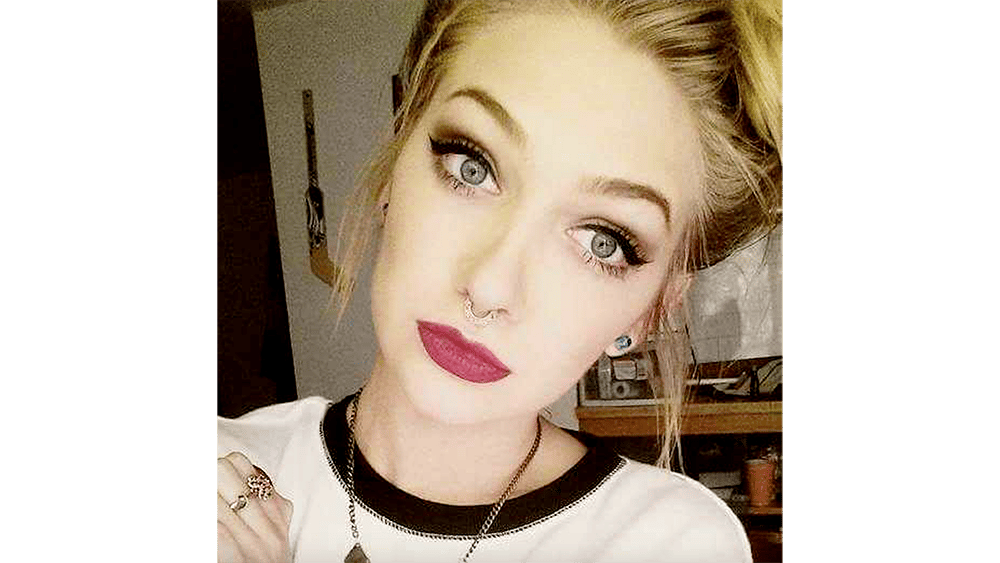

The father of a young woman who was stabbed to death early Christmas morning believes Denver police officers made a serious mistake that cost his daughter her life.

Not long before Kayla Burke was killed, Denver police officers were at her boyfriend's apartment for what is known as a civil standby. Burke was leaving, moving back to her mother's house in Grand Junction. She needed to get a basket of clothes from the apartment after a fight, and she must have felt she wanted someone else there when she went back into the apartment.

According to the probable cause statement in the case, Burke, 21, told officers that she would be fine waiting for a ride outside the apartment in the 1400 block of Pearl Street, near Colfax in the Capitol Hill neighborhood. The officers left. It's not clear from publicly available records how much time passed, but when people in the area called 911 to report a stabbing around 2 a.m., the very same officers responded and found Burke already dead. Joseph O'Neill, 20, a friend of Kayla Burke, was seriously injured in the same stabbing.

Marshall Westcott, 23, Burke's former boyfriend, is charged with first-degree murder and attempted murder in the case.

Sam Burke is a grieving father, but he's also a retired law enforcement officer with 25 years of experience and hundreds of domestic violence calls under his belt. He said he never would have left someone who was in the process of leaving a relationship standing alone right outside the apartment of their former partner.

"I've been to hundreds and hundreds of domestics, and I know they are the most volatile situations that change in a split second from everything's fine to very dangerous," he said.

He said every friend in law enforcement has the same question about this case: "Why was she left there on the street at 2 a.m. within 30 feet of him so he could do this?"

Citing the open murder case, Denver police declined to answer questions about how the civil standby was handled. Citing the same open case, the department also declined to provide the CAD reports that would show when the officers arrived at the first call and when they left -- that is, just how soon before the attack they were with Kayla Burke outside the apartment. However, when the call for the stabbing came in, they were close enough that they were the first ones on the scene and reported in the probable cause statement that they recognized Westcott from the civil standby.

Sam Burke didn't know about the civil standby until he read about it in Denverite's report of the murder. He said investigators only told him there had been a verbal dispute earlier in the evening.

"They kept that from me, knowing that I'm a cop and I know how things work," he said. "If it's a verbal and nobody wants to leave, your hands are tied, but if somebody wants to leave, you facilitate that."

Sam Burke said he knows the officers who responded "must be torn up about it." He wanted to talk about the case in the hopes that similar calls are handled differently in the future.

I asked Denver police if they could talk about what training officers get around resolving civil standbys. The written policy talks about what to do if one of the parties is uncooperative but not about when or whether to leave someone in front of the home they just asked for police protection to enter.

This is the entirety of the written policy on civil standbys in the department's operations manual:

- The recovery of a citizen's personal property in the possession of another is a civil matter between the two parties. The only legal authority of the police is to prevent a breach of the peace or to take action on other criminal activity.

- When officers are requested by a citizen to assist in recovering personal property, the officers should escort the citizen to the location and stand-by while the citizen makes their request. If the person in possession of the property refuses to release it, officers should escort the citizen complainant away from the property and advise them that they may initiate further civil action on their own.

- If the person in possession of the property agrees to its release, the officers should stand-by for a reasonable time while a reasonable amount of property is removed. The officers must remain neutral in these situations and are not to actively participate in the recovery.

- Under no circumstances can property be removed without the presence and permission of the person having authority and control over the location where the property is being stored.

The department emailed a written response that said the resolution of civil standbys depends on the officer's discretion.

"Denver Police officers, through overall training and experience, learn how to appropriately conclude the vast range of service calls they handle," the email said. "No two situations are the same, so officers must use discretion based on the circumstances to determine when an incident has been resolved and their continued presence does not appear to be necessary. Due to the changing circumstances an officer may face, there is no specific training regarding when a civil standby call is concluded."

Amy Pohl, a spokeswoman for the Colorado Coalition Against Domestic Violence, was cautious about criticizing the police response. When someone is leaving a relationship that was controlling or abusive, it's important that the people trying to help don't disempower the person further. Ultimately, the victim gets to decide how she wants to handle things, Pohl said. That said, leaving can be a very dangerous time -- 75 percent of all domestic violence homicides occur when the victim is trying to leave the relationship.

"If someone requests a civil standby, they clearly are feeling unsafe, and they need that support to feel safe," Pohl said. "So it is concerning when the civil standby ends at the door. At the same time, law enforcement is trained to assess risk. We also want to empower survivors to make their own decisions."

Right now, we don't know what type of conversation the officers had with Kayla Burke.

Pohl hopes it went something like, "I know you're saying it's okay to leave you here, but I want you to know that often when someone decides to leave a relationship, violence can escalate, so I'm not comfortable leaving you here."

"They might have said that," she said. "I hope they would have."

Sam Burke described his daughter as a talented artist with her whole life in front of her. He said he wasn't aware of any violence between his daughter and her boyfriend, though he recalls that he got angry that she lived with a male roommate. There are no public records that indicate any history of violence, such as restraining orders or prior assault charges.

Pohl said that's not uncommon. In Denver, over the last five years, in 55 percent of all domestic violence homicides, there was no prior law enforcement involvement. That's according to the Denver Fatality Review Board, which looks for patterns in certain types of homicides in the hopes of preventing some of them in the future.

"That escalation to physical violence can happen very quickly," Pohl said. "It can go overnight from these other means of control to extreme physical violence."

Pohl said there is no clear profile of who might become dangerous -- it would be easier to avoid such people if there were -- but there are certain things that correlate with a higher risk of violence. One of them is the presence of a gun in the home. Regardless of whether the gun itself is used in the crime, the presence of a firearm is associated with a 500 percent increase in the risk of fatal violence. And if one partner has a history of being violent in previous relationships, their current partner should take that seriously.

Other risk factors include:

- previous sexual violence in the relationship

- threats of suicide

- threats to harm or kill the other person

- abuse during pregnancy

- drug use

- strangulation in the past

Pohl cautioned, though, that in many fatal cases, none of these factors are present. The search for the red flags can be a way of assuring ourselves we would have seen it coming, Pohl said.

Sam Burke said he's all too familiar with that unpredictability, and it's why he wouldn't have left someone in his daughter's situation alone.

"The worst call that a cop can get is a domestic," he said. "They can turn on a dime. But whenever someone wants to leave on a domestic, I facilitate that."

Burke said that as an officer, he always thinks through the worst-case scenario from a course of action or inaction.

"Even if a victim says, 'Hey, I think I'm okay, I have a ride coming,' I park on the street. Or I put her in my car and relocate her. I know it's already a domestic. I always facilitate that. I always have."

Burke said the police should treat everyone the same, but he can't help but feel let down by what he calls his "law enforcement family."

"If they had known this was a cop's daughter, there is no way they would have left her," he said. "If there had been a cop car right there, this would not have happened, and she would be standing here today."

Pohl wanted to be very clear about something. While it can be dangerous to leave, that doesn't mean victims should stay or have to stay in their relationships. There are resources available to be help people be safer as they leave a relationship that was controlling or abusive, whether that abuse was physical or emotional.

Right now, there is no state domestic violence hotline, but the national hotline can help victims find resources among the 40 non-profits helping domestic violence victims around Colorado.

The National Domestic Violence Hotline is 1-800-799-SAFE.