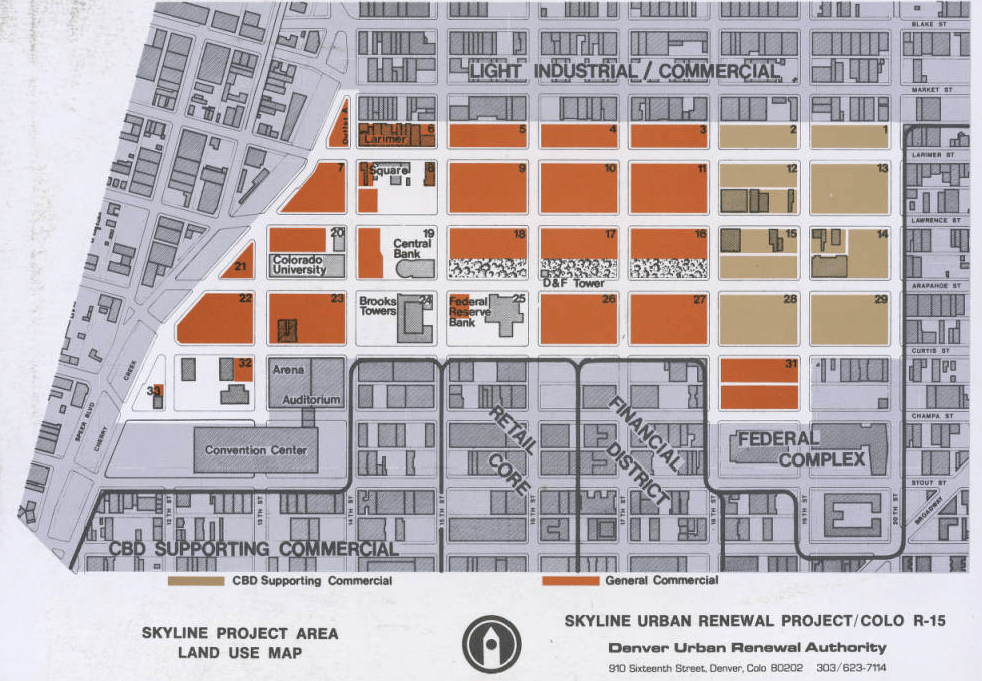

In 1971, the demolition project that loomed over downtown Denver seemed all but unstoppable. The city of Denver was on a campaign to seize and rebuild 30 blocks of Lower Downtown and historic buildings were falling all throughout the central city.

"They weren’t going to let anything stand. They wanted to remake downtown into their vision, which was all new high-rise office buildings ... The same thing we're doing right now," said Jim Judd, sturdy and talkative at 91 years old.

Judd was one of a small band of property owners, civic figures and history lovers who banded together to hold back the wrecking balls. This early resistance would become a modern effort to preserve historic Denver, resulting in the preservation of Larimer Square and the Molly Brown House and scores of other landmarks.

We wrote last month about the broad strokes of this critically important time in Denver's history. Now we've got a much more focused story about the fascinating way that politics and money shaped those early days.

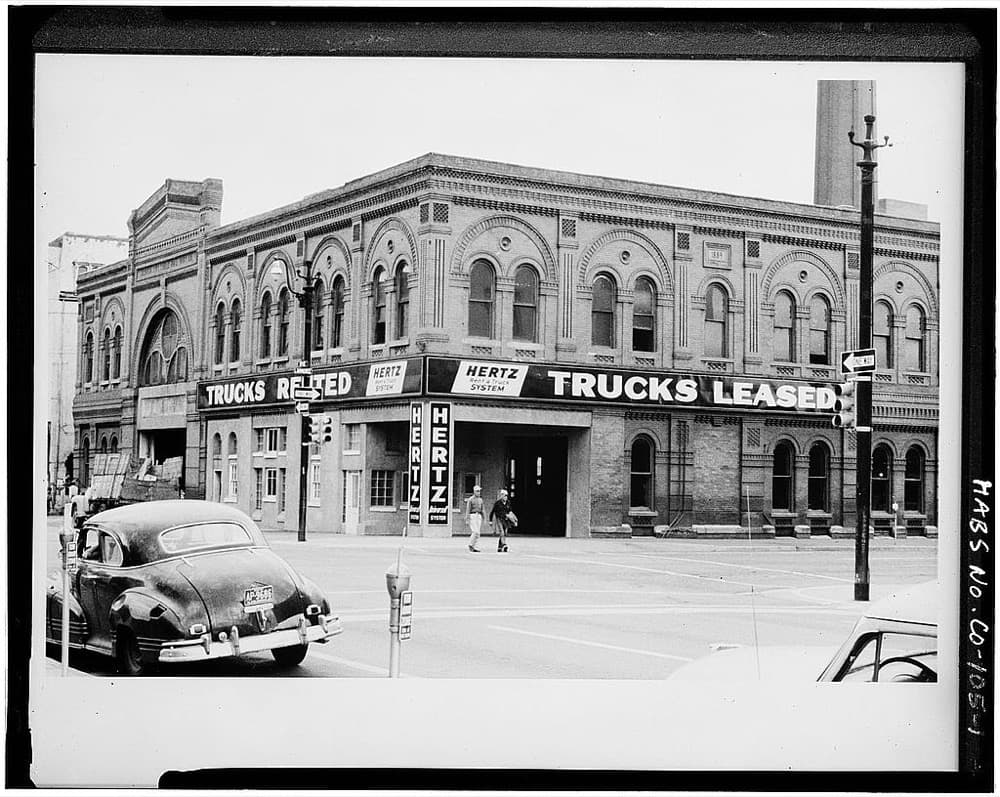

This is how coincidence and moxie saved one of the most unusual bits of downtown: the Denver City Cable Railway Building, once the wheelhouse for the network of moving cables that towed streetcars around the city.

Accidental president:

Judd in the 1970s was working as a general contractor, mostly rehabilitating small offices and industrial buildings. Historic preservation was a fairly new and novel idea, and he ran at the outskirts of the early historic circles.

"I was very busy with construction, but I said I'd help," Judd said in an interview at his home in Polo Club North this week.

The others told Judd they wanted him to be vice president of Historic Denver, a newly formed nonprofit. It'd be easy, they said -- the real work and the presidency would fall to Dana Crawford, who was garnering widespread attention for her effort to save Larimer Square from the renewal zone.

Except it didn't work out that way. Judd came home from a ski trip to this phone message from Ken Watson, another influential figure in the organization's early days: "Congratulations, President.' I said, 'Just wait a minute,'" Judd recalled.

This was his introduction to the cat-and-mouse game that the preservationists were playing with the Denver Urban Renewal Authority. This is hard to believe now, but DURA could condemn and forcibly purchase just about any property, even if there were plans to rehabilitate it.

The only thing standing in the city's way was public pressure, of which Dana Crawford had drummed up plenty for her Larimer project.

"Because of the publicity she had gathered, they were having trouble stopping her," Judd said. And the last thing that the city wanted was to have Crawford leading a full-on historical rebellion in the form of the new Historic Denver group.

So, DURA pressured Crawford to step away from the nonprofit, implying that they might allow the Larimer project to proceed if she did, according to Judd.

"That whole area was under their control. Period," Judd said. "It turned out that she had no choice. She had to give up (on leading Historic Denver) -- and I was president."

An impossible bargain:

Around the same time, Judd got a call from the owner of the Old Spaghetti Factory restaurant chain. He wanted a home in Denver, and he'd found one in the muscular brick building at 18th and Larimer streets.

It was perfect for a restaurant, the two agreed, and it was also due for demolition. DURA didn't want to hear anything about rehabilitation. (In fact, DURA's influence had already scared another contractor off the job, according to James Damis, an attorney for the restaurant.)

As accidental president of Historic Denver, Judd felt a certain obligation to press the authorities on it. He was also stinging from the demolition of Interstate Trust, a stately 1890s tower that his family had owned.

"How are we going to do it?" Judd asked of the Cable building. "We know that Urban Renewal is going to fight it."

So they started ratcheting up the pressure. Judd and colleagues convinced city council members to sign a letter in support of preservation. Damis also lobbied the council on behalf of the restaurant, and he told Denverite that the restaurant's interest was a major factor in the council's support.

DURA responded as government agencies sometimes do: by offering up a solution so impossible no one would take it. Despite having bought the building for $92,000, DURA offered to sell it for $150,000, along with an intimidating stack of warnings and requirements.

Judd knew that the walls were two feet thick and the 150-foot chimney was plenty sturdy. But nobody had the money. The bidding period came and went.

Hoping to find a last way out, Judd headed down there, stepped past the piece of plywood over the empty door frame. And then he saw it. "I looked at the damn thing, and there was no question in my mind that the bones were excellent."

Beneath the patchwork floors was an old-school but efficient system of trusses. "I figured out, I could buy it for $150,000 and put another $450,000 into it, and for $600,000 I'd have an extremely rentable building -- a beautiful building that would really enhance the city."

And now, the moxie:

The demolition company was holding off on the project, trying to give Judd some breathing room. The trouble was that Judd didn't have $150,000. He could afford half.

He brought up the project at a Historic Denver. "A fella stands up -- I had no idea who he was. 'Here's my check for $75,000'" Judd recalled.

Then there was the question of the $450,000 for renovations. "Another fella stands up, and he says, 'Well, the president of Colorado National Bank is a friend of mine -- Bruce Rockwell.'" Obviously, it paid to run in these circles.

"So, in my dirty clothes, my notes and everything, we walked into his office at the Colorado National Bank," Judd said. They explained the mission and asked for $150,000. Rockwell called his secretary over and cut a cashier's check for the full sum.

"That was the business. That's the way that we did business in those days," Judd said.

Across the street he went, into the University Building where DURA kept offices and presented the check to DURA chairman J. Robert Cameron, Judd said.

"He said, 'What’s that?'"

"I said, 'I’m buying the Cable building.'"

"Jim, you know that's already gone. The bid’s over."

So Judd asked to borrow the chairman's phone, he recalled. He announced that he was going to call a press conference, "and I think you might want to be present."

It worked. "He was dead set against it, but he wasn’t going to fight city council and the papers."

Judd soon after would get the loan for the rehabilitation. The building began its new life in 1973, though it was nearly derailed by a lightning strike just days before its opening party.

One of DURA's executives attended that party, according to Damis, the restaurant group's attorney.

"He told me that the day prior to the city council’s deadline, DURA had the wrecking ball deployed in the hope that the next morning a few swings would start the demolition. He looked around admiringly and said begrudgingly, 'Well, you guys were right. This was worth saving,'" Damis wrote in an email to Denverite.

The building today:

That bit of moxie and coincidence turned out well for Judd. After leasing it out profitably for decades, his family sold it for $7 million in 2007 to developers who planned to build two hotel towers on top of the building, which is now protected as a historic landmark.

The recession did a number on those plans, and the property sold again for $11 million in 2014. The current owner had no comment on plans for the site, and Old Spaghetti Factory remains a tenant.

The broader Skyline demolition project, of course, continued largely uninterrupted. Nothing could be done to save many of the historic buildings in Lower Downtown, or to stop the displacement of the 1,700 people who lived there.

Still, Damis credits the restaurant project and building rehabilitation for some of the new investment that followed in the surviving historic area.

"In many other cities where OSF has rehabbed old buildings in dying downtown areas, rejuvenation then occurred because other commercial ventures soon followed, which is what happened in (Larimer) Square," the lawyer wrote.

Today, it feels less likely that a project like this might happen in modern Denver -- at least not in downtown. Property costs have risen so high that small players like Judd was have few chances to buy into the market. The larger companies tend to distribute responsibilities and take fewer risks, Judd said.

"That’s the reason I stayed small," the developer said.

Have a question or a story about a unique place in Denver? Email me. Want to learn more about the city's past and future? We have a newsletter.

This story was updated on July 14, 2017 with additional details from James Damis.