Hundreds of numbered plastic bags, containing thousands of pieces of gold, silver, copper or costume jewelry sit behind streaky glass display cases. Under the babble of an auctioneer drift the soft murmurs of bidders hoping to examine the vast selection of precious, semi-precious and entirely worthless jewelry.

The twenty or so people in attendance had been waiting about two years for this auction. And intensive preparation by the city of Denver and the auction houses it works with go into each and every one.

The make and model of the people filling the auction house at 1501 W. Wesley Ave. in southeast Denver earlier this month varied about as much as those of the jewelry. Some came for business, others for pleasure. Some purchased expertly, in immense quantities, while others simply bought what struck their fancy. And many seemed to know each other.

Repeat encounters at cluttered auction houses had made some allies, if not friends — all united, at least, by the thrill of the auction.

On a surface level, the operations of a government auction seem quite complicated -- and they are.

It starts with the jewelry.

The city of Denver can only host auctions if they have enough inventory. And inventory comes from jewelry lost in airports, art venues, theaters and arenas, according to Kris Deutemeyer who runs the city's surplus property sales.

Once the jewelry has been collected, Deutemeyer brings in an appraiser to determine the value of the finds, a few months in advance of the auction. The jewelry is then sorted and shipped to the auction house.

A lot of recovered goods are sold through online auctions -- the city partners with www.govdeals.com for this -- but the amount of work that would go into listing jewelry online would be overwhelming.

Why do jewelry auctions need to be in person?

"The volume, the clientele, the amount of work it would take to accurately describe something we put online," Deutemeyer said. "I prefer the buyer actually see the item."

And see the items, they do.

One day in advance of the long-awaited auction, attendees were invited to come down to the family-owned auction house Dickensheet and Associates for about five hours to examine the bagged jewelry. And then, again, the day of the auction, one hour before bidding started.

Having only been given very vague descriptions of the jewelry in advance of the event, any expert bidder knows the importance of auction previews.

Peter, who asked that only his first name be used, runs a jewelry and antiques shop in Wheat Ridge, an online sales business and an antiques kiosk in a mall. He has been attending the city's jewelry auction for about 15 years, and uses what he purchases to supplement his businesses.

"I look at every lot, every single lot that they have, and I search for little treasures," he said. Peter said he spent a total of 30 hours preparing for the 2016 auction, and he usually spends about $20,000.

According to Peter, the resale money he earns from the most valuable item in a bag of about 150 pieces of jewelry can make up for the cost of the entire bag at auction. He then passes along savings to his customers.

There were many at the auction who, like Peter, seemed to be stocking up for business. But not every attendee was an expert.

Sandi Gargaro of Grand Junction has been attending city auctions for about 10 years. She said she typically attends city auctions of various sorts about every other month, for fun and to find her favorite jewelry.

"I'm crazy about sapphires," she said. "I don't know why I have so many or will get so many more."

November's jewelry auction was the first hosted by Dickensheet and Associates.

The city of Denver dispenses contracts to auctioneers once every five years. The previous contract expired this past summer. When it went out to bid, Dickensheet secured the contract.

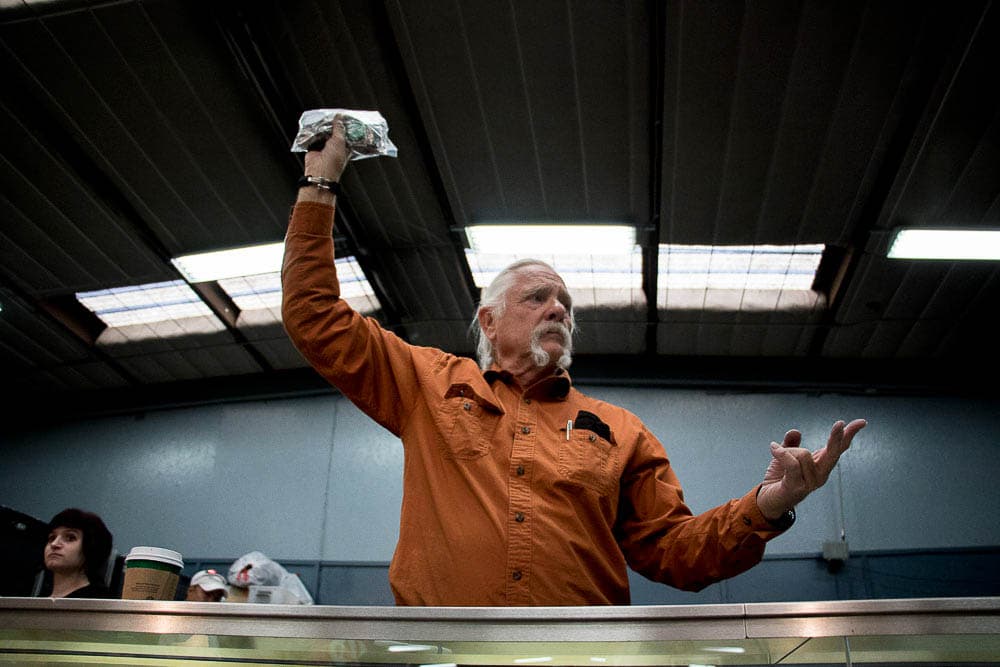

The auctioneers play a key role in ensuring the city -- and the auction house, by extension -- makes money. The constant hectic babble of the auctioneer is enough to confuse first-timers, but it keeps the hours (six of them, in all) passing, the pace fast and the jewelry selling.

In exchange for its services, Dickensheet and Associates make an 8 percent commission from the auction's total sales, as paid by the city, Deutemeyer said.

But not all are fans of the new auction house.

Peter said he felt the new auction house employed techniques that would make him reconsider attending again in the future, even after 15 years.

"Normally you can only examine the jewelry before," he said. "This one surprised me because people were standing there looking at bags and bidding on them."

He said that kind of tactic pushes prices through the roof. He said he left the auction with about 12 bags of jewelry, compared to the 30 he typically buys.

"I am seriously contemplating not going next year, because I thought it was wrong," he said.

We tried to ask Dickensheet and Associates about this practice, but they weren't particularly cooperative.

Each auction, about $100,000 worth of jewelry is sold. During the following year and a half to two years, inventory is collected until there is enough to do it all over again.

Multimedia business & healthcare reporter Chloe Aiello can be reached via email at [email protected] or twitter.com/chlobo_ilo.

Subscribe to Denverite’s newsletter here.