The sometimes hundreds of people waiting in line to pass through security at Denver International Airport represent a serious vulnerability that can't be fixed in the existing configuration of the airport's Great Hall. A major renovation planned for the main terminal would dramatically reconfigure the security screening area and open up space for a premium shopping area before passengers head off to their gates.

To make this project happen, DIA wants to enter into a 34-year, $1.8 billion agreement with a private consortium headed by Ferrovial, a Spanish giant in the transportation infrastructure world that also manages London's Heathrow Airport. The Great Hall Partners would oversee all aspects of design and construction, bring a certain amount of private financing to the table, manage the concessions, take a cut of the revenue and get reimbursed by the airport every year for expenses like debt payments and operations and maintenance.

The airport could bond for the entire project at a lower cost, but airport executives believe the deal brings enough benefits to be worth paying a premium for the financing. The greatest of those benefits are protection from cost overruns during construction and coordination among numerous contractors to keep the airport running smoothly during a complex, phased project, DIA CEO Kim Day said.

Against this argument, some community members, labor organizers, airline executives and Denver City Council members have concerns: that pay and benefits won't be as good for concessions and janitorial staff, that local businesses will get fewer opportunities, that the focus on concessions creates the wrong incentives, that potential changes to the project design could leave the city on the hook not just for change-orders now but for lost revenue to a private company for years to come.

Denver City Council was set to discuss the contract Monday, Aug. 7, but the debate was put off until a public hearing and vote scheduled for the following Monday, Aug. 14. If they don't approve the contract by Sept. 1, the city will be on the hook for a $9 million penalty to Great Hall Partners.

Here's what you need to know as this deal moves forward:

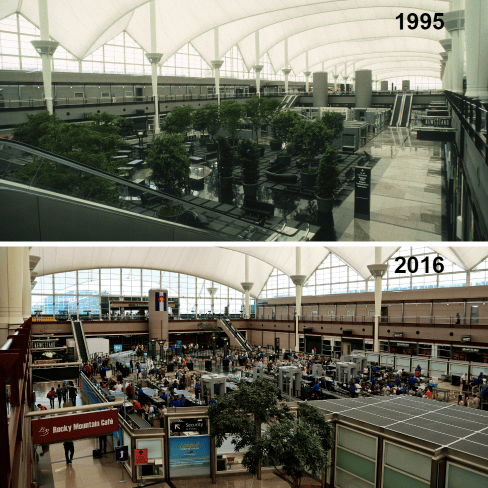

Why are we doing a major renovation on a 22-year-old airport?

The 9/11 terrorist attacks changed airport security procedures dramatically, and that changed how DIA -- designed in the early 1990s -- uses the Great Hall, the broad open space on Level 5 of the main terminal. This is where we snake through TSA security lines that cannot always be contained within the stanchions. This isn't how architects imagined this space would be used when they designed the airport.

People arriving by train or entering the airport from the Westin Hotel walk straight into the back of the security line without a convenient way to get up to ticketing and check-in. Funneling nearly all the airport passengers through a single security checkpoint means we're more prone to major delays during busy travel times.

All of this is stressful and unpleasant, but everyone's worst fear is that it could be deadly. Security experts have known and warned for some time that the most vulnerable parts of our airports are the areas before we go through security screening. That terrorists are also aware of this became very clear last year in attacks on the Istanbul and Brussels airports, as well as a Brussels subway station. More than 70 people died in those attacks and hundreds more were injured.

"If the terrorists’ goal is to cause maximum loss of life and mass casualties, the target will be the area with the greatest number of people -- whether they’re waiting to go through security inside the terminal building, or waiting to enter the airport outside the terminal building," security consultant Matthew Finn told Conde Nast Traveler in the wake of the Istanbul and Brussels attacks.

So the need to relocate security -- and make it safer and more efficient in the process -- is what's driving this project, but along the way, we're also supposed to get some really nice stores that we'll want to spend more money at.

How will this project change the airport?

There are about 70,000 square feet of space on Levels 5 and 6 that are currently vacant or "under-utilized," and both levels will be rearranged to use that space differently.

Level 6 will remain the site of ticketing and check-in, with new ticketing desk configurations that address the widespread use of self-service kiosks and other changes in how we fly. One third of the space on Level 6 will be turned over to a new security screening area designed for this purpose. The entire screening area will be protected by bullet-proof glass. Automated screening machines will allow TSA to process 250 people per lane per hour, compared to 150 per lane per hour now. Passengers will line up in special waiting areas with a couple dozen other people, instead of the hundreds of people who queue on Level 5 now.

The bridge to Concourse A will be maintained, but it won't have security screening anymore. Instead, the airport is planning services like a health club and business center.

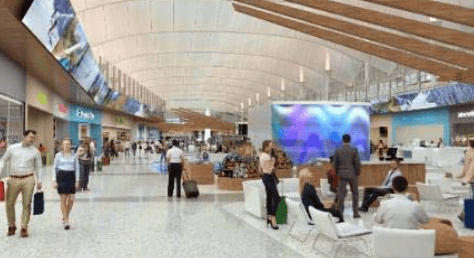

Level 5, where the current TSA checkpoint is, will be redesigned. On the south end, there will be a comfortable waiting area that airport officials compare to Union Station. This is where people arriving by train will enter the airport.

And on the north end of Level 5, there will be a similarly comfortable waiting area for greeting international flights.

Separating those two sections of Level 5 will be 35,000 square feet of concessions between security screening and the trains to the concourses. This part of the airport will be managed by Great Hall Partners, which has promised to bring a better class of concessions that will cause people to spend more money. Airport spokeswoman Stacey Stegman is careful about terminology here -- these won't be "higher end" concessions but "higher quality." The focus will be on retail shops, rather than food and drink, and the idea is to have stores that evoke our local culture.

"We know we are not an LAX or some of the European airports," Stegman said. "Our customer base is not going to come to the airport and buy a $3,000 purse, but you might have a store that sells some cool outdoor gear. We can have things that fit with the Colorado brand."

There will be lots of prominent screens with flight information so people will know if they have time to linger. If they're getting through security faster, they might have that time, and passengers with layovers might take the concourse train to shop here, too.

Will this work?

Part of me has a hard time believing in this model. It already costs a lot of money to fly, to park, to rent a car, to book a hotel. Aren't people trying to minimize what they spend on over-priced airport merchandise? But Day brings up the example of Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, where a central terminal features branches of the city's most famous seafood restaurants and stores for iconic Seattle institutions like the Sub Pop record label. I've flown through Seattle once or twice a year for the last several years, and in fact, I started looking for connections that allowed me several hours in Seattle so I could eat seafood and drink a relaxed beer. (This extra time is, of course, also my cushion against flight delays.) And I willingly take the airport train from my far-flung gate to this central terminal. I'm no high-rolling big spender, but I am doing the thing that private companies and airport planners are counting on millions of passengers doing, a few dollars at a time.

The financial modeling assumes passengers will spend about $2.50 more per "enplanement" (a word I kept hearing, confused, as "employments" until I saw it in writing) than they do now, but it adds up. Airports around the world wouldn't be going this route if it didn't look good, at least on paper, at least for now.

"Concessions bring a lot of money to the airports, so that's why we are seeing shopping malls with gates attached to them," said Rui Neiva, a policy analyst with the Eno Center for Transportation. "Ryan Air has joked that the airports should pay them for bringing people to their stores."

But Adie Tomer, a fellow at the Brookings Institution's Metropolitan Policy Program, said the value of concessions to an airport and to the local economy can be overrated.

"Nobody says, 'Oh, I was going to visit family in Milwaukee, but instead I’m going to fly to the Emirates to go shopping,'" he said. "It doesn’t pass any kind of logical test. I mean, yes, as long as we have you trapped here, let’s extract as much value as possible. That makes sense. And it’s also important to maintaining competitiveness."

Concessions revenue is a major part of the deal with Great Hall Partners.

- The renovation of the Great Hall will cost an estimated $650 million.

- The airport itself will put up $480 million, while Great Hall Partners -- a consortium made up of Ferrovial, Saunders Concessions, a subsidiary of Denver-based Saunders Construction, and Magic Johnson Enterprises/Loop Capital -- will put up $170 million.

- The Level 6 changes -- the new ticketing and security area -- will cost about $175 million, while $298 million will go toward terminal operations and passenger circulation and another $177 million will go into the concessions area.

- The airport has set aside $120 million as an "owner's contingency" to pay for changes it asks for during design and construction. These might be changes to accommodate new security procedures or airline operations. With the contingency, the total project cost should be capped at $770 million.

- Great Hall Partners is also putting up money for long-term maintenance needs, for a total private investment of $378 million.

- Great Hall Partners will manage the concessions and take 20 percent of the revenue, while the airport will get 80 percent of the revenue.

- The airport will also pay $24 million a year to Great Hall Partners -- $9 million to offset operations and maintenance in the concessions area and $15 million to offset Great Hall Partner's financing costs. Those supplemental costs are indexed and will increase over time. Over the 30-year term of the deal, the airport will pay $1.2 billion to Great Hall Partners in O&M and capital costs.

- Total payments to Great Hall Partners, from construction to the end of the deal, are capped at $1.8 billion.

The deal assumes Great Hall Partners will get a 10.8 percent return on investment, with the airport guaranteeing 4.8 percent and the remaining 6 percent coming from how well Great Hall Partners can manage the concessions and how much profit they can extract. That 4.8 percent represents a premium that DIA is paying for the money Great Hall Partners is bringing to the table. If the airport were to bond for that same money, it likely would be paying an interest rate between 3.5 percent and 4 percent, Stegman said.

The airport estimates about $519 million in revenue over the 30-year term, which is less than the $770 million in supplemental payments the airport expects to make to Great Hall Partners. However, the airport would get additional revenue from advertising and keep 100 percent of the revenue from tenants on the bridge to Concourse A, Stegman said. Stegman also noted that the airport would incur a range of costs associated with managing and maintaining that area if Great Hall Partners weren't in the deal at all.

DIA has the bonding capacity to do this project without a private partner, so why pay the premium?

It's all about risk management, airport officials say.

Consider the example of the Westin Hotel and the transit center where the A Line arrives at the airport. That project had a budget of $500 million, but an independent audit at the end of construction found the actual cost came in at $720 million. There wasn't even any mismanagement alleged; things just happened.

For airport executives and for the city officials who support this deal, that's one of the risks that a development agreement with Great Hall Partners would guard against. Great Hall Partners pledges to bring the project in on time and at cost. If there are cost overruns, Great Hall Partners absorb those, and if there are significant delays, it would be considered a default.

"My math shows me that over time you pay less," said Council President Albus Brooks, comparing the Westin Hotel project with the Great Hall proposal. "There were three organizations involved in the hotel development, we saw a number of change orders and the number just kept escalating. ... That is what a lot of folks are missing in this deal."

The Great Hall project will also involve numerous contractors and subcontractors and complex staging in order to keep the airport running smoothly. Having one entity managing all that makes sense to airport officials.

But how much risk is Great Hall Partners really taking on?

Construction is just part of the deal, and the agreement is built around all sorts of assumptions about future traffic numbers in the airport and how much people are likely to spend. If the city does something that causes those numbers to change in the future -- like changing the flow of traffic so people didn't go through the concessions area or improving the concessions in the concourses in ways that compete with the Great Hall -- Great Hall Partners would be able to make a claim and ask for compensation.

These "compensation events" are a major source of concern for some council members, particularly because there's already some indication the project design might change.

The airlines that use DIA are concerned that waiting passengers could spill out of the new security area into ticketing and check-in on Level 6 and turn that part of the terminal into a snarled mess. United President Scott Kirby told the City Council and later repeated to me that he believes the current design was driven by a desire to maximize concession space at the expense of airport operations, and that this misplaced financial incentive made for a bad deal. The airlines have asked for a 120-day delay in approving the contract.

DIA and the airlines are in talks, but some council members are concerned that whatever solution they work out will result not just in change orders right out of the gate but long-term payments to Great Hall Partners.

"If we impact the quantity of concession spaces, we could not just be paying for the increased construction costs, we would be paying for the lost concession space for the 34-year term if we do this after we sign the contract," Councilwoman At-large Robin Kniech said. "If we make the change before we sign the contract, we might avoid that."

Stegman downplayed the possibility that a change in the Level 6 design will affect concession space, which is mostly on Level 5. But this is just the conflict over space in the airport that we know about now. Councilman Rafael Espinoza pointed out the city is entering a 34-year deal to fix a 22-year-old airport.

"We know the main terminal and how it’s functioned has changed quite a bit," he said. "My guess is that in a 30-year term, the world will change a couple times."

That's not the only concern with this deal.

The reaction from different sectors of labor and business could be seen as a microcosm of the rest of the economy.

Howard Arnold, president of the Colorado Building and Construction Trades Council, which represents unions from the mechanical, electrical and piping trades, urged City Council to approve the deal.

"This project will put thousands of construction workers to work over the course of the four years it takes to build this project," he said. "These are jobs that will come with a five-year apprenticeship and continuing training after the apprenticeship is over. It provides a career for people for the rest of their lives. ... This is a project that will put bread on the table for hundreds of families who work in the craft trades."

But Unite Here, a union that represents concessions and hospitality workers, including some 500 workers at DIA, doesn't see the same benefits for their members. The people who work in stores and restaurants in the Great Hall now will lose their jobs as those businesses close for construction. They have no guarantee of jobs in the new Great Hall, and Unite Here members are concerned new jobs won't have the same pay and benefits. The contract does not include a "labor peace agreement" -- an accord under which workers agree not to strike in exchange for business not opposing a unionization campaign. One way private companies save money over the public sector is skimping on wages and benefits.

Councilman Paul López is generally on board with the proposal and the contract -- except for this issue.

"I believe it’s a good deal if it’s a good deal for everyone, from folks working on the tarmac to folks handling baggage to the pilots, down to the people mopping the floors and making Denver’s airport as clean as we like to brag on," López said. "We have the cleanest airport, and that doesn’t happen magically."

On the business front, Brooks is excited about opportunities for local, minority-owned businesses to get slots at the airport, while others are more skeptical. The contract with Great Hall Partners carries over many protections that are part of city contracting but normally absent in the private sector, including requirements to have a certain number of women- and minority-owned businesses.

"The other thing no one is talking about -- and I am extremely excited about it -- for the first time in Denver history, we have an African-American investor who is famous involved, who is well known for bringing minority contractors on board," Brooks said of basketball star Magic Johnson's participation. "... He made some bold commitments that I will not let him forget."

Veronica Barela of the Committee for City and Airport Fairness (and a long-time West Side organizer) said the power that Ferrovial has over concessions could shut out smaller businesses that can't generate as much revenue, and Councilwoman At-large Deborah Ortega said many local businesses won't be able to afford to build out the spaces inside the airport.

Is this a good deal?

This is, of course, the $1.8 billion question. Airport officials answer it with a resounding YES.

"We have a vulnerability that exists today, that is obvious to anyone, that we cannot continue to let be," Stegman said. "We have an opportunity to make the security screening process better and safer and more efficient using new technology. Additionally, this frees up an opportunity to address things that we’ve been hearing from customers that they want -- more concessions, better seating -- so this airport can grow into the future in a more flexible and more dynamic way."

So do some council members.

"A plan has arrived," Brooks said. "Let's create opportunities for businesses, for local business, let's improve the infrastructure, let's transform the entire Great Hall. I am very much supportive of this plan."

I talked to people who study similar "P3" deals -- public-private partnerships -- and follow airport trends. Without access to a detailed financial analysis, they said they couldn't give a thumbs up or down to this deal, but they said skeptical council members are asking the right questions.

Neiva, the policy analyst with the Eno Center, said allocation of risk is the primary issue in the P3 deals that are becoming common as airports try to stay on top of changes in the industry.

"That's always a problem in public-private partnerships, how you spread risk with the private sector, because they are only in it for the money, and they want to have as little risk as possible," he said.

The detailed financial modeling behind the deal is considered proprietary. Airport officials have made it available for review to the city's auditor, to the city's chief financial officer and to council members, who can review it in an office and ask questions there. But Ortega expressed frustration with this set-up, saying you must have expertise to know what you're looking for, and she needs time to sit with the numbers before making a decision. She sent a letter to Day, DIA's CEO, with detailed questions about risks, responsibilities and what recourse the city will have if Great Hall Partners doesn't follow through on contract requirements, and in an interview, she said she hasn't been satisfied with the answers she's received so far.

"Everybody is going to make money on this deal, but it doesn’t look like Denver is making the kind of money it would need to," she said. "Where is the revenue that we’re getting if we’re just turning around and handing it over to them?"

"The risk is really not that great to Ferrovial," she continued. "The risk is greater to the city because we’re at 30 percent design, we don’t have the airline issue resolved and the language is very clear around the compensation events. Anything that is not already clearly defined in this agreement that results in a change is the responsibility of the city."

A spokeswoman for City Auditor Tim O'Brien said the office is reviewing the financials and the contract to make sure everything is legal and adds up, but it's not the auditor's role to set policy -- and this contract is ultimately a policy decision.

Unite Here did its own analysis of the deal and in a letter to City Council, Ian Mikusko, director of the union's Airport Group, estimated it will cost the airport $350 million more than publicly financing the project. Stegman countered that the analysis was simplistic and didn't take into account cash flow issues, risk management and additional revenue opportunities. But Mikusko said it's a problem that an analysis based on the publicly available numbers doesn't make a strong case. The public needs more information to assess the deal, he said.

Peter Kirsch, an attorney who works on transportation infrastructure deals and who has represented DIA in other projects, said "Is this a good deal?" is kind of a naive question.

"Don't tell me your views until you tell me what your objectives are," he said. Critics might say that DIA isn't getting the most money out of the deal, but "maybe they weren't looking for a good money deal. Maybe they wanted someone else to manage it. Maybe they don't want the headache of operating the terminal. ... At the end of the day, is Denver getting the pieces out of the equation that they want?"

This story has been updated to reflect that council debate was put off until Aug. 14.