Even the freedom of the open road wasn't available to all in the Jim Crow era of the United States.

Though writer George Shyler encouraged African-Americans to buy cars in 1930 "to be free of discomfort, discrimination, segregation and insult," not much could be guaranteed once the car was stopped.

African-American tourists would drive all night, pack picnics or even carry portable toilets in the trunks of their cars to avoid possibly dangerous situations.

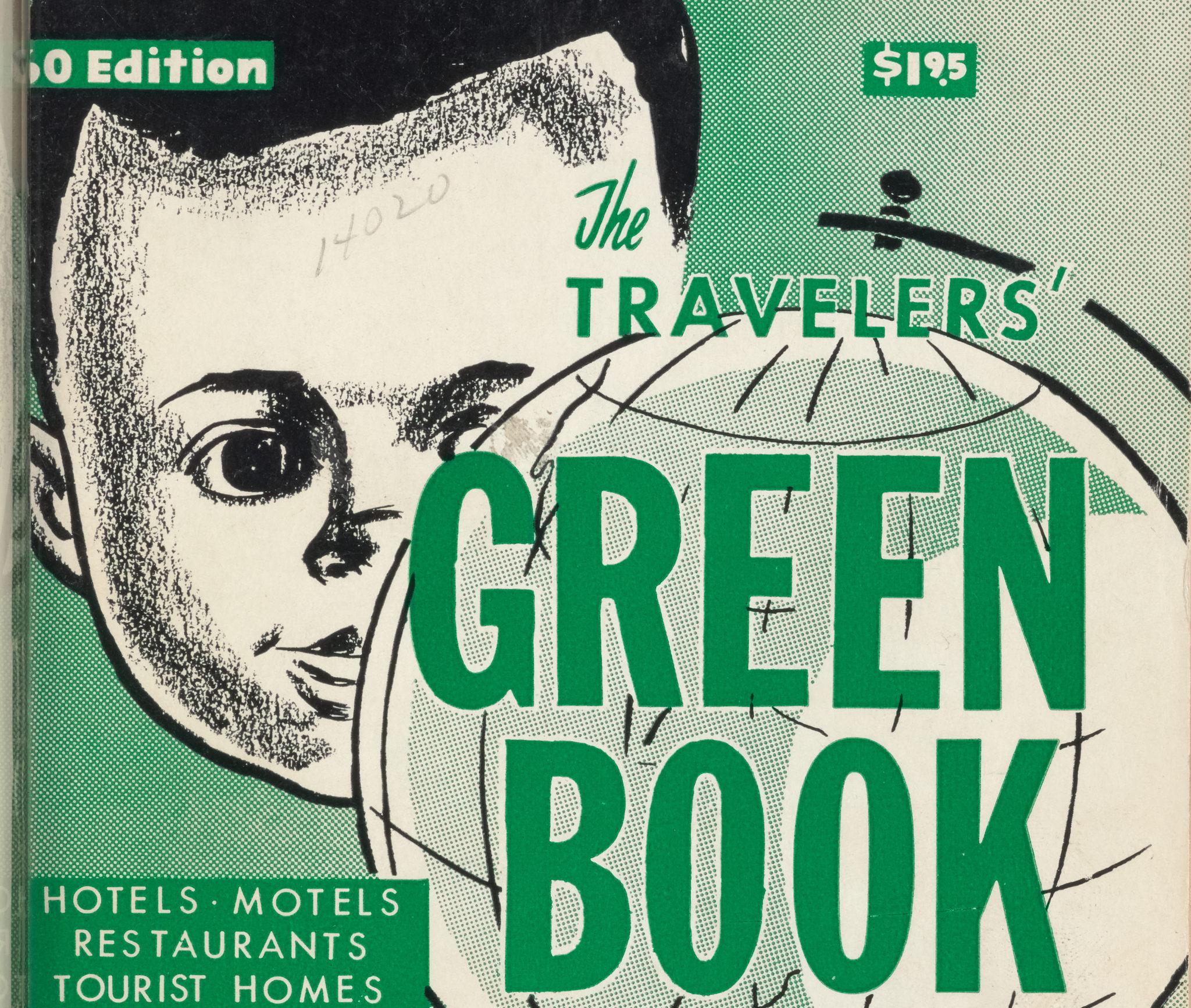

But beginning in 1937, there was a guide for black travelers that identified a city's safe hotels, homes and restaurants. Victor Hugo Green, mailman turned travel writer, worked with the nation's black mailmen to author the Green Book.

From 1939 until 1961, Denver was a part of that guidebook. Over the years, more than 70 businesses were listed in its pages.

- Mrs. G. Anderson's tourist home, 2119 Marion Street, listed for 14 years

Denver's most listed location was the boarding home of Mrs. Gustavia Anderson. The building was photographed in May 2014, but has since been demolished.

But from the 1940s to 1960s, the home was a major income generator for the Anderson family.

In fact, in the 1940 census showed that the college-educated Gustavia Anderson made all $600 of the family's reported income that year working as a governess.

- The Rossonian, 2650 Welton Street, listed for 13 years

Of course, one of Denver's most-listed locations was the iconic Rossonian. Much has been written of Denver's beautiful jazz hotel, a place that hosted Duke Ellington, Nat King Cole, Billie Holiday, and more.

After redevelopment attempts in the 1990s, the Rossonian closed in 2001 and has remained vacant ever since.

Yes, the stories of the Green Book are many, and they weren't just on Welton Street.

In fact, if you look at the establishments by year, you get a sense of the growth of black businesses in Denver.

- V. H. Meyers, 22nd and Downing, listed for eight years

The life of Zepha Grant illustrates how businesses spread. She was born around 1912 and was a smart girl who was allowed to sit in Kindergarten class before she was enrolled in school, according to Growing up Black in Denver.

Discrimination in her childhood meant going to the Violet Meyers drug store on 22nd Avenue, where she could not sit at the fountain.

You would just go in and buy what you wanted and leave with the purchase, she remembered. This continued until civil rights groups of black and white people joined together and marched together to break up segregation in Denver.

- Landers, 2460 Marion Street, listed for eight years

Grant started working at age fourteen in Landers beauty shop. She later attended Opportunity School's Cosmetology class and received her diploma.

- Zepha Grant's Beauty Salon, 2130 Downing Street, listed for one year

In fact, Grant went on to own a shop of her own one day. It was listed in the Green Book only in the 1957 edition, but lasted for much longer. Pearline Pigford Walton worked there for 45 years.

For Grant and her family, higher education was another important facet of life. Her daughter Billie Arlene was the first black person to graduate from University of Denver's journalism program. Years later, Billie Arlene became one of the coauthors of Growing up Black in Denver.

- Day & Nite, 1430 E. 22nd Avenue, listed for 10 years

Though none of the Denver business listed in the Green Book exist today, their shadows still fall across the city.

James Eskridge owns the block of buildings that used to house the Day & Nite cafe, listed for 10 years in the Green Book. He can remember hearing about the restaurant, but only dimly.

But today, the block of businesses at 1400 E. 22nd avenue include a natural hair shop and a barbershop.

"It means a lot that it had some sort of historic significance. I'm African American myself and there's a couple other African American businesses here," Eskridge said. "Now the rents that I charge are at the bottom end of the area, and that attracts a lot of different businesses."

For at least one person, a boarding house in the Green Book later became home after he bought the building in the mid-50s.

He didn't want his name or address used, but he was clear about his intention to stay in the home "until they throw dirt in my face."