If you’ve ever spent time on Colfax Avenue, it’s not particularly hard to imagine the Denver of the 1930s, ‘40s or ‘50s. From one end of the city to the other, the corridor is lined with vestiges of a time when it was “the Gateway to the Rockies,” and when the best way for the motels and restaurants that lined the street to attract passing travelers was with a flashy neon sign.

Some of those old signs remain, but along with other neon signs around the city, they’re disappearing.

Four years ago, Corky Scholl created Save the Signs, a movement to do precisely what its name calls for. For about five years, he had watched and felt powerless as Denver’s neon signs disappeared.

“The straw that really broke the camel’s back was the Mozart Lounge sign,” he said. “Somebody bought it and changed the name to Aqua Lounge and painted over it. It really kind of made me sad to see that classic mid-century sign disappear like that. The day I noticed that was the day I started Save the Signs.”

And nearly four years to the day, that sign is almost ready for its return thanks to the efforts of Save the Signs and Seth Totten, who’s been bending neon since around 1990 and has owned Acme Neon Signs in the Cole neighborhood for about 11 years.

Inside the largely windowless workshop, Totten works alone under the glow of a few overhead lights and big old neon signs. It’s a dying trade, he says, one that is less and less in demand and that requires four to five years of apprenticeship to achieve proficiency. No one has ever called him looking for a job. So without the help of employees, he works at restoring the Mozart Lounge sign -- “quite a challenging one, it was pretty messed up” -- and just about any other neon he can get his hands on.

“I'm quite obsessed with saving it. I've bought out almost every old-timer within 100 miles,” Totten said. “I have done a lot of restorations for not a lot of money because I know that if I don't do that, they're not going to save it … I'll go to any length to save one of them, especially if it's headed to the dumpster.”

Inside the workshop sits the enormous Sky Line sign, which he got by trading the owner for a new sign. Out back there’s a shipping container full of signs.

And around Denver, his work remains illuminated. You can see it burning outside the A&D Motel, El Chapultepec, 20th Street Cafe, the Continental Room, Lion’s lair, VFW Post No. 1 and more.

Totten isn’t completely alone as a neon bender in this city, though. Across town in Lincoln Park, Glen Weseloh carries on the family business, Morry’s Neon Signs. Weseloh and Totten say their businesses are the only two large neon workshops left in Denver.

Morry’s Neon Signs has been in its current space for 25 years. Before that, they were working in the backs of sign shops. Weseloh’s father, Morry Weseloh, joined the electrical union after World War II. Even after the union told him he could not keep working and receiving benefits, he kept working on neon anyway. You can still see his work outside Union Station and at the former Wonder Bread bakery, among other places.

Glen Weseloh learned his father’s trade and his passion for it. Taking up the family businesses when he was gone was only natural.

“It just gets in your blood,” he said.

He employs three master benders, and though the bread and butter of their business is wholesale, he’s as determined as Totten to save the signs.

He took in the first half of the old Lancer Lounge sign from what’s now Vesper Lounge (the bar kept the “Lounge” half) because he knew it would be thrown away otherwise. It sits in the workshop among stacks of others saved from the dumpster. He also restored the neon sign for the beloved 715 Club in Five Points and does restoration work for places as far away as Wyoming and Nebraska.

Scholl himself has six rescued signs that he hopes to one day display publicly, possibly in a sign museum. Among them are the sign from the Crazy Horse Bar, which he says is ready to display right now. The other five still need to be restored, work that will cost thousands of dollars. They include the marquee from Salida’s Unique Theater, which someone donated, the Oak Alley Inn sign that once lived on South Pearl Street, a sign from iconic Colorado Boulevard gas station Bob’s Place, a sign from the mid-century Harvard Market that once sat at South University Boulevard and Harvard Avenue, and a Hi Ho Service sign.

In lieu of a neon sign museum, Scholl is hoping to find venues that can display the signs. He says he’s been in talks with the new Stanley Marketplace as a possible home for his old signs.

Ideally, though, none of this would be necessary.

“That’s the goal 100 percent, is to not ever have to have a sign museum,” Scholl said. “The reality is they do get taken down. We do try to work with people or business owners just to let them know the value of their signs and just to raise awareness of the public in general -- these are really cool and you’re better off saving them than destroying them.”

Save the Signs has organized fundraisers to keep the neons at the Oriental Theater and El Chapultepec. They’ve also been working with the new owner of the Pig ‘N’ Whistle property on West Colfax, where the sign is rusting out. The current owner is running a marijuana business there, but Scholl says he’s expressed interest in preserving the sign.

Asked why so many people discard old neon signs -- why they’re unwilling to preserve them -- all three men seem somewhat at a loss. Each of them said it’s a myth that it’s expensive and energy inefficient to maintain a neon sign. When they’re built well, they should work for decades with only minor maintenance that Weseloh says costs an average of $200 a year.

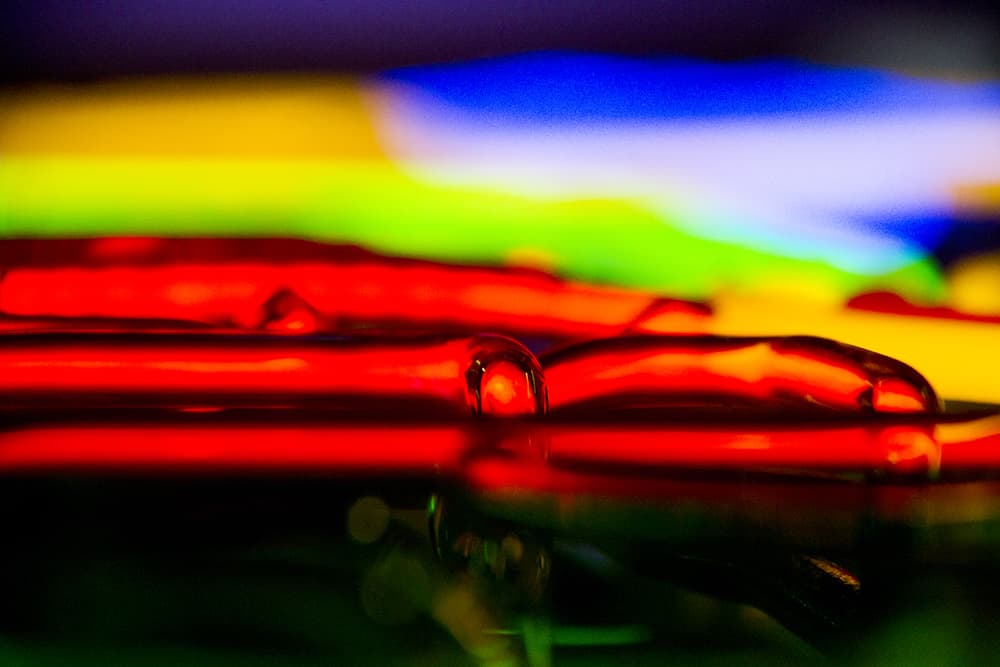

As Weseloh explained it, neon signs are created by coating the glass in phosphors in a powder-like form, filling the tube with neon gas and installing electrodes at the end of each tube. When a current is sent through the tube, the energy ignites the neon gas, which in turn energizes the phosphors. The number of colors those phosphors can create is in the hundreds.

“People will call the wrong sign company sometimes. Most sign companies will tell them, ‘Get rid of the neon, switch to LED.’” Scholl said. “The LED technology is maybe a little more energy efficient, but neon is actually an energy efficient light source … and it’s built to last. The craftsman who are still working on it, like Seth and Glen, they’re not part of a grand obsolescence conspiracy.”

He said there can be issues with the glass tubes being susceptible to breaking in hail storms, but well-made signs are known to last through that sort of thing, too.

“Neon’s gotten a bad rap over the years ... Saying it doesn't last and is not energy efficient, which is a bunch of crap,” Totten said. “I've personally pulled working neon off of a 60-year-old sign. It lasts if it's done right.”

And there are obstacles to installing new neon signs, too. Totten says Denver sign codes put strict regulations on signs that blink or protrude from a building. He also says that companies have discontinued certain colors and stopped making the equipment. He generally has to order the equipment and parts by mail.

He did say that he’s been getting more requests for new signs lately, though.

It's not just three men who care about neon. The Save the Signs Facebook page has more than 8,600 likes, and the more people who care, the better.

“You just have to really be vigilant because a sign can disappear overnight,” Scholl said. “Things are happening so fast in this city, the signs can just disappear. Here one day and gone the next … The more eyes on the street there are, the better.”

So preservation really comes down to this: If you see something, say something.