him to address a warrant in Jefferson County. But she talked to the clerk and got a hearing set for him, no problem, as he stood nervously by the door.

“She helped me through that,” he remembered. “I trusted her. And trusting her, I started trusting my [parole officer]. I started trusting the judge, which helped me out tremendously. All these times in my recovery, it was trusting someone else — where I'm from, the streets, you don't trust nobody.”

Joseph Ellis, manager of Denver County Court’s navigation program, said the need for trust is something he understands deeply. The U.S. Army veteran fell into addiction after he left the military in 2000. It took him a half-dozen tries to finally get clean.

“When I talk to somebody who's struggling, I'm talking to myself, too, because I've been there,” he said. “We're the ones that are going to walk beside them all the way through it and make sure the dots get connected.”

Ellis said his program has connected with over 2,800 people since it began in 2020.

About 1,600 of those meetings happened in 2024 alone. According to Denver County Court’s 2024 annual report, Ellis’ team made 3,057 referrals to over 1,300 providers, most to the Second Chance Center and the Denver Aid Center (which Denver officials announced will soon close).

Ellis said members of his team, usually five or six people, each manage 50 to 60 active cases at once.

Assessing the program’s success is tricky. According to Denver County Court’s 2024 annual report, 39 percent of people who worked with a navigator were arrested again within one year. For context, Denver Sobriety Court, which handles cases related to substance abuse, had an overall one-year recidivism rate of 9 percent in 2024.

But Ellis said his team intentionally works with people stuck in cycles of incarceration, who are more likely to reoffend. They serve people without anyone else to rely on, a “relational poverty” that underpins chronic homelessness and addiction. Many of his clients, he said, have experience with both.

The program has been funded by grants from Caring for Denver, totaling about $1.4 million over six years for staffing and support for clients, such as cell phones, food and transportation.

“We could help more,” Ellis said. “The need’s there, and it's not getting any smaller.”

Denver’s Office of the Municipal Public Defender also created a peer navigator program in the last few years. Colette Tvedt, who leads the office, said the programs are proof Denver’s courts are chipping away at the city’s systemic problems.

“Probably 80 percent of our clients have behavioral health, substance misuse, definitely trauma — and many have housing instability. So these are people that are really, really the most vulnerable,” she told Denverite. “I've been involved in the criminal legal system for 30 years, and it is a game changer, having peer support specialists.”

And as people accept their help, and turn corners in their lives, these projects are creating an army of people who might help someone else. Embedded in a lot of rehabilitation programs is the idea that helping others is crucial to maintaining one’s own sobriety.

That was true for Johnathan Barker, who’s celebrating three years sober in 2025. He was certified to do peer support work in the time since his last arrest and currently works with people still wrestling with addiction. He’s hoping, one day, to join Ellis’ team and give back where he found his own salvation.

“I love the recovery community. I love working with these guys, because it just reminds me of where I was three years ago and why I don't ever want to go back to. That world sucks,” he said. “Once you feel like you are connected with something, you don't want to let it go.”