Developers could go tall -- 10, 12, even 16 stories high -- around the A Line's 38th and Blake station in booming River North -- if they make a portion of their residential units affordable. The ratio works out to roughly 10 percent of the units in the new buildings' upper floors.

That's the proposal that Council President Albus Brooks and Denver's Community Planning and Development staff hope to roll out this summer and get through City Council this fall.

The zoning changes to allow for more height around the A Line were adopted by City Council last year with this basic framework in mind. Now Brooks and city planners are nearing the end of a stakeholder process with developers and community representatives that will pin down exactly how many units will be required and what "affordable" will mean.

While non-residential projects could pay a fee instead, the proposal also encourages commercial and mixed-use projects to include space for businesses that benefit the neighborhood or help preserve its character as a warehouse arts district: galleries, studios, grocery stores, child care centers and incubators for small businesses.

There's also a design overlay in the works to prevent, in Brooks' words, "the kind of stuff you see on Fugly." (That's the Facebook group that lambasts much of Denver's contemporary architecture.)

"This area is ripe for redevelopment," said Abe Barge, 38th and Blake project manager with Community Planning and Development. "It has great transit access. But there is also making sure it’s the right kind of place. That means having great design and affordable housing, and RiNo wants to preserve its identity as an arts district."

The goal is a diverse community with housing for a range of incomes.

A lot of what's getting built around light rail stops -- or anywhere -- is pretty high-end, and there's a sense that won't change unless the city intervenes.

It's different from the old inclusionary housing ordinance, which required developers to make 10 percent of their units affordable but much more often resulted in them paying money to the city instead. This approach is called "value capture." Developers don't have to do anything, but if they build taller and make more money in the process, the city would get to capture some of that value in the form of more affordable housing.

But if the city doesn't create the right incentives, that might not happen.

"Some of this is very aspirational," said Kyle Zeppelin, developer of TAXI project and several other projects in RiNo. "It’s very out of touch with reality."

The market conditions aren't ripe for 12- and 16-story buildings even without affordable housing, Zeppelin said, so the height changes are fueling land speculation that drive up costs in an area where many developers will end up doing smaller projects with no affordable housing.

Jamie Licko, executive director of the RiNo Art District, said she likes the general concept, but it will be important to get the details right.

"If this goes through and developers stick with the base heights and don’t take advantage of those densities, we will have missed on this," she said. "Ultimately what we’re trying to do is build density around the transit. That is the goal of the zoning overlay -- building this walkable, bikeable neighborhood around the station."

"That’s where the magic is: Where is that number?" she continued. "Developers will have to make some concessions, but we need developers to want to use this."

So what's the plan?

First, let's review two things that happened at about the same time last year. Denver City Council adopted a linkage fee that requires all new development -- residential, commercial, industrial -- to pay a fee that goes into an affordable housing fund. Residential developers could choose to build affordable units as part of their project instead of paying the fee, though the ordinance assumed most wouldn't take that option. There's a ratio that tells developers how many units they have to build for however much square footage.

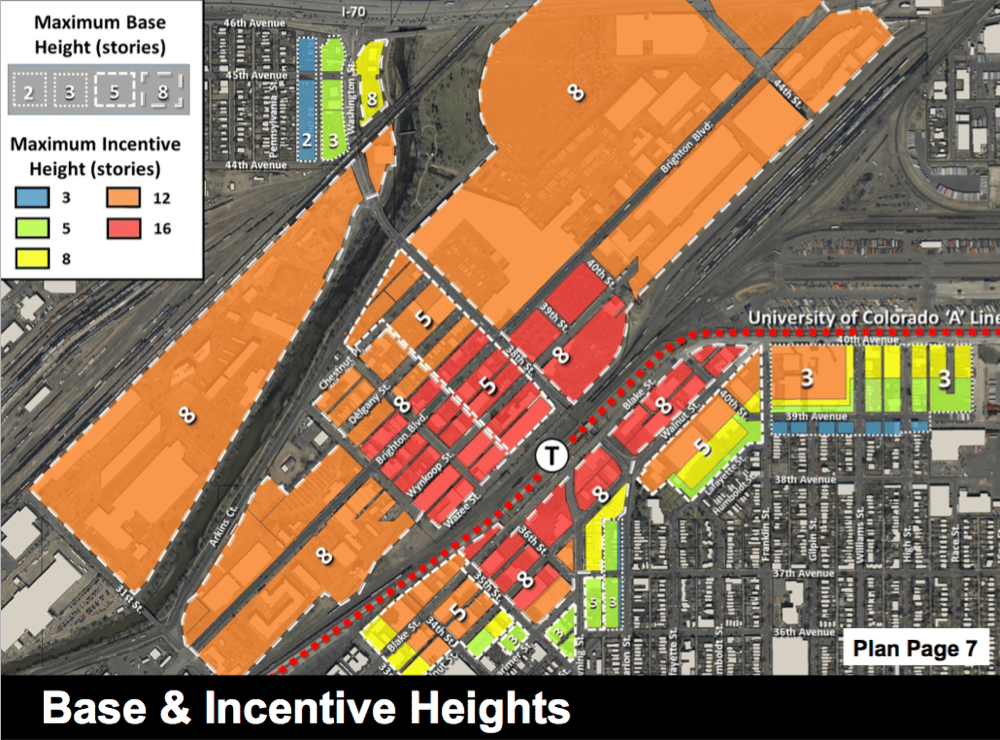

And Denver City Council also adopted the 38th and Blake height amendments to encourage taller, denser development around the train station. Here's a helpful map. The written numbers are the base heights now allowed around the station area, and the colors represent the taller heights that developers can use if they include affordable housing.

Let's use one of the orange-shaded areas with a 5 as an example. Right now, a developer who built a 75,000-square-foot, five-story residential building would have to pay $112,500 or include one affordable housing unit in the project.

Under the new proposal, the owner of the same piece of property could build a 108,000-square-foot, 12-story building IF they included 10 affordable housing units. That number is arrived at by taking the ratio used in the five-story scenario, increasing it by a factor of five and applying it to the second seven stories. It would represent roughly 10 percent of the units in many projects.

Significantly, there's no option to pay a fee and buy your way into the taller heights -- it has to be actual housing.

"Affordable" would mean that someone earning up to 80 percent of area median income wouldn't spend more than a third of their household income to live there. That's $47,040 for a single person and $67,120 for a family of four. Developers who built for people earning less than 60 percent AMI would be eligible for assistance from the city's new housing fund.

Brooks also believes the city can require developers to set aside rental units as affordable. The Telluride court decision found that inclusionary housing ordinances amounted to rent control, which is illegal in Colorado. Brooks said this is different because the developers don't have to offer affordable units. They would be voluntarily entering into an agreement in exchange for more height.

What about a commercial property, like offices or a hotel?

It doesn't make a lot of sense to stick a few random apartments into a non-residential building, and the initial thought was that these projects would just pay a fee.

But affordable space needs in RiNo extend beyond just housing to the artists' spaces that made the neighborhood what it is. And as more people move there, if it's going to be walkable, bikeable, etc., it needs the normal sorts of neighborhood amenities. Right now, those are lacking. If you've been up on Brighton, you know there are a lot of storage units.

"Space for artists' studios or small local businesses, we think that’s critical," Licko said. "We hope to be pioneers or innovators on that affordability front. ... Right now, there are not a lot of models."

The proposal would allow commercial developers to pay a fee -- again, at a five times greater rate than the normal linkage fee -- to build tall, or they could provide affordable commercial space or offer a subsidy to tenants under a "community benefit agreement."

Qualifying tenants could be nonprofits, galleries, maker spaces, arts education groups, studios, grocery stores, pharmacies, child care centers and clinics.

This is going to be more complicated to work out than affordable housing. You can place a deed-restriction on a unit, and if one family moves out, there will always be another family who meets the income requirements and needs a place to live. But if you offer a subsidy to a grocery store and it doesn't work out, you might not find another grocery store that wants to move in.

Barge said the Office of Economic Development is working on how to structure these agreements to provide the necessary flexibility and guarantees.

Will it work?

On the city's to-do list as this proposal moves forward is an analysis of the financial feasibility of the various options. What's the break-even point for a five-story building under the current scenario? For a 12-story building with no affordable housing? For a 12-story building with affordable units as envisioned by this proposal? This plan could change as a result of that analysis or additional feedback.

"The challenge is calibrating to the market," Barge said.

"Just because some scenarios won’t work under current market conditions doesn’t mean they wouldn’t work in the future. Hopefully we would have some scenarios that would work out the gate. The community wants to see additional development to leverage our investment and see that increased development generate the affordable housing and the community-serving uses."

Michael Mathieson, a developer who was part of the group that developed the proposal, said he thinks the math will work for lots of projects, including his own near 39th and Blake Streets. He wants to build a 200-unit hotel tower and a 12- to 16-story residential tower. He was going to do apartments but is now considering condos.

"If you don’t do it, there would be very little affordability over there," he said. "The city does need affordable housing. It’s a crisis."

Mathieson sees the future of the city at stake. To be a great city, Denver needs a diversity of incomes, races and backgrounds, and without the affordable housing incentives, development in RiNo would mostly be for the affluent.

"Of course, for ultimate profit, it’s better for the developer to not do any affordability, but that’s not good for the city," he said. "It's not good for the long-term viability of the city.

But Zeppelin said high-rise construction is so much more expensive per-square-foot that the affordable requirement will kill some projects. Even without those requirements, there isn't a market right now for such tall buildings. He said it would have been better to set the heights at eight or 10 stories and require everyone to include affordable units.

He described the heights as a "windfall" for developers, the affordable housing requirement as a "gimmick," and thinks the heights are just too damn high.

"There's a real loss of livability for the neighborhood around them," he said, particularly for the Cole neighborhood, which sits to the east. The heights do step down as you approach the one- and two-story single family homes of Cole, but it's going to be a change, for sure.

Licko said "universally, all developers are concerned. Even the folks in our organization, they have certain levels of concerns."

Brooks said he's heard from developers who are supportive and those who are not, but this plan isn't primarily for people with projects in the works today. It's for the projects that will come over the next 10 to 20 years as the area fully redevelops.

"I wish someone had done something like this for us 10 years ago," he said.

Licko said that she hopes what happens in RiNo can serve as a model for other gentrifying neighborhoods with transit.

"It has the potential to change -- in a really positive way -- the trajectory of RiNo, and I hope it can serve as a template for other neighborhoods that are struggling with similar challenges," she said.