The decision to give Denver its own department of transportation back in July was more of a squeaker than you might've thought.

On Wednesday, Denver's Chief Performance Officer David Edinger shared some results of the six-week study that Denver conducted with the City Council Mobility Task Force.

So here's how the decision was made:

Relatively quickly, for starters. The study lasted six weeks from the end of April to early June.

That's because at the time, the city was interested in putting the question of a new department of transportation to Denver voters this November. (Because the city wants to create a cabinet-level department, voters would have to sign off on the decision through an amendment to the city charter.)

Since then, the city has decided to take it a little slower. For one, Denver Public Works needs a new executive director before the process can begin.

Another reason is that other cities interviewed for the study said creating a separate DOT is a really difficult and time-consuming process. And in the case of Oakland, the decision to separate mobility issues from their traditional domain of Public Works may have set the city's mobility agenda back, Edinger said.

"By spending so much of the time trying to do it so fast, perhaps they had created some disruption that they could've avoided," he said. "The mayor (of Oakland) campaigned on creating a separate DOT and had to almost immediately upon taking office form that DOT. "

Separating the existing Denver Public Works into people who work on mobility and people who work on everything else could take as long as 12 to 24 months. And it's a big chunk of people too -- Edinger estimated that between 500 and 600 of DPW's existing employees work on mobility issues.

Then, those people have to transition to a new department, which could take another 12 months.

So why bother with all the hassle anyway?

Well, four out of the seven cities interviewed for the study said that creating a separate DOT helped the city be more effective at delivering on mobility goals. For Charlotte, a separate DOT allowed the city to more clearly organize its efforts. Two more cities said it might've helped.

Plus, an analysis of almost 80 transportation and mobility issues pushed the city in that direction.

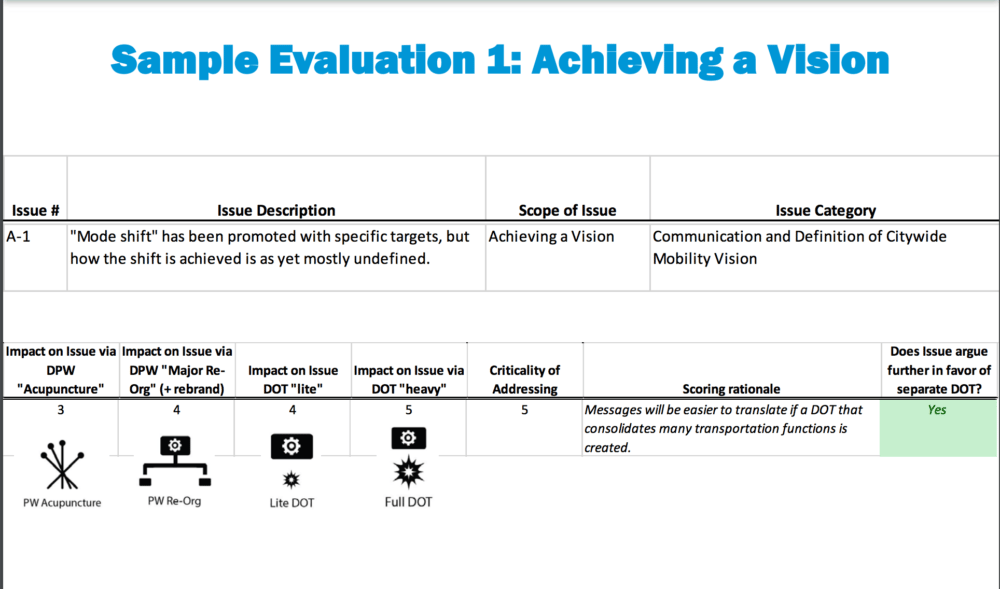

Consultants took each issue and decided whether a new DOT could help that issue based on interviews with DPW employees, RTD and more. The consultants also scored whether other options, like reorganizing DPW, would help the issue. Each option gets a score from 1 to 5, and a 5 means that the new organization would be a major improvement.

Here's an example:

"Mode shift", or getting people to use something other than a single-occupant vehicle, is most improved if the city decides to implement a full DOT, as evidenced by its 5 score. It's also one of the city's most important issues, scoring a 5 for "criticality of addressing."

So all 80 issues get a score, and the average scores showed that either reorganizing DPW or creating a full DOT were the best options. Creating a full DOT scored slightly better, but Edinger called their scores "practically a tie."

Then they looked at whether or not each of the 80 issues argued in favor of a separate DOT or not. (This was a yes or no answer, assigned by the consultants.)

Again, the results were mixed in some regards. In a raw numerical sense, 69% of the issues didn't "argue for a separate DOT." But ultimately, the city's most important issues were better served by a separate DOT, according to the study's results.

And so the decision was made to split. But it was more than numerically close:

"I think there were a number of folks on the project team that felt like the disruption was not worth it, and we could follow the Minneapolis model of keeping it all together," Edinger said. "But ultimately the decision was made to split."