Here's why Colorado Democrats and Republicans couldn't get in line for the convention -- but might in November.

In Cleveland, Colorado delegates walked out of the Republican National Convention in support of a rules change that would have opened the way to challenge Donald Trump’s nomination.

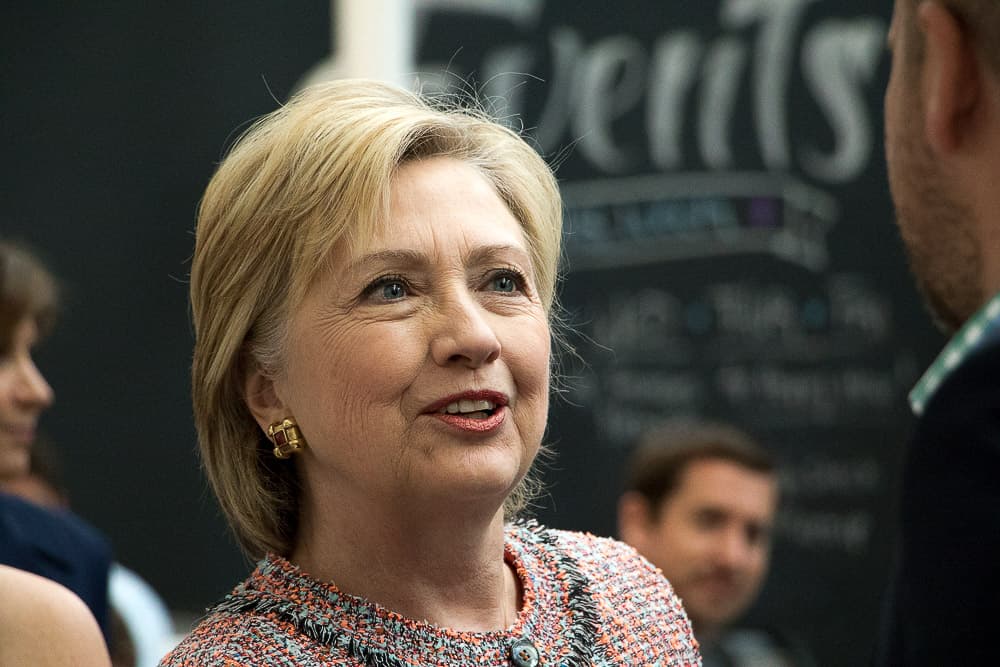

In Philadelphia, Colorado delegates walked out after Hillary Clinton was nominated and held anti-Clinton signs and wore glow-in the-dark Sanders T-shirts even as Clinton made her historic acceptance speech at the conclusion of a convention that took pains to bring Sanders supporters back into the fold.

This raises a question: Why Colorado? Why have Colorado activists been at the center of opposition to the candidates chosen by each of their respective parties?

The political scientists I spoke to hesitated to draw big conclusions, but there are a few things that we can say broadly about Colorado. There are a larger number of unaffiliated voters here than in most states. Ross Perot did really well here, winning 23 percent of the vote in 1992 compared to 18 percent nationally. Colorado is a swing state that swings harder than the country as a whole. The caucus process tends to favor the left and right flanks of each party.

But events this year on the Republican and Democratic sides were pretty different.

A Republican rules change may have been the reason Colorado sent anti-Trump delegates to Cleveland.

The Republicans canceled their presidential preference caucus, which would have highlighted the choice of rank-and-file party members. There’s no way to know in retrospect what they would have done, but there’s a decent chance they would have chosen Trump.

“Given Trump’s surprise popularity and that it was a day when Massachusetts Republicans were voting for Trump, I have to think it would have been Trump for Colorado,” said Robert Loevy, a professor emeritus of political scientist at Colorado College.

So, if average Republican voters had had a say back in March, Colorado’s delegation might have been more in line with the majority on the convention floor in Cleveland.

Instead, the Republicans selected delegates for the convention in a way that favored party activists and insiders who were almost uniformly opposed to Trump. Many people who were there dispute the notion that the process was “rigged,” as Trump has claimed. Cruz supporters were a lot more organized and understood the process better.

Nonetheless, “that really made the Republican delegation to the convention to be complete mavericks,” Loevy said.

Mavericks but establishment mavericks of a sort only this bizarre election cycle would make possible.

The issue that prompted the walk-out of Republican delegates was the lack of a roll-call vote on a rules change that would have allowed delegates to vote their conscience, rather than be bound to the candidate who prevailed in their state caucus or primary.

Republican leaders wanted to avoid that because it would have showed broader opposition to Trump than they wanted to see aired on national television. State Republican Chairman Steve House didn’t joint the walk-out but he defended his delegation and criticized the premature closure of debate.

“I think debate creates unity, not cutting off debate before it’s complete,” he told the Denver Post from the convention earlier this month. “Unity doesn’t happen because you stop someone from talking. It happens because you’ve come to some level of agreement about what’s best. I don’t think we are all the way there yet, either.”

Nonetheless, when Ted Cruz gave his highly critical speech at the RNC, it was Cruz who was booed from the floor, not Trump. And when Trump came to Colorado Friday, he hailed that as the moment the party came together and bashed the media for focusing on Cruz' dissent and not the party's unity.

On the Democratic side, Clinton had strong establishment support within Colorado.

She’s been backed all along by Gov. John Hickenlooper and Sen. Michael Bennet. Colorado’s superdelegates went for Clinton, even though Sanders had a majority of the delegates chosen by voters at caucuses. (Bennet was a superdelegate, but he missed the floor vote, prompting mockery from Republicans. His staff said it was just a scheduling matter.)

And just to be clear here, I am talking only about Colorado. Clinton won a majority of delegates nationwide, even when the superdelegates are excluded, and that’s why she’s the nominee, not Sanders.

Loevy said it’s a “cliché” in Colorado that the caucus system favors people who are more ideological on both sides. For the Democrats this year, that meant Sanders supporters easily prevailed.

“The people who tend to turn out and vote are the very liberal party activists with an agenda, usually a very liberal agenda,” he said.

At the same time, Seth Masket, a political science professor at the University of Denver, said Colorado’s system, when compared with other states, makes it easier for delegates who are political newcomers without established party connections to be chosen to represent the state at the convention.

“Really anyone can show up at these (caucuses) and with enough effort and not a lot of money, break in as a delegate,” he said. “Judging from how we've seen these things go in the past, there were Clinton supporters in ‘08 who were very upset with the party and threatening to not support Obama but ultimately they did.

“Today’s Sanders supporters are not really the same sort of people as the ‘08 Clinton supporters. They have less experience in the party. They have less loyalty.”

Raffi Mercuri, a 25-year-old Sanders delegate from Boulder, moved to Colorado three years ago for grad school. He studied education, but now he’s committed to working in politics.

“Colorado is really ... I don't know what to make of it politically,” he said. “It's a very idealistic state with this rugged individualist streak. Colorado is very attractive to people who embody certain ideals on either the conservative or liberal side.”

On the Democratic side, Mercuri called the state a “bastion of reformist neoliberalism and also a bastion of socialism.”

There are a lot of college-educated, liberal young people moving to the state -- just the sort of people who went hard for Sanders -- combined with older hippies (for lack of a better catch-all phrase) who have never been happy with the more pro-business side of the Democratic Party, Mercuri said.

In Philadelphia, the delegation “went through a transformative process,” Mercuri said. And despite careful negotiations and state Rep. Joe Salazar’s decision to back Clinton, there were delegates who remained steadfast in their opposition to the nominee.

“We had to crack down,” Mercuri said. “We had a few people who were very passionate, and I want to give credit to (state party chairman) Rick Palacio, who defended them.”

Mercuri said the Colorado delegation did not boo or heckle during Clinton’s speech as delegates from some other states did. (California seems to have been the most vocal; Mercuri said their sheer numbers made them the most noticeable.) But some members did hold up Hillary signs with letters blacked out to spell “liar.”

“They were being disruptive. They were being rude. I didn't agree with it,” he said. “But they were there to send a message and to do what they thought they were elected to do.”

Politico reported that some Sanders supporters felt the senator’s representatives didn’t do enough to prepare delegates for the fact that they had already lost. Sanders was focused on getting concessions in the party platform on issues important to progressive voters and on securing the roll call vote that would allow everyone to have their say. He knew there was no mathematical way to get the nomination.

But not everyone understood that.

“There was an unrealistic expectation on some people’s parts that the math could be changed and that somehow some type of miracle was possible,” Vermont state Rep. Diane Lanpher, a Sanders delegate, told Politico. “This is new for them.”

What does this mean going forward?

None of the political scientists I spoke to thought a third-party candidate would have a showing similar to Perot’s in 1992.

Loevy noted that Perot was able to use his own fortune to get his message across, starting in the primary season and continuing through that summer. The Green Party's Jill Stein and Gary Johnson, a former Republican governor of New Mexico running as a Libertarian, are both vying for disaffected voters, but they don't have the money or the profile that Perot did.

Mercuri is voting for Clinton while planning to keep working for progressive issues and candidates at the local level. He has no interest in going Green.

“Jill Stein has coopted this movement for Bernie and it’s disgusting,” he said. “She made this convenient appearance at the convention, but she is not a part of this movement and didn't put in the work.

“She’s done nothing to achieve things,” he added. “At least I can say that Hillary Clinton has tried to get things done. Jill Stein is throwing rocks form the sidewalk. At least Gary Johnson has been a governor.”