There's a doorway to nowhere on the second floor of one of Denver's most popular bookstores. Hiding above eye level, it opens to nothing but a safety railing and the 16th Street air.

Until 1994, this was a connection to one of the elevated roadways that spanned miles of the central city. "The viaducts" shadowed Lower Downtown for nearly the entire 20th century, a modern wonder that first connected, then starved the heart of the city.

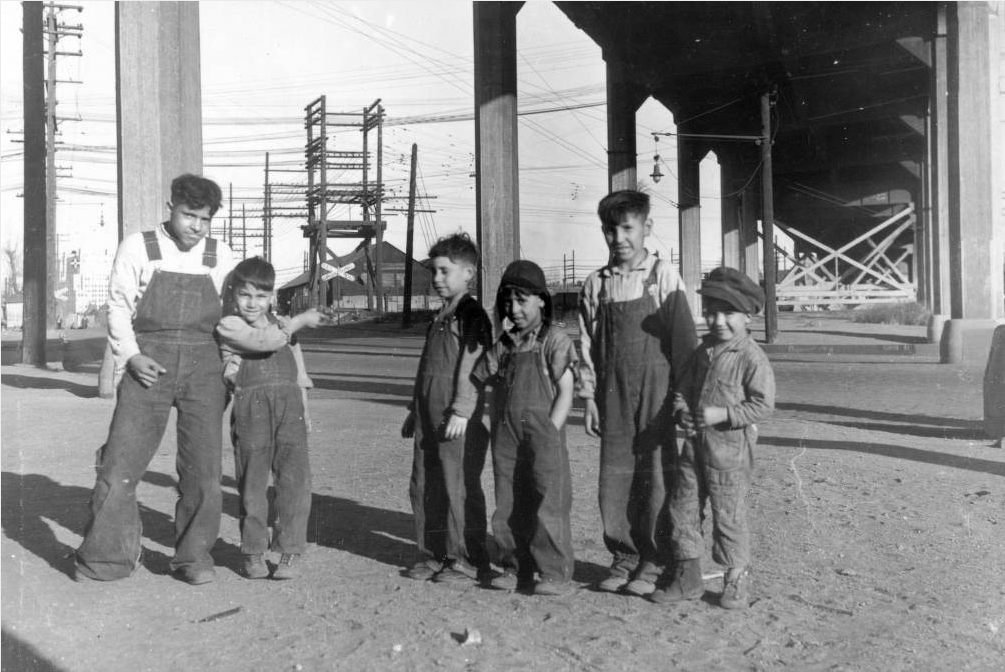

"It’s almost like a cathedral type of environment," said photographer Mark Kiryluk, thinking back to the images he captured of people adrift in the city's underbelly. "You've got this huge viaduct -- and below it there's just this quiet spot."

There's hardly any trace of them today, but the story of their rise and fall captures three distinct changes in Denver's history. From groundbreaking transit infrastructure to maligned scourge of downtown, this is the story of Denver's viaducts.

Why they were built:

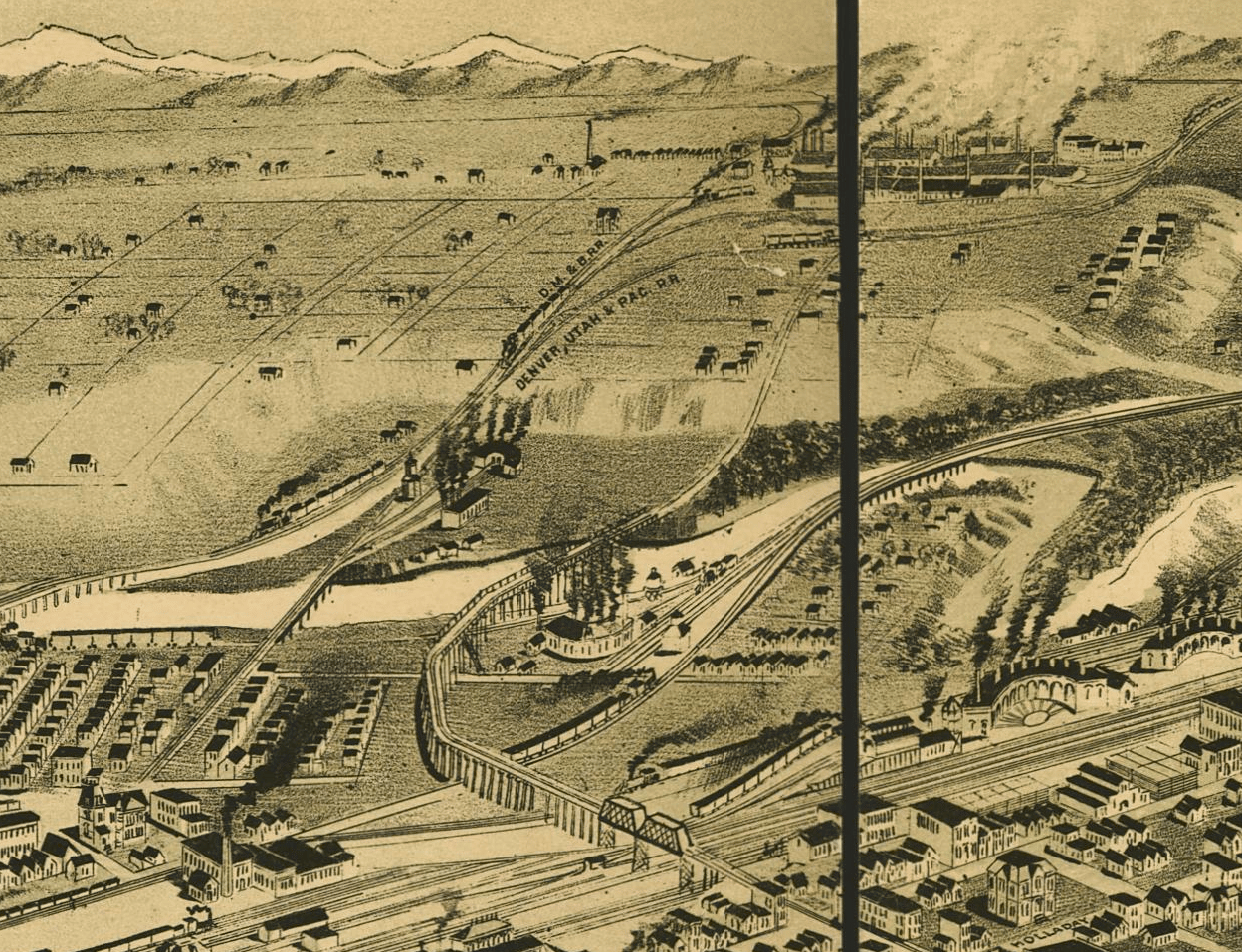

Denver's very first viaducts were built to link the city with the village of Argo, a company town built around a new smelter north of Denver. The Argo site today is near the border of Sunnyside and Globeville, around 44th and Pecos -- but in the 1880s it was separated from the city by miles of open fields.

"An easy route was needed to connect lower downtown with the rapidly growing community ..." Robertson wrote. "The new community needed public transit."

The first viaduct, illustrated above, allowed the city's horse-drawn streetcars to cross the rail lines and the South Platte, making Argo just an easy hour's commute from downtown. (Insert traffic joke here.)

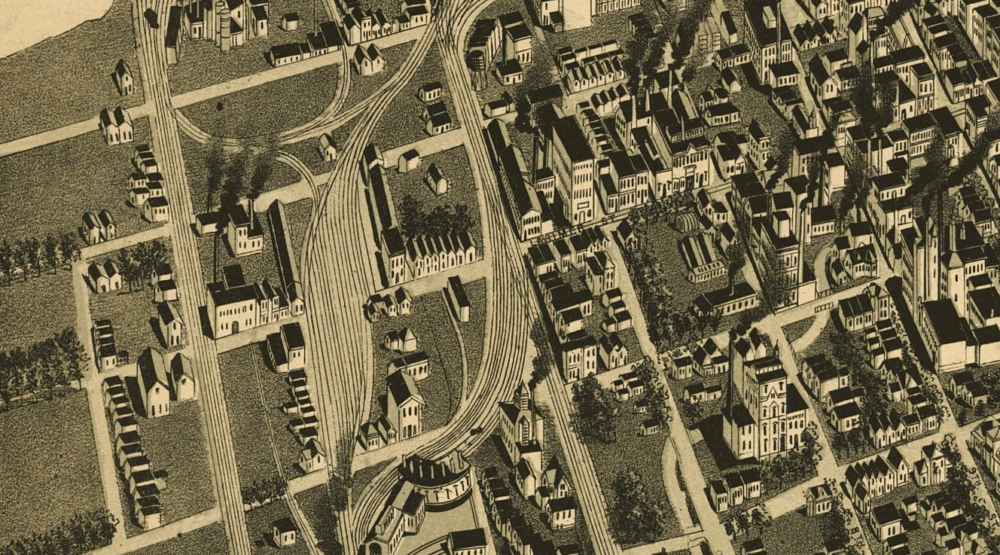

The city followed soon after with the first version of the 16th Street viaduct, which lifted off at Wazee Street and vaulted 3,700 feet through lower downtown and over the rails and river to touch down on Platte Street, according to Denver's Street Railways, Vol. 1.

Over the next few decades, similar structures would lift parts of Broadway, Colfax Avenue and 14th, 15th, 20th and Larimer streets, their wood planking gradually rebuilt with iron and pavement.

The purpose, in large part, was to make Denver safer. City planners had thought little of cross-hatching pedestrian and vehicle routes with the heavy rail that had defined the early city -- a layout that, combined with heavy alcoholism, was the cause of many deaths.

"A lot of them were falling asleep on the tracks and getting crunched, or walking in front of the trains and getting struck," said historian Kevin Pharris, owner of Denver History Tours.

And that public health crisis apparently kept demand for new viaducts hot -- much the same way Streetsblog today might point to the high fatality rate of automobile travel as compared to light rail.

"Part of the impetus for the viaducts was helping everyone, sober and intoxicated, get above the traffic," Pharris said.

Apparently, it was an effective argument.

Mayor Robert Speer wielded public outrage and some legal tricks -- such as a law that forced trains to proceed with extreme caution through parts of Denver -- to make the railroads chip in for elevated roads in the early 1900s. A single 1914 project, the Colfax-Larimer Viaduct, cost nearly $18 million in today's dollars.

What they changed:

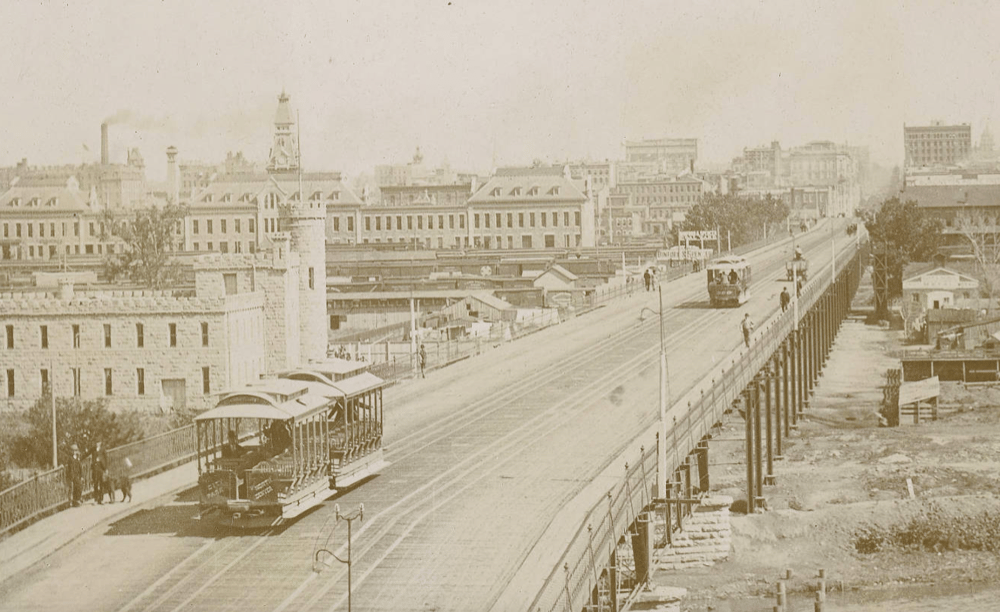

The viaducts certainly got people above the rails -- and they also got them in and out of downtown much more quickly. This new connectivity was particularly good for the streetcars, which were Denver's earliest form of transit.

"The first suburbs were streetcar suburbs -- they grew up around these streetcar lines going out to the neighborhoods," he said, listing off areas from Englewood to Littleton, Montclair, Washington Park and Golden.

"People forget that it was streetcars that first allowed people to move out of the city."

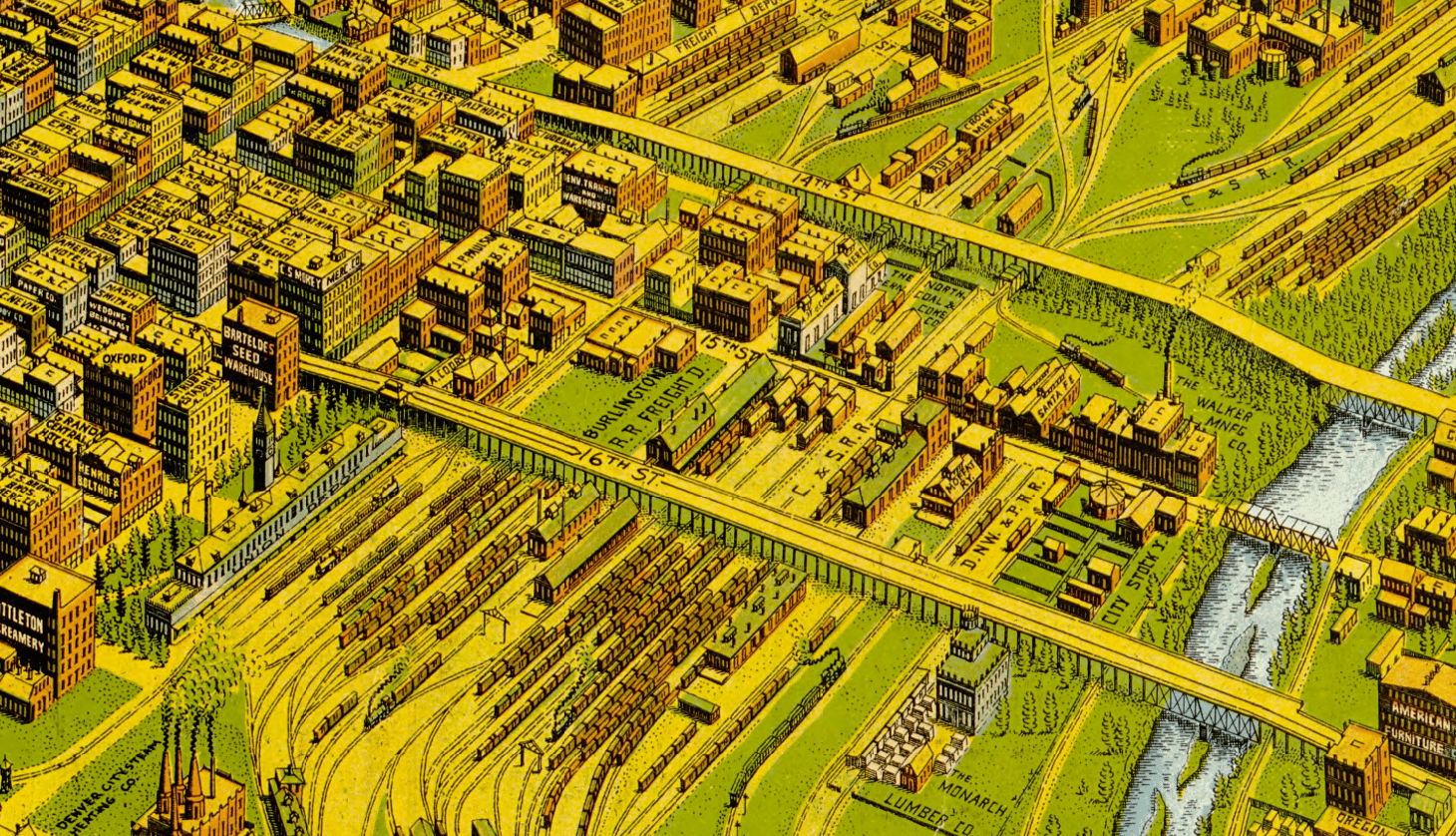

Over time, the streetcars were joined by automobiles. The last of the streetcars ran in 1950, leaving the viaducts as speedy routes for commuters from the new suburbs. They became, arguably, just another wound that was bleeding downtown dry -- and the structures left whole blocks aching for sunlight and air.

"It was really dark and gloomy underneath, as I remembered," Kiryluk said. "I was scared out of my wits -- I didn’t know who in the heck was down there."

Still, some people remember these spaces fondly. "We looked at the old buildings, climbed up and around the still-standing 16th Street Viaduct, breathed air that seemed much thinner and drier than what we were used to in Chicago," wrote Westword editor Patty Calhoun, describing her arrival in Denver in the mid 1960s.

Others spoke of a feeling of freedom in the cavernous spaces beneath the viaducts. And the Wazee Supper Club, now on a prime piece of Denver real estate, keeps a photo on its wall of the metal skeleton that once stretched over 15th Street.

For photographer Diane Rabson, the viaducts were a reminder of home.

"I grew up near an elevated train structure - the subway runs above ground some places in Brooklyn," she said.

"And so, for some reason the viaducts in Denver reminded me of those structures - and how happy I was as a kid in Brooklyn."

When they came down:

By the 1980s, many of the viaducts were in poor condition, some nearly a century old even in their rebuilt forms.

"Cockroaches hide in shadows -- if you let the sun in, they'll run," one person involved in those conversations told Pharris, the historian. Pharris doesn't agree that a person should be referred to as a roach -- but the quote, whose speaker he can't recall, neatly captures the idea that was circulating among influential people at the time.

If they could only change the environment, the thinking went, then downtown could replace its vacant lots and unwanted people with something more like today's LoDo.

Wazee Supper Club turned the demolition of the 15th Street viaduct into a celebration, running radio and television ads that "made light of the frenzied bulldozing as a historic lower downtown event. Rather than lure diners with discount dinners, the new spots invited customers to view the disruptive action outside the restaurant's front windows," as the Rocky Mountain News reported in 1991.

The structures were largely gone within a few years -- except a couple.

Colfax Avenue today runs on a viaduct for part of its length. Interstate 70 drives through northeast Denver on hundreds of stilts. And the rebuilt 23rd Street viaduct lifts Park Avenue high above the new apartment complexes north of Union Station, giving drivers an unobstructed view of the city skyline, if only for a moment.

Have a viaducts photo or memory to share? Email me.

Correction: This story earlier stated that Argo was near 34th and Pecos. It was 44th and Pecos. It also misstated the last date of streetcar service. 1950, not 1951. Sorry!