Under the status quo, Colorado is likely to have to refund some $279 million to taxpayers next year, even as state lawmakers hunt for money for roads and cut funding to local school districts.

A bill sponsored by two Republican lawmakers -- state Rep. Dan Thurlow of Grand Junction and state Sen. Larry Crowder of Alamosa -- would let the state keep an estimated $133 million of that next year, $209 million in the following fiscal year and perhaps more in future years by changing how the revenue cap imposed by Colorado's Taxpayer's Bill of Rights is calculated -- provided the voters also agree in November.

To tinker with TABOR is a big deal in Colorado.

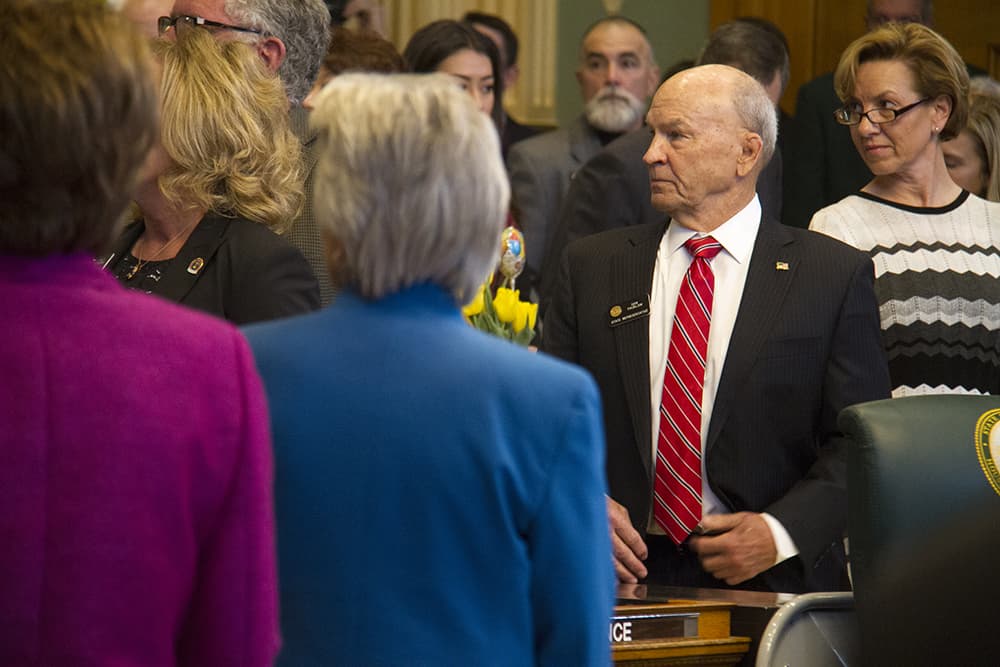

It says something about how dire many in the Capitol consider the budget situation that the bill passed out of the House Finance Committee Monday with three Republican votes (Reps. Polly Lawrence of Littleton and Phil Covarrubias of Brighton joined Thurlow, the sponsor). The bill has broad support from Democrats who will take any relief from TABOR's strictures that they can get, but faces a tougher fight in the Republican-controlled Senate.

Supporters believe it would pass the Senate if it could make it to the floor. The Republican majority is a single vote and, well, there's Crowder, the sponsor, and perhaps a few others who could be peeled away.

But Senate President Kevin Grantham has expressed skepticism about the idea.

“It’s an interesting concept,” Grantham told Colorado Politics. “We have to look at what’s the end result of what this bill will do. The end result will be more money out of taxpayer’s pockets. They like to call that state revenue. When I hear that, I hear money out of taxpayer’s pockets."

If the bill gets assigned to a kill committee, that could be that. And if makes it out of the legislature, it still has to get past the voters.

Thurlow said he supports TABOR, but it needs to be updated.

"If you like the idea of TABOR, as I do, the question is how far down you want to ratchet the size of government or if you want to let government grow at the same rate as the state economy," he said. "(HB 1187) asks the voters to make that decision."

Here's how the bill would work:

House Bill 1187, Change Excess State Revenues Cap Growth Factor, would change the way the state calculates the cap on how much revenue it can collect. Right now, the Taxpayer's Bill of Rights, approved in 1992, caps revenue growth by population and inflation. That means that in good economic times, the state can't use higher tax revenues that would otherwise be available because people are earning and spending more money. This bill builds on changes that voters approved in 2005 in the form of Referendum C, which suspended the TABOR limit for five years to allow Colorado to catch up from years when TABOR exerted a downward "ratchet" effect during the recession of the early 2000s. It also changed how the base was calculated going forward to remove the ratchet effect.

Under HB 1187, the cap would grow by the rolling five-year average of growth in personal income. That allows the state to capture more of the wealth generated during economic boom times and hold on to more money before it has to issue refunds to taxpayers. According to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Coloradans' per capita personal income rose from $41,877 in 2010 to $50,410 in 2015, or nearly 17 percent. However, change in personal income hasn't always been larger and likely won't always be larger than population plus inflation.

Here are a few years for comparison, according to legislative analysts. Numbers for 2017 and 2018 are based on forecasts.

- 2015: Population plus inflation: 4.3 percent; Growth in personal income: 3.5 percent

- 2016: Population plus inflation: 4.5 percent; Growth in personal income: 6.1 percent

- 2017: Population plus inflation: 3.1 percent; Growth in personal income: 6.6 percent

- 2018: Population plus inflation: 4.6 percent; Growth in personal income: 5.6 percent

Carol Hedges, executive director of the Colorado Fiscal Institute, said growth in personal income is a more accurate reflection of economic growth than the consumer price index and would help the state keep up with pressing needs in infrastructure and education.

The groups that showed up Monday to testify in favor of the bill ranged from the Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce to the Colorado Farm Bureau, from the Colorado Association of School Boards to the AARP.

Mizraim Cordero, vice president of government affairs for the Chamber, said TABOR's restrictions make it difficult for the state to invest in things nearly everyone says they value, like roads and education, things that boost the state's economic competitiveness in the long-run. In fact, the Chamber supports removing all revenue and spending restrictions.

"We take this position with resolve because we realize this change would place critical decisions in the hands of the legislature," he said. "We believe we can hold legislators accountable."

Opponents of the bill say it circumvents TABOR and the will of the people.

These include small-government groups and long-time backers of TABOR. Instead of changing the way growth is calculated, just ask the voters to approve higher taxes, they say.

"It is bills like this that make Trump possible," said Jon Caldara of the Independence Institute. "It’s another attempt to make government bigger by changing the rules from the inside."

Caldara knows what lawmakers know: Colorado voters almost never vote for tax increases, but they passed Referendum C. Asked if he believed voters weren't smart enough to understand the measure and make an informed choice, Caldara said the language, like Referendum C, was "very deceitful."

Penn Pfiffner, chairman of the TABOR Foundation, said that because TABOR was a constitutional amendment, any change to how the cap is calculated should also be an amendment. That would mean a much higher bar to get out of the legislature and onto the ballot and a much higher bar to pass -- 55 percent of the voters rather than a simple majority, under Amendment 71 approved last year.

"To do what you want to do, it has to be done in the right way," he said.

But HB 1187 amends Referendum C, which itself was a simple statute that changed how TABOR was implemented, not TABOR itself. Local jurisdictions like cities and school districts can also opt to "de-bruce" (after TABOR author Douglas Bruce) and remove the cap entirely with the blessing of a simple majority of the voters.

This is the language voters would see on their ballot if the bill passes:

Without raising taxes, may the state increase the amount of money that it annually retains and spends under the voter-approved revenue change from 2005 by allowing an annual adjustment to the amount based on the recent average change in Colorado personal income instead of an adjustment for the population change and inflation?

"We go to the voters and we say, here is a proposal that we think is good," Thurlow said. "My premise is that the voters are smart enough and can be trusted to make that decision."