Sunday marked the 75th anniversary of Executive Order 9066, signed by Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1942, which resulted in the internment of more than 100,000 Japanese-Americans in domestic concentration camps.

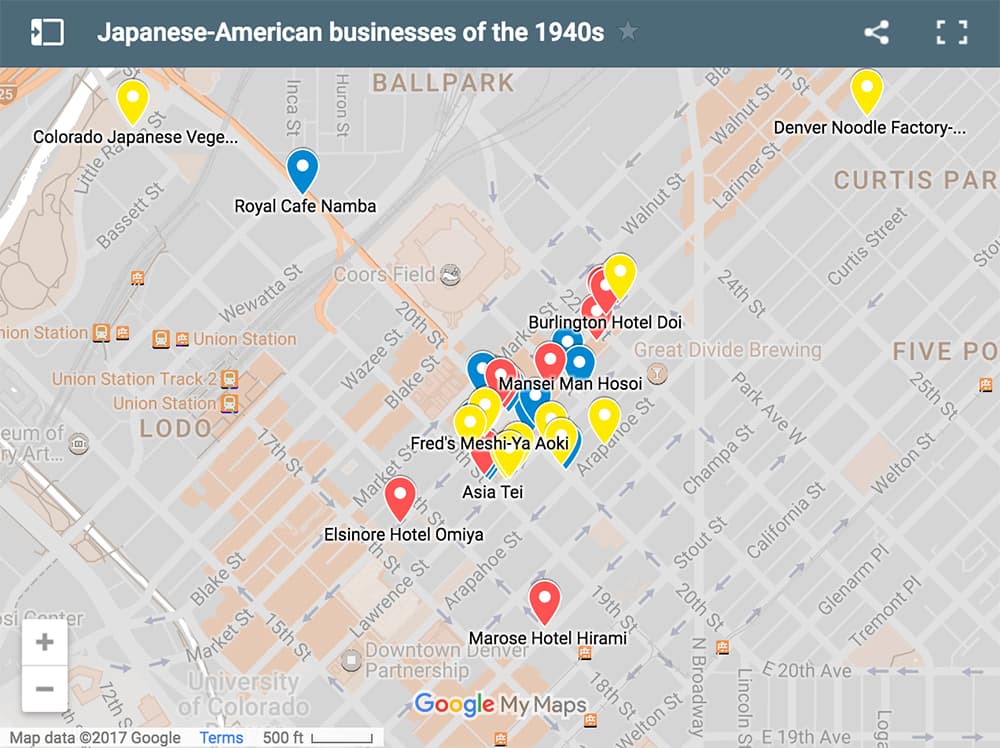

The order is remembered today as one of the country's darkest moments. Dark for Colorado, too, since one of the camps was located here. But in Denver, specifically, the effects of Japanese internment left a different kind of legacy: a surge of Japanese-American culture and business in the "Larimer Corridor" downtown.

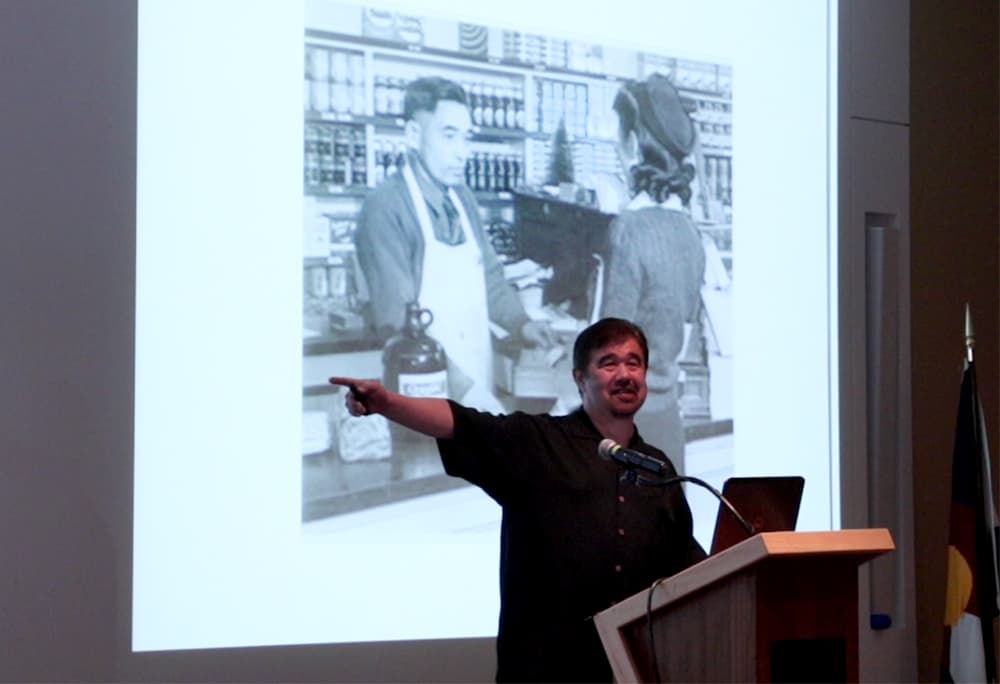

In memory of the wartime internment, the Mile High Japanese American Citizens League held a presentation at the History Colorado Center keynoted by Dr. Lane Hirabayashi, a professor at UCLA.

Hirabayashi is an expert on Japanese-American culture and has been studying the "importance of small business in Asian-American communities" for the National Park Service. He says you can look at small businesses as an "index" of a community.

The Japanese-American community in Denver during WWII must have been strong, Hirabayashi said, because Japanese business flourished here in the 40s.

Making a new home out east

FDR's order mostly affected families on the West Coast. For just two or three months after it was signed, families who could leave California, Oregon and Washington were able to escape detention. Many came to Denver, gravitating toward relatives and opportunity.

"It provided a haven for the Japanese-American resellers," Hirabayashi said, people with "capital and business expertise" who rebuilt after their forced relocation.

As families moved to town they would need temporary housing. As a result, Hirabayashi explained, the corridor saw a swell of hotels.

As they settled in, these first- and second-generation immigrants would need a familiar taste of home. Fishcake manufacturers and fish markets, tea rooms and lunch joints popped up in what became the Ballpark neighborhood.

"For a second," said Hirabayashi, Denver became "the center of the production of Japanese food."

Though many of these new residents would soon leave when California opened again, its lasting impression is visible. The Tri-State Denver Buddhist Temple, the corner of Sakura Square, was built in 1947 and still stands at the heart of what was once the "Larimer Corridor."

Unfortunately, this is still not a happy story.

The sad reality is that this whole boon was the result of massive tumult over race and security in wartime.

Many people who escaped detention, said Hirabayashi, were denied services on their eastward trips, then alienated when they arrived. The Larimer Corridor itself was the result of intentional segregation by the city, he said.

Even though Governor Ralph Carr famously committed political suicide defending the Japanese-Americans who relocated to Colorado, a community-wide fear permeated the state. And it persists.

“We’re still grappling with the long-term effects of an impact of incarceration,” Hirabayashi told the crowd.

Will we see race or culture-based detention again? He says that's an "exceedingly relevant" question. "We’re at the juncture of making a whole range of policy decisions."

That we can still see the effects of this singular population spike proves how impactful a relatively short moment of national policy can be.

"We need to think about the past," he said. "It’s not that distant, 75 years ago."

CORRECTION: This article originally said Sakura Square was built in 1947. It was updated to clarify that the Tri-State Denver Buddhist Temple, a foundational part of Sakura Square, was built in 1947. The apartment tower was built later in 1972.