Denver's police officers are rarely arresting homeless people under the city's "camping ban" — but the city is increasingly using another law that forces people to move along, according to a new report from the University of Denver.

In 2013, police reported that they had issued 1,349 citations for trespassing to people experiencing homelessness. By 2017, that figure had grown to 1,765.

The numbers show that police are enforcing trespassing laws more often in order to push away unwanted people, according to Ray Lyall, a member of Denver Homeless Out Loud.

"That's an easier ticket to give. They just pass around trespass tickets," he told Denverite.

But city staff say that police officers have little choice in the matter, and they pointed out that arrests under other homeless-related laws have stayed largely stable.

There are a few possible explanations.

Trespassing means someone was present where they weren't allowed, including private land -- such as vacant lots -- and certain restricted public areas.

Denver's population has grown significantly in the last few years, but the DU report shows that the increase in trespassing warnings has largely gone to homeless people. In 2017, nearly 60 percent of all trespassing citations went to people experiencing homelessness, an increase from about 54 percent in 2014.

Police often give warnings before resorting to a ticket or arrest, but some recipients say it's pointless to comply. "They gave me several warnings. I needed a place to sleep," Lyall said.

It's also possible that the increase in trespassing is related to an increase in homelessness. Numbers on homelessness are notoriously unreliable, but an annual survey finds that chronic homelessness has grown steadily here in the 2010s.

City spokespeople said that police were simply responding to property owner requests.

"If a person is trespassing and a property owner calls it in, Denver has a duty to enforce the violation. We cannot selectively enforce this based on whether the person is experiencing homelessness or is housed," said Sonny Jackson and Julie Smith, spokespeople for the Denver Police Department and Denver Human Services, in a joint statement.

They did not immediately respond to a question about why the trespassing figures are increasing, but they pointed out that arrests under other homeless-related laws have declined or stayed stable in the last few years.

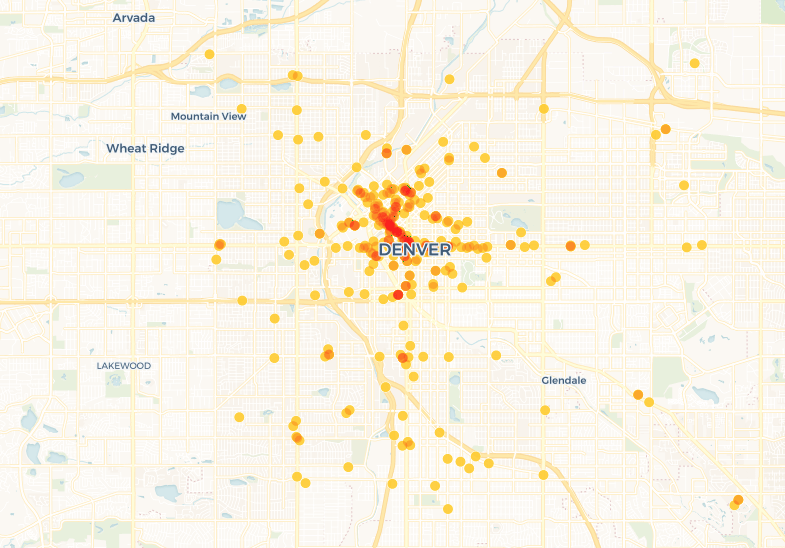

The map above shows where police cited people who had "no fixed address" under laws such as trespassing, public urination and panhandling, along with 12 others identified by the DU team.

The 16th Street Mall and Colfax Avenue both saw high concentrations of enforcement.

Sandra, who declined to give her last name, said that she and others had moved out of Denver to avoid police and parks rangers, fleeing instead to a vacant patch of woods beyond the county line.

"We were able to camp right outside the Denver border with Adams County. I was there for two or three months," she said. Others are going to Federal Heights, Englewood and other suburbs, according to Amanda Lyall, a resident of Denver's tiny-home village.

The net effect, according to professor Nantiya Ruan, who oversaw the DU research project, is that people are moving into less-safe places.

"They get pushed off of well-lit, well-trafficked, policed areas to places that are more uninhabitable, that are more dangerous, that don’t have good light — especially if you're an individual or a woman," she said. "They get pushed out of the business districts."

Jason Flores-Williams is an attorney leading a class-action lawsuit against Denver on behalf of homeless plaintiffs. The trespassing statistics strengthen his argument, he said, that the city has "a class of homeless people, and the city has targeted them to move out of the city."

While the laws seem OK on their face, they're being applied "in a disproportionate way," he said.

What does this mean for the camping ban?

One of Mayor Michael Hancock's first major actions in office was to implement a "camping ban," which forbids people from using blankets, tents, tarps and other cover when they're sleeping on public property in Denver.

But the new law is rarely enforced to its fullest. The DU data shows that police only cited five people under the camping ban in 2017.

Instead, officers take a lighter touch. Police reported nearly 5,000 instances where they warned or contacted someone about "unauthorized camping" in 2017. Those numbers include instances where officers were offering food and shelter, according to city staff, but the DU paper claims that they often are meant to move people along.

Meanwhile, the city is pushing to expand its homelessness services, including through its investment of more than $4.5 million to buy property for a new shelter in northeastern Denver, plus $3 million more to replace the roof, update HVAC equipment and outfit bathrooms at the facility.

"Denver’s multi-faceted approach to addressing homelessness is making a difference in the lives of our residents. We have housed thousands of people, have helped thousands more avoid the loss of their home through eviction support, have increased the number of shelter beds and have improved the quality of services," Smith and Jackson wrote.