The people of south Denver are pretty fired up.

They turn out by the hundreds for community meetings, many of them demanding sidewalks, restaurants and other amenities that often are missing in older neighborhoods far from the city's center.

This year, though, they took a blow -- and the story of one piece of property illustrates some of the biggest challenges to reinventing places like Hampden Avenue or Colorado Boulevard.

So, here's what didn't happen.

Councilwoman Kendra Black has been pitching an idea called "Parkside" to just about everyone who will listen. She first told me about it during a lively tour of her district.

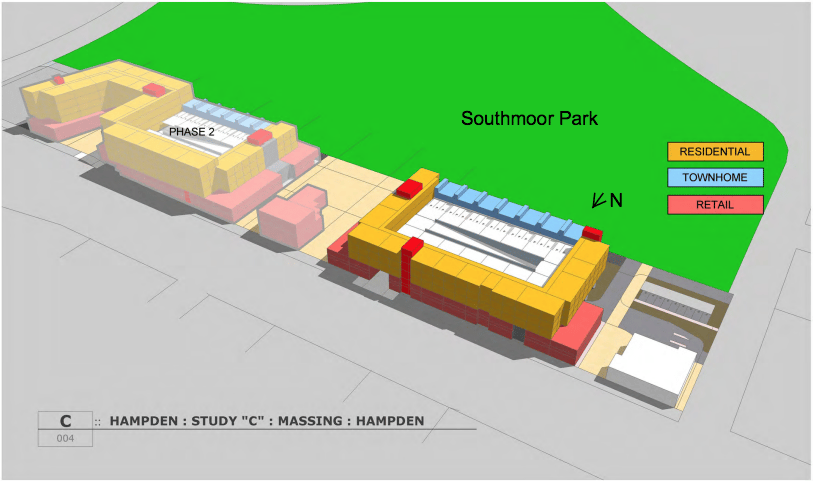

Basically, she wanted developers to design their buildings around one of her district's parks. Right now, Southmoor Park is bordered to the north with pretty typical stuff -- a Walgreens, a bank, a ton of parking -- and all of it faces toward busy Hampden Avenue, ignoring the park's green space.

"How cool would it be to orient a beer garden toward the park?" Black asked. The city even hired RNL Design in 2016 to lay out a vision for a "dynamic 24/7 retail/dining experience," with townhomes and a plaza facing the park.

But that vision has suffered a pretty big setback: One of the current owners recently sold a key piece of property to Portercare Adventist Health for nearly $2 million.

Instead of a millennial-magnet beer garden or a mixed-use development, the corner of Oneida and Hampden will likely be home to a bank and a Centura Health freestanding emergency room. You can debate the benefits of freestanding ERs, but they definitely are not a component of a fun night out.

At a recent council meeting, residents got so mad about the idea that they started booing, according to Black and others.

"I think what worries me is that developers have the wrong idea about southeast Denver and what southeast Denver residents want," said Aylene McCallum, a neighborhood resident. "And when they’ve been told what they want, they ignore it."

But, at this point, there's little that Black and her neighbors can do to slow down the medical facility.

The project won't require city council approval, Black said. And city officials already have received paperwork for the two-story, 25,000-square foot medical facility. It would cover about 17 percent of its lot and come with 100 parking spaces when it's completed in 2019, according to paperwork.

"I’ve been having all these meetings trying to get the community engaged," Black said. "Instead, we’re just going to have a big, ugly building surrounded by asphalt."

For Centura's part, a spokesperson said that the emergency room would serve the area "by providing convenient, accessible health care services."

Let's put this in context.

Joe Vostrejs, a developer and the owner of Lowry Beer Hall, was part of the group trying to put together the Parkside deal.

"I would have loved to have seen a way to create a retail environment that would have really addressed the park and created some amenities for the park, more of a pedestrian kind of experience," he said.

The major problem, here and all over suburbia, is that the property is just too expensive -- and it's made even more expensive by the fact that it's covered in suburban-style buildings that add to the cost.

"I think there’s a lot of parts of Denver and the 'burbs where you run into that problem," Vostrejs said.

"You have existing improvements that may not be ideal, but they still have significant enough value that trying to justify tearing them down, so that you can get back to dirt, so that you can create something more desirable — the math doesn’t work."

But you know who can afford it? Walgreens, chain restaurants and hospitals.

"Those kinds of companies ... they decide, demographic-wise, where they want to be," said Phil Yeddis, executive vice president of Unique Properties. "They pay whatever it costs, because they’re going to be there long term."

Chrissy Nicholson, a spokesperson for Centura, said that the company's market analysis had shown population growth and growing demand for health services in the area. There's a lack of primary care and emergency services in the area, she wrote in an email.

Smaller businesses have a real rent problem in Denver.

This isn't just a problem for would-be developers. Rent is climbing in commercial spaces across Denver -- and the effect is just as strong in the outer parts of the city, where there's relatively little new development, according to Yeddis.

"Because there isn’t any new construction, rent’s going up," he said. "That’s displacing people. A lot of people are going out of businesses."

And the effect is especially painful for smaller businesses.

"On places like South Colorado Boulevard, Hampden, real estate is actually really expensive," Vostrejs said. "You’re competing with banks and cell phone stores that can pay really high rents, or chains."

In places like Southmoor, that means that retail tends toward the standard suburban stuff. They still have some consumer amenities, like a Whole Foods, but residents complain that the options are limited.

"I have to drive everywhere for any kind of entertainment and shopping," said Rebecca Winslow, president of Southmoor Elementary's PTO.

Meanwhile, in southwest Denver, Councilman Kevin Flynn has said that he's facing "inner ring decay." Restaurants and even some larger retailers, like grocery stores and a Target, have departed for other cities, only to be replaced by 99-cent stores and other businesses that are perceived as less desirable.

"We have been losing commercial, neighborhood-serving commercial for probably the last 10, 15 years," Flynn said in an interview earlier this year.

That's happening in part because businesses and developers are chasing wealthier customers to the city center and out to faster-growing suburbs, Yaddis said.

That would logically create some vacancies for smaller businesses -- but landlords in some cases are holding out for higher rents from the freestanding ERs and Walgreens of the world. There's also the fact that low-density residential areas simply aren't appealing to restaurants that are used to the constant crowds of downtown.

What would change this?

Did Kendra Black's beer garden ever have a chance? Well, it was a long shot.

"The hurdles to local independents -- finding good real estate at the right price, and then being able to do an adequate amount of business to be successful -- can really set up some roadblocks," Vostrejs said.

But he was confident that Hampden Avenue could have supported the dream of something different, and he's still interested in south Denver. And there are already some bright spots, including the plan to create a food hall at Happy Canyon.

And one possibility jumped out as Vostrejs and I talked: the office buildings along south Denver's boulevards. Their vacancy rates are climbing, he said. On Hampden, some office spaces are even renting their lots out to car dealers.

"Maybe that’s a good thing," Vostrejs said. "Maybe that’ll help prompt the redevelopment of some of these buildings to more attractive uses."

Councilwoman Black wants the city to ramp up its planning efforts in south Denver as soon as possible.

"I feel very strongly that community planning and development needs to listen to my constituents and come down and help us," she said, "so we don’t get more used car dealerships and dollar stores and tire stores and massage therapy places."

In fact, the city is in the middle of a new neighborhood planning initiative. It will take 13 years to cover the entire city, and the planning department hasn't yet announced when the south and southeast will get their turn.