By Ray Mark Rinaldi, One Good Eye

Conquering the West has always started with staking a claim, marking territory and squatting emphatically so that no one doubts ownership.

It’s an act invented, for better and worse, by the first white settlers who came here two centuries ago, and honed by generations of speculators, soldiers, miners, ranchers, railroaders and drillers, and then followed by developers who turned farms into cities and mountains into ski resorts.

The frontier has evolved, of course; it’s a gentler place in 2017, mapped, organized and easy. No one needs a horse to get around these days; most don’t even need a car anymore. But there remains a sense that things aren’t completely decided. An entrepreneur can still make a claim, like, say, inventing a new industry around cannabis or fracking, and all of the opportunities of the West seem available once again. Denver, at the center of it all, still defines itself as it goes along.

So does its foremost art museum, which has morphed and expanded along with the metropolis it calls home, and which is now assuming even more terrain with the exhibit “The Western: An Epic in Art and Film.” The show, which runs through Sept. 10, is enlightening and entertaining, and something between pop culture and fine art.

But make no mistake, this is a major move on DAM’s part, a 21st-century land grab that, if successful, seals its reputation as the pre-eminent Western art institution in the United States.

DAM — ambitiously — redefines and broadens the whole of idea of what is “Western,” connecting in one display the Western paintings of Frederic Remington and Thomas Moran; the Western literature of Owen Wister and William Cullen Bryant; the Western photography of Carleton Watkins; the Western entertainment of Buffalo Bill; the Western films of John Ford and Sergio Leone; and the neo-Western art of Ed Ruscha, Andy Warhol and Kent Monkman.

That is a long and diverse list, and to proclaim that all of those distinct genres are actually one thing is radical in its way. But this show builds a strong case for a new and holistic way of thinking about Western art, making links, appropriately for an art museum, through visuals. Curators Thomas Brent Smith and Mary Dailey Desmarais track the invention of Western images by the early painters and writers and then prove how they influenced the history and movements that came after them.

The lessons are thorough but they’re not hard. Just the opposite. Mainly because the evidence is presented via John Wayne, Clint Eastwood and the actual, red, white and blue motorcycle from “Easy Rider,” and through some of the most colorful, easy to look at paintings and illustrations ever made.

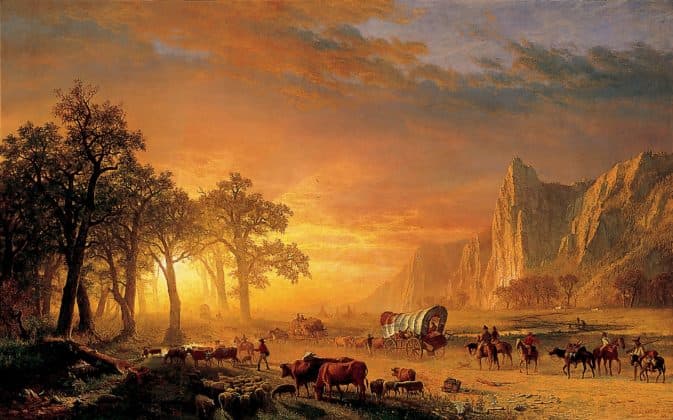

When the exhibit announces the birth of the Western visual myth, it treats us to Albert Bierstadt’s grand and glowing 1867 oil painting “Emigrants Crossing the Plains,” depicting a wagon train trekking before a glorious set of rocky peaks at sunset.

When it introduces us to iconic characters and dramas of the story, it presents Alexander Phimister Proctor’s precision-bronze sculpture “lndian Warrior,” and oil paintings, like Charles Marion Russell’s action-packed 1899 robbery scene “The Hold-Up,” and Charles Schreyvogel’s “Breaking Through the Line,” which has a Calvary soldier on horseback aiming his pistol directly at the viewer.

When it wants to link us to literature, it has, set in glass cases, major artifacts, like early printings of George Catlin’s illustrated “Letters and Notes” on Indian customs from 1832.

And when the exhibit demonstrates how these scenic ideas became movies, it shows off with excerpts of cinematic wonders, such as Edwin S. Porter’s 1903 “The Great Train Robbery,” 1952’s “High Noon” and 2007’s “No Country for Old Men.”

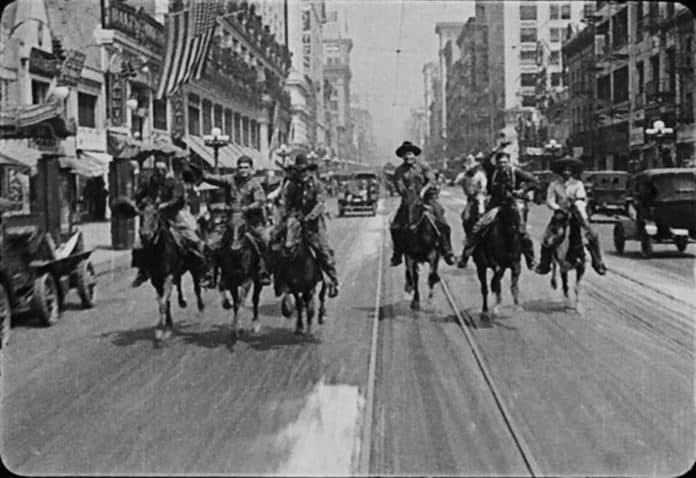

The exhibit is well-executed, both in its high-quality objects and installation. It bounces around a bit for expediency, but that lets it cover a lot of ground, and it allows for keen, convincing comparisons at several points when it directly juxtaposes two different art forms right next to each other so viewers can see what is borrowed. That happens spectacularly at the very entrance where Remington’s 1889 “A Dash for Timber” painting of cowboys on horseback stands next to a sampler reel of Western movies that stole its scenery over the next century. And it happens stunningly halfway through when it places a large, Franz Kline abstract canvas, “Palladio,” next to a still from John Ford’s film “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance.” What does a prototypical abstractionist painting have in common with a satirical Western? Both were made in 1961, both in black-and-white, and both show how, post-World War II, notions of art turned cynical, irreverent and self-obsessed.

“The Western” is the kind of exhibit you spend time with, hours even, mostly because there are lots of film clips to sit through, and they’re all compelling. The excerpts are edited down to key moments of gunfights, train robberies, field battles and bare-fisted brawls. It’s hard to turn away.

Displaying so much film is a departure for DAM, but serves as an effective way to get to the artfulness of pieces of pop culture that aren’t always taken seriously. The best thing that could happen to “spaghetti Western” film director Sergio Leone is to have a credible art museum place his works next to Remingtons. His cinematic moves are elevated here but, it turns out, not artificially.

The exhibit is less kind to the overall nature of Western art in general. From the earliest works here, like Catlin’s 1832 painting of an Indian chief, to the later looks at regional icons such as Calamity Jane, the art of the West seems trumped up and reduced for effect. It looks imagined and made-to-sell, whether the product is the art itself, the magazines and books it appeared in, or the idea of Westward expansion.

In nearly every painting and sculpture, the scenery is too perfect and the views are conveniently packaged to enhance their romantic nature; we know now that most of the West was actually flat and dusty and kind of boring. The European characters look like heroes, when actually they were Indian killers, and the Indians look like those condescending “noble savages” or like a pitiful, vanquished lot — which they were not.

The question the show raises is: Was Western art ever honest? Or was it always propaganda? Was Western life and history ever captured for anything other than its exotic qualities or to sell commercial and political ideas? The stuff could be beautiful, technically amazing and journalistic, but was it ever really art?

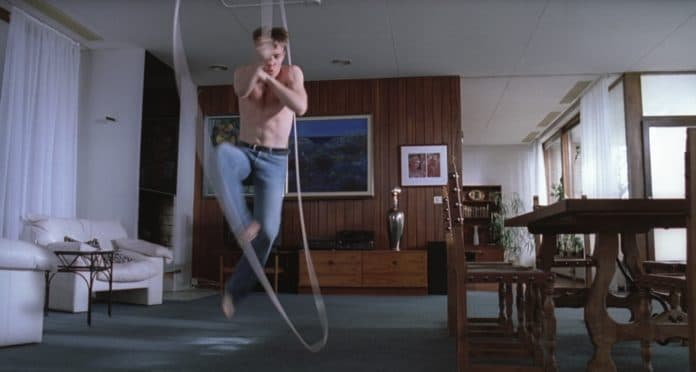

This show allows for a lot of conclusions on the part of the viewer, many negative, and that is reinforced in the final section of the exhibit, which focuses on contemporary art and film. All of the works here carry on the tradition of depicting landscape, cowboys and Indians, but nearly all of them call out the earlier Western art for its exaggerations, fabrications, sexism, racism, homophobia, nationalism and various other crimes against nature.

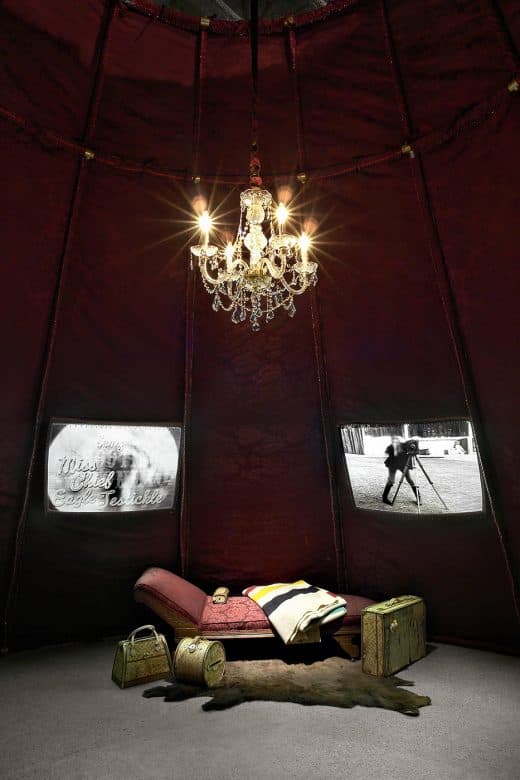

What are we to make of a piece like Gail Tremblay’s 2012 sculpture “It Was Never About Playing Cowboys and Indians,” which weaves actual 16mm film into a sort of patterned American Indian basket? Or Kent Monkman’s “Boudoir de Berdashe,” which turns a teepee into a boudoir for a fictional and exaggerated Native American drag queen, complete with mock, vintage Western films with homoerotic overtones? Or a poster from the movie “Blazing Saddles” or a clip from the campy “Thelma and Louise?”

Does all of the Western art from the last 50 years exist simply to make fun of the Western art in the 100 years that preceded it? The answer, according to this exhibit, appears to be yes — because it skipped a meaningful incorporation of later Western artists who work with the same vistas without dwelling in full parody, a spectrum that started with Georgia O’Keeffe and Ansel Adams. It is either this exhibit’s greatest strength — that it admits and accepts that baloney is at the heart of the Western genre — or its greatest weakness, undermining the concept that all of this material, strung together, is great American art.

That makes it a must-see, despite the fact that there is an extra (and anti-visitor) fee to see it.

This is a landmark show, not just because of the questions it raises, but also because it’s never been done to this degree. The whole effort, excellent catalog included, is simultaneously scholarly and a lot of fun. As a claim on expanded terrain, it appears legitimate. For residents of a city that is still reckoning how its past fits into its future, it’s an adventure.

“The Western: An Epic in Art and Film” continues through Sept. 10 at the Denver Art Museum, 100 W. 14th Ave.; $15, includes full museum admission. 720-865-5000 or denverartmuseum.org.