New science standards adopted by a divided Colorado State Board of Education call on students to learn by puzzling through problems in the natural world rather than by listening to facts from a teacher.

The new standards, largely based on Next Generation Science Standards already in use in whole or in part in 38 states, represent the most significant change to what Colorado students will be expected to know in this round of revisions to state standards.

The State Board of Education reviews academic standards every six years. That process concluded Wednesday with the adoption of standards in comprehensive health and physical education, reading, writing and communicating, and science. The board had previously adopted new standards in social studies, math, world languages, arts, and computer science, among others. Most of those changes were considered relatively minor.

The new science standards, which were developed based on years of research into how people learn science, are considered a major change. They focus more on using scientific methods of inquiry than on memorization. In a time when we can look up literally any fact on our phones – and when scientific knowledge continues to evolve – supporters of the approach say it’s more important for students to understand how scientists reach conclusions and how to assess information for themselves than it is for them to know the periodic table by heart.

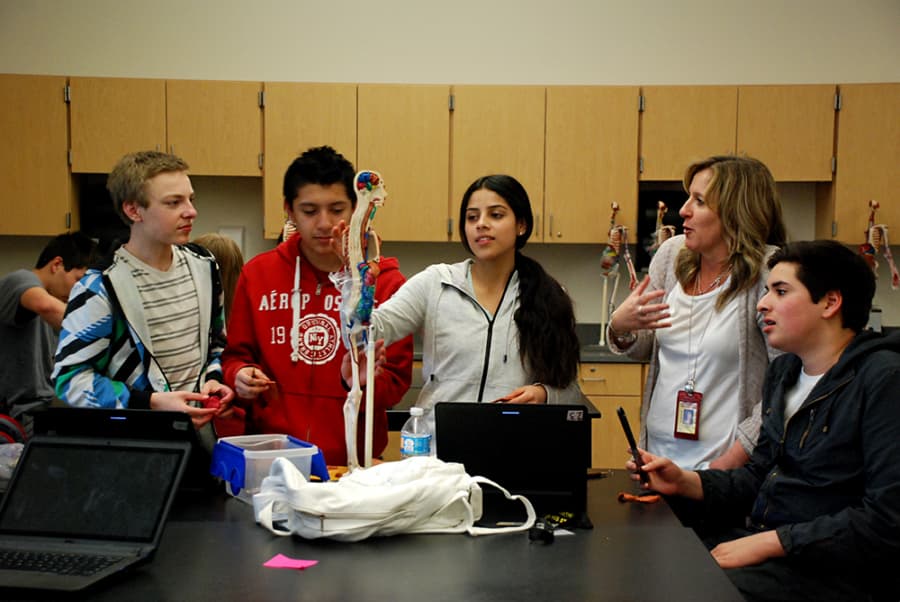

Melissa Campanella, a Denver science teacher, is already using Next Generation-based standards in her classroom. Earlier this year, she described a lesson on particle collisions as an example.

In the past, she would have given a lecture on the relevant principles, then handed her students a step-by-step lab exercise to illustrate it. Now, she starts the same lesson by activating glow sticks, one in hot water, the other in cold. Students make observations and try to figure out what might be behind the differences. Only after sharing their ideas with each other would they read about the collision model of reactions and revise their own models.

Supporters of this approach say students learn the necessary facts about science along the way and understand and retain the material better.

Critics fear that not all classroom teachers will be capable of delivering the “aha” moments and that students could miss out on critical information that would prepare them for more advanced study.

That fear was one reason all three Republican members of the state board voted no on the new standards. They also disliked the way the standards treated climate change as a real phenomenon. Nationally, the standards have drawn opposition from religious and cultural conservatives over climate change, evolution, and even the age of the earth.

Some Democratic members of the board started out as skeptics but were won over by the overwhelming support for the new standards that they heard from science teachers.

Board member Jane Goff, a Democrat who represents the northwest suburbs of Denver, said no one she talked to in her district wanted to keep the old standards.

“Most people expressed outright that they felt comfortable with the amount of resources they have (for implementation), and they were enthused about the possibilities presented here,” she said.

Under Colorado’s system of local control, school districts will continue to set their own curriculum – and that’s one point of ongoing concern even for board members who support the change. The state has very limited authority over implementation.

“If we were a state where we had more control over curriculum, some of those concerns would not be so great that students might not learn certain material,” said board chair Angelika Schroeder, a Boulder Democrat.

Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools.