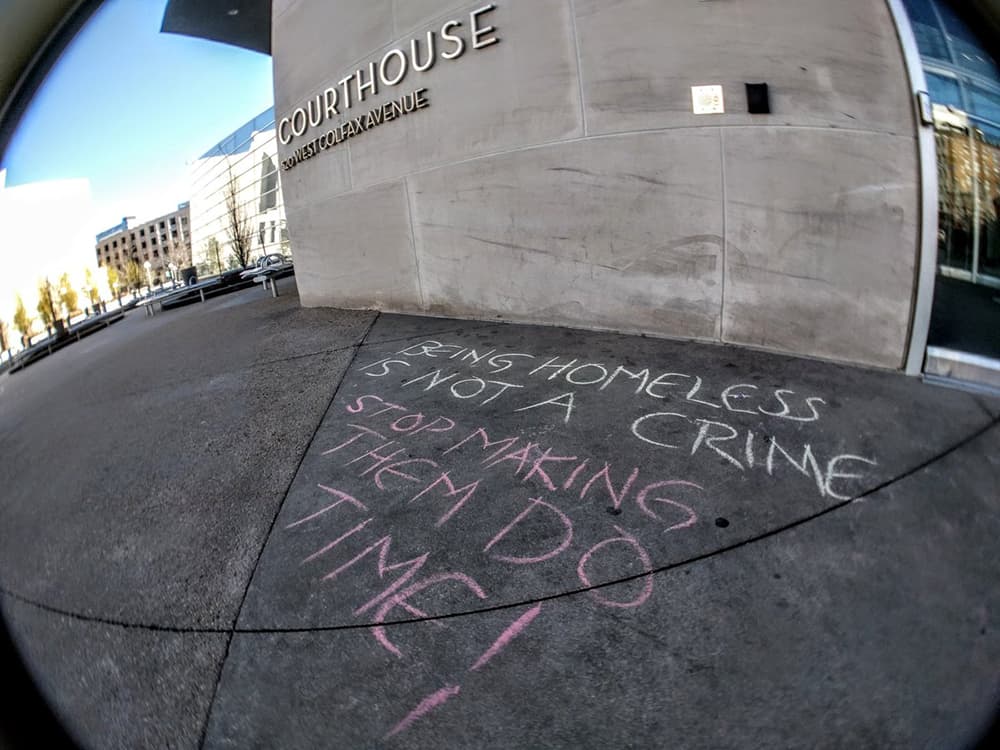

After three hours of deliberation and despite the defendants' insistence that their crime was actually survival, a Denver jury on Wednesday found three people guilty of violating the city's urban camping ban.

Jerry Burton, Randy Russell and Terese Howard were each charged with violating the camping ban and with interference with police for a series of incidents that occurred on Nov. 28. Burton and Russell were both ticketed during a "sweep" near 27th and Arapahoe in the morning, and then all three were ticketed during a gathering of homeless people and activists in front of the City and County Building that evening. The interference charges, according to prosecutors, were because they took far too long to comply with orders to move.

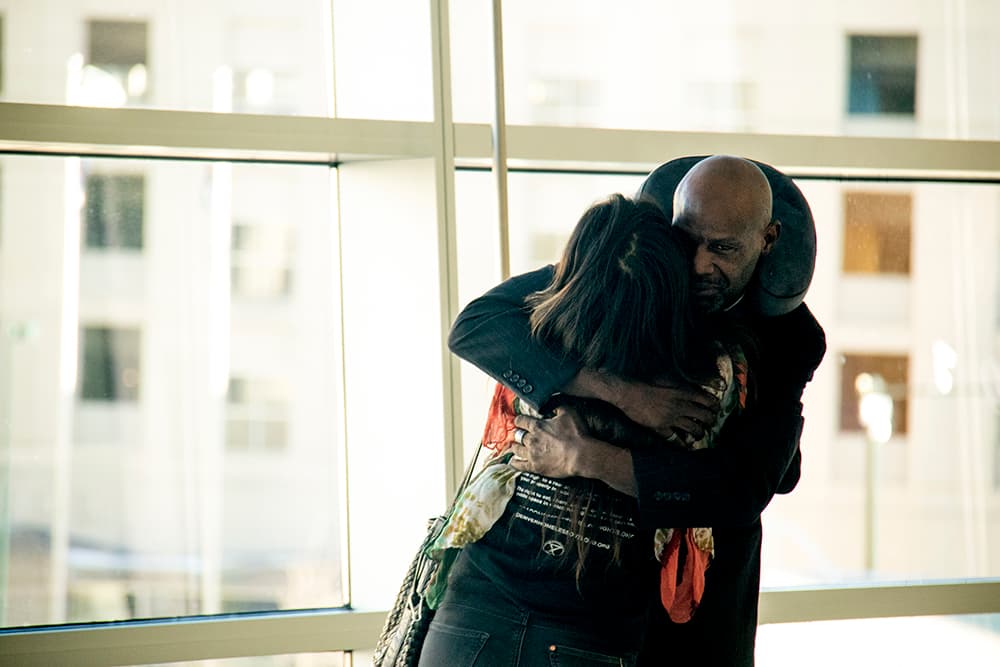

Burton and Russell were found not guilty of the first count of interference at 27th and Arapahoe, but all three were found guilty on the remaining charges. They were sentenced to one year of unsupervised probation; the only requirement to satisfy it is court-approved community service. The defendants may appeal the conviction.

"Our jury was just following the law," defense attorney Jason Flores-Williams said after the verdict was read. "Unfortunately, it was an unjust law. Justice died just a little bit today."

Howard is an activist who has housing but spends many nights outside with homeless friends. Burton had been homeless for two years on the day he was ticketed twice, but he has housing now through a voucher program for military veterans. Russell remains homeless and continues to sleep outside. He's disabled and by his own account struggles with mental health issues.

Rather than pay a fine and move on, they pleaded not guilty and took their tickets to a two-day trial at which they focused on the inconsistent enforcement of the law and the inadequate nature of the shelter system. Denver bans people from sleeping outside with any shelter, even a blanket or sleeping bag. The city says there is enough shelter space for everyone, but some homeless people prefer to sleep outside rather than on thin mats on the floor crammed in next to other people who may be sick or unruly.

In a statement, the City Attorney's Office said the case was unusual because it represented an act of protest.

“The tickets and this case are uncommon as the three individuals were acting in protest and sought arrest in order to challenge the camping ordinance in court," the office said in an emailed statement. "The city’s approach to enforcing the camping ordinance has been and will continue to be to connect those who are living on the streets with the help that they need like housing, a job and healthcare. If that doesn't work, people are given notice and warnings multiple times before any enforcement action is taken. Issuing tickets, as was the case here, is a last resort but a necessary action if individuals are knowingly violating the law and unwilling to comply."

There was little doubt throughout the trial that Burton and Russell had engaged in the acts alleged by the city. While Flores-Williams tried to cast doubt on whether officers had complied with portions of the law that require them to offer assistance -- or whether they had done so in anything but the most pro forma manner -- prosecutors documented repeated warnings to Burton and Russell to show that they were aware of the city's laws and chose not to go to a shelter. This was because they needed to show that the defendants "knowingly" violated the law.

Burton and Russell repeatedly responded to questions about whether they were camping by reframing it as "surviving."

"I feel I was not camping," Russell said. "I did not have no s'mores. I was not having a good time."

To avoid the constant back and forth, prosecutors eventually adopted the survival language, leading to the very uncomfortable question from prosecutor Bradley Whitfield: "They (police) told you that what you were doing -- surviving at 27th and Arapahoe -- was against the law?"

"Well, if there is a law against surviving, I think we all need to rethink that," Burton said.

Howard testified that police officers often sent mixed messages about what would be tolerated.

"I've also had many conversations with police officers where they talked about getting blankets for people, where they talked about what would be a good place to sleep," Howard said. "'Maybe if you go down by the river, you'll be okay.'"

While Flores-Williams was not successful in securing acquittals for his clients, he repeatedly demonstrated that it's camping where you can be seen that is the problem, not camping in and of itself. Most of the homeless people who left the City and County Building early on the morning of Nov. 29 didn't go to a shelter but instead to nearby alleys to sleep. Burton, though, went to the VA hospital.

"The reason I go to the VA is they let me lie down and warm my body up," said Burton, who has a degenerative bone disease and is in the process of applying for disability. "Then I can move."

Burton's testimony also highlighted the limited utility of police officers handing homeless people the same list of services over and over. On Nov. 28, Burton had already availed himself of services and had a housing voucher, but he hadn't been able to find a landlord who would take it yet. He said he would not go to Samaritan House because he used to live and work there and did not feel he was treated with respect.

Prosecutors, for their part, focused on the narrow requirements of the law.

That is, the defendants knowingly camped on public property in the city and county of Denver, which is illegal and which has a clear definition in the law. That definition is residing or dwelling temporarily with any kind of shelter and has nothing to do with whether you're having a good time.

Prosecutors repeatedly objected to testimony that tried to bring in larger questions about how the city responds to homeless people, even objecting to Burton commenting on how fortunate he felt to have housing when it was snowing Tuesday. In their closing arguments, they told the jury their job was the answer only the question of whether the defendants violated the law as it is today.

"This case is not about the answer to homelessness," Whitfield told the jury in his closing argument. "It is about whether the city has met its burden to prove beyond a reasonable doubt the elements of the offense."

And it was "indisputable," he said, that the defendants had camped and had done so knowing it was illegal.

"By his own testimony, he had a tent and he was in a sleeping bag," Whitfield said of Burton. Similar arguments applied to Russell and Howard.

What the defense cast as inconsistent enforcement that sent mixed messages, the prosecution cast as giving the defendants opportunity after opportunity to avoid criminal penalties. There were more than a dozen other people outside in the Ballpark area in the morning and more than that at the City and County Building. No one else got tickets, they said, because everyone else complied.

Flores-Williams was not allowed to tell the jury explicitly to engage in nullification, a practice in which jurors return a not guilty verdict in spite of the evidence because they simply disagree with the law, and he urged the jury to "apply the law" in his closing arguments. But he also urged them to bring their own life experience to bear.

"All I want you to do is what is right and what is just," Flores-Williams told the jury.

Out in the hallway waiting on the jury, supporters of the defendants said repeatedly that "if ever a case called for nullification, this is it."

It was not to be.

Judge Kerri Lombardi called in a number of sheriff's deputies before the verdict was read, and one woman was escorted out after yelling that Lombardi should recuse herself from the sentencing.

The defendants could appeal their convictions, and a guilty verdict better positions them to challenge the law itself than an acquittal would have. The Colorado Supreme Court declined to take up a challenge to Boulder's camping ban back in 2011, essentially upholding that city's law and setting the stage for Denver to enact its ban in 2012.

Advocates have said they hope higher courts would view a challenge more favorably now than in the past, while the City Attorney's Office has confidence in the constitutionality of its law.

Democratic Reps. Joe Salazar of Thornton and Jovan Melton of Aurora introduced legislation this week in the state House that would create a "right to rest." Similar legislation was killed last year after cities raised strenuous objections.