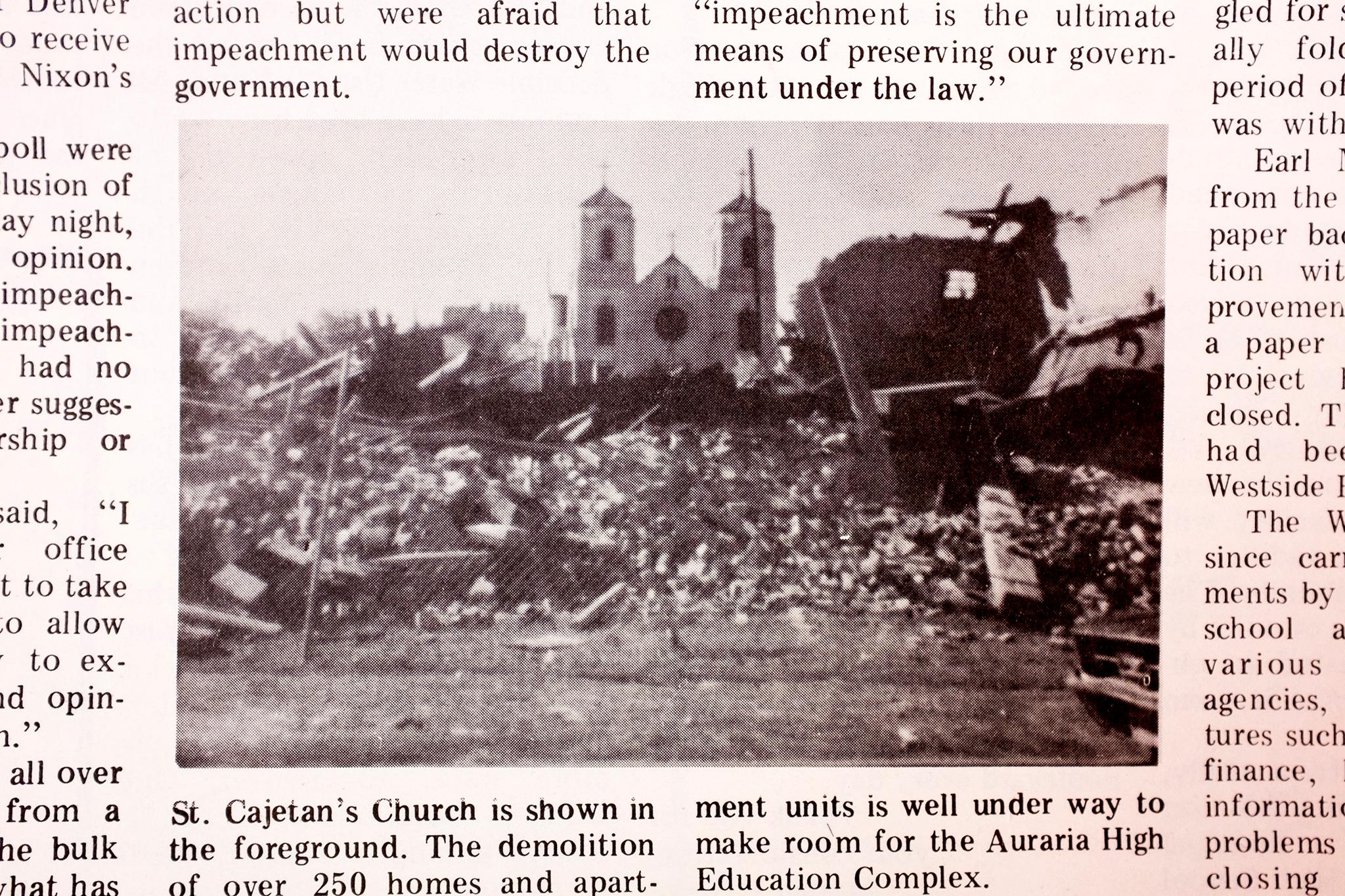

Virginia Castro was never interested in politics before the plan to develop Denver’s Auraria campus started to pick up steam. The neighborhood that once sat in that little triangle of land was Denver’s oldest and had become dense with Latino families who in the late '70s were suddenly facing the possibility that they’d be pushed out of their homes to make way for the project. It wasn’t long before Castro was swept up in a tidal wave of activism.

It was the beginning of a fight to preserve that community, which at the time was seen as inseparable from La Alma-Lincoln Park to the south. The ensuing struggle helped launch the Chicano movement in Denver, which expanded to take on many issues beyond displacement and became entrenched on Santa Fe Drive. Those activists made themselves known through civil disobedience, parades and art, exercised in the name of establishing their culture in a very public way. While Auraria was eventually scraped, they successfully made a home on the west side, for a time. Their efforts set the stage for the vibrant arts scene that exists today and helped make Santa Fe Drive desirable for the booming development that’s beginning to mature.

Fear of displacement galvanized a new political force in Denver.

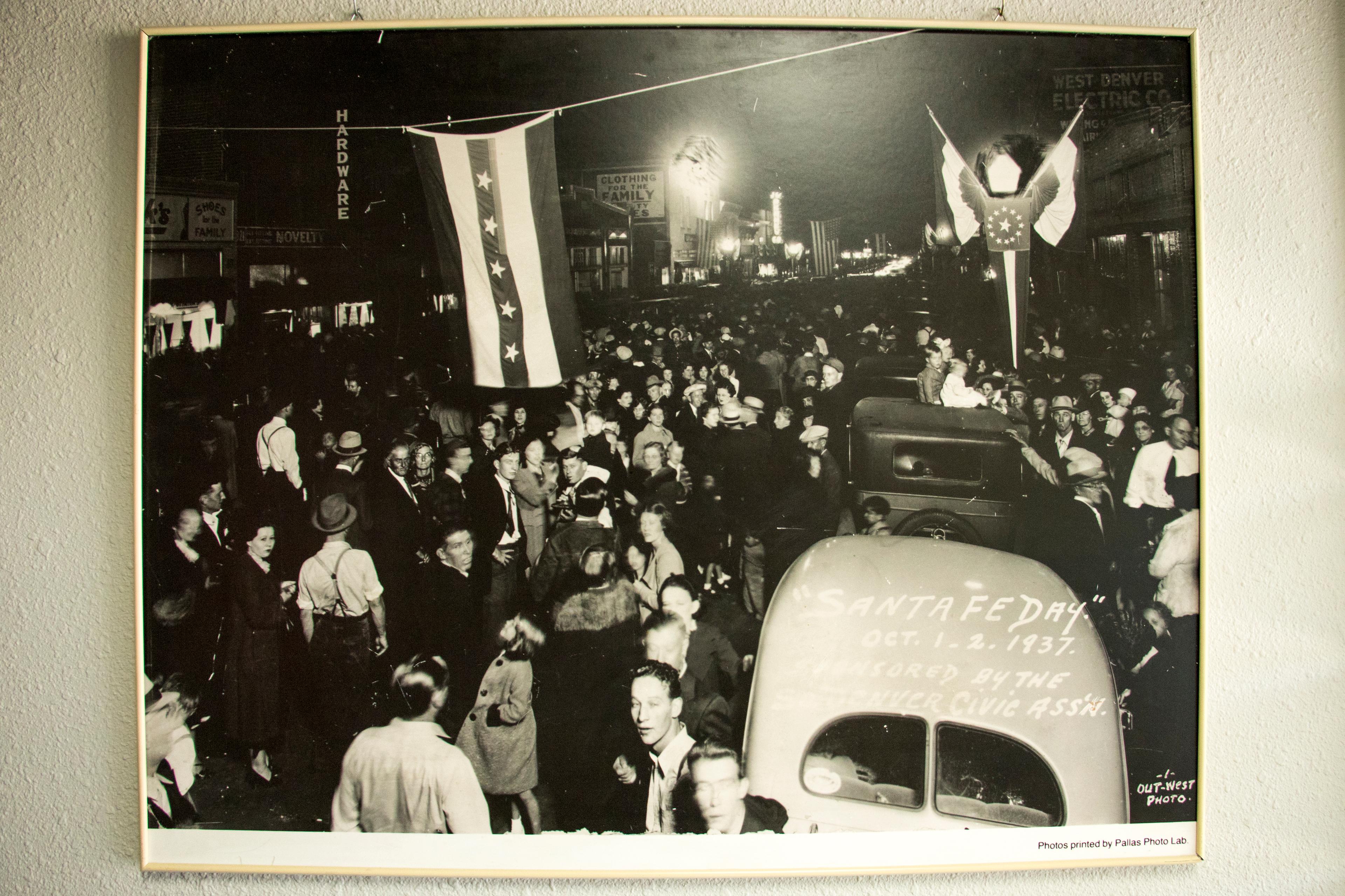

After gold beckoned settlers to Colorado, a railroad was constructed through Denver that established La Alma-Lincoln Park and Auraria as the city’s oldest neighborhoods. For at least a half a century, that iron vein attracted all kinds. It was diverse with immigrants and pioneers of all stripes until "white flight" pulled white families to the suburbs. By the 1950s, the area had undergone a demographic flip, and Latino families became the majority residents in what became known as the west side.

Castro began her freshman year at Metro State University in 1976. At the time, the school had no centralized campus; instead, students met in scattered buildings around Civic Center.

“One day we had some people from the student government come to us and talk about this bond issue that absolutely had to be passed,” she said, “Metro needed a campus.”

The plans to reshape Auraria were also, in part, triggered by a massive flood in 1965 that prompted a rash of projects throughout the city.

It wasn’t long, maybe a week later, that west side representatives made their own visit. They feared that Auraria’s redevelopment would decimate the community there, and they saw consequences for neighbors along Santa Fe Drive. Latino students began to organize against the bond measure, and by her sophomore year, Castro had joined their ranks.

“The organizers of the neighborhood were trying to instill into the people that this is serious. This could mean changes that you can’t even believe,” she said. “It wasn’t just being students at a school anymore,” and her life changed forever.

She began devoting more time to the cause than her studies. She met Richard Castro, a future state Speaker of the House who would become her husband, and together they fought for Auraria.

“It just seemed really important,” she said. “By that time the movement was in full swing."

Castro said she didn’t realize that Latino students and activists were organizing all over the county. In hindsight, she now sees she was a part of a “collective unconscious” political awakening across the nation. As those efforts coalesced in Denver, the word Chicano and the movement around it were really first being defined, and leaders like Corky Gonzales and Cesar Chavez were emerging. In 1969, Castro and her cohort formed the West Side Coalition to focus their efforts.

Despite their labor, eventually, “they got beat in the bond issue,” said Ramon Del Castillo, a Chicano activist who helped Chavez lead a lettuce workers boycott in Greeley and would become a professor of Chicano studies at Metro State years later. Even though they lost that first fight, he said, people like him and Castro were already past the point of no return.

The movement did not die with the Auraria neighborhood.

Instead, the coalition set up a headquarters on Santa Fe at Sixth Avenue and established the street as a centerpiece of their movement.

“This was our street,” Castro said.

The movement was further solidified by Corky Gonzales. Though he became a controversial figure in the city, Castillo said he granted the movement an identity and challenged its activists to reclaim their history in the face of struggle.

By 1972, a year after Virginia Castro graduated from Metro, Auraria had been cleared out and former residents relocated to parts south and west. This only motivated the movement to work harder.

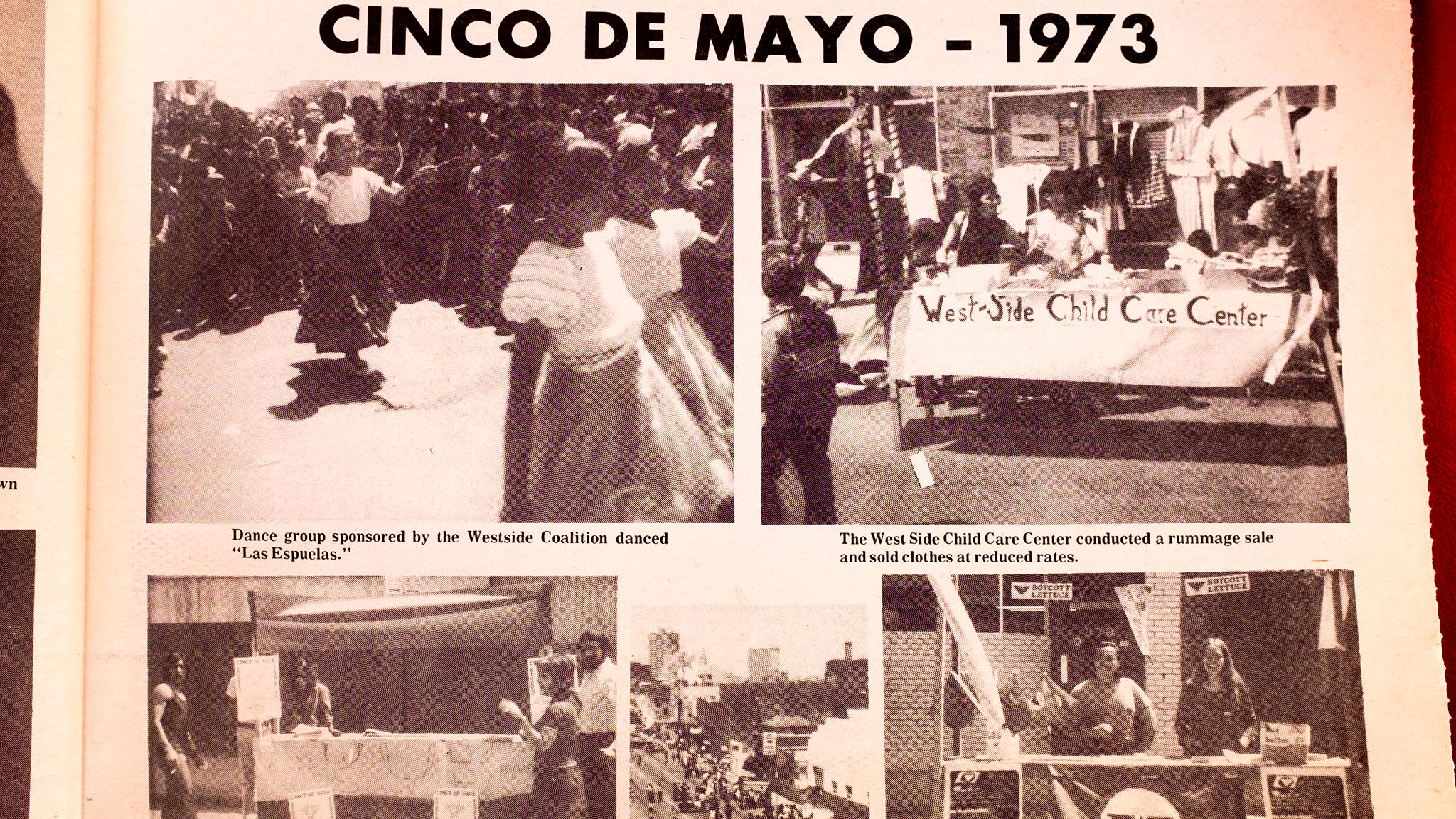

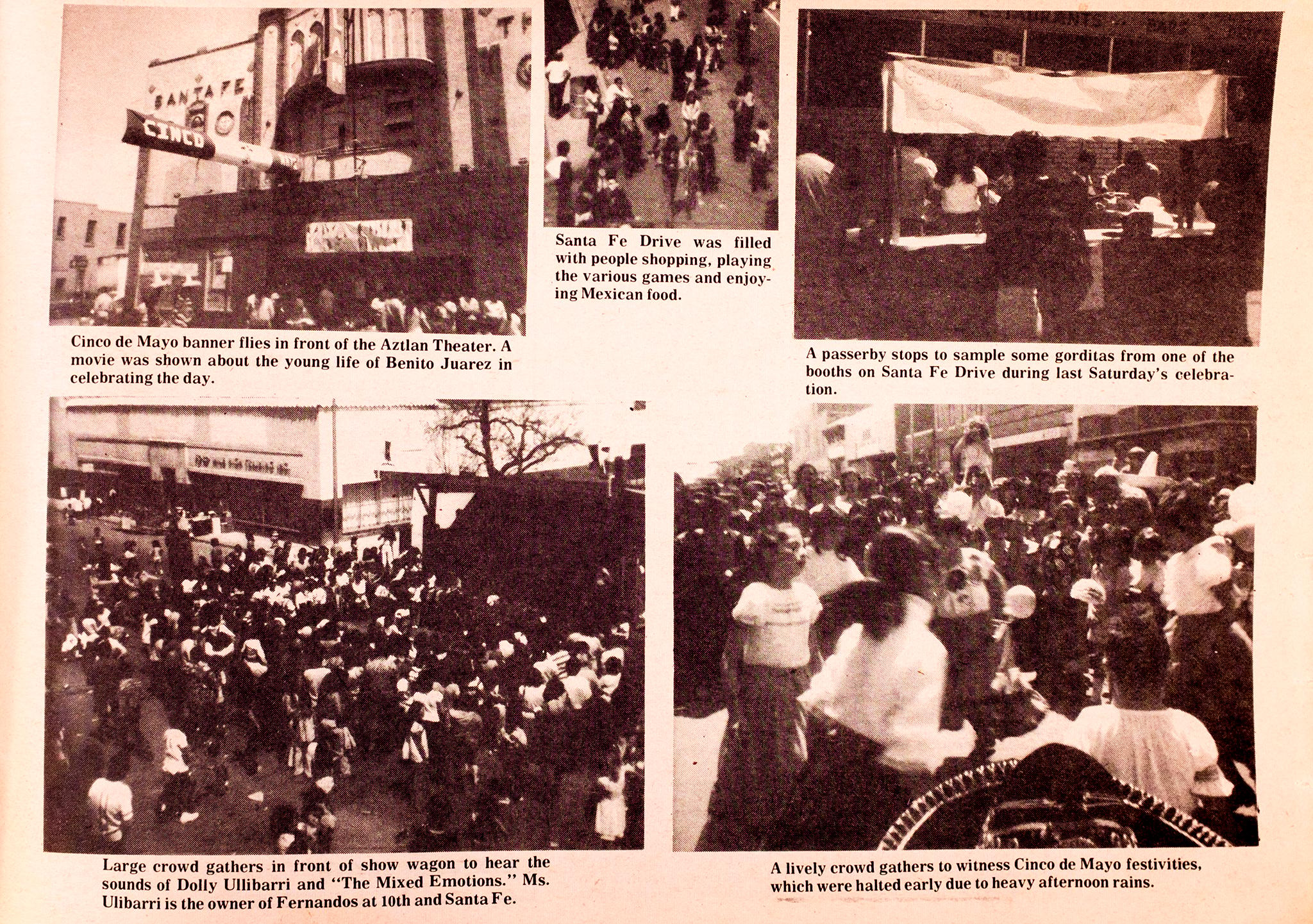

In 1973, the West Side Coalition organized the city’s first Cinco de Mayo festival. They took over Santa Fe Drive and filled it with music, dancing and food. The West Side Recorder, a local newspaper that was deeply intertwined with the Chicano effort, reported that at least 4,000 people attended and dubbed the event a success despite rain that ended the celebration earlier than expected.

“It was wonderful,” Castro recalled.

Cultural expression, Castillo said, was key to their cause.

"Part of the Chicano movement was to rebuild those roots and give people back what they had lost, the cultural part," he said. "Cinco de Mayo becomes a symbol. It’s a symbol of freedom, a symbol of the responsibility that we as free people have."

While people from Mexico don't often celebrate Cinco, it became central to the Chicano cause.

Castillo said they were "informing people that we were here, that we were part of this country, and that we were going to celebrate the way that we celebrate."

As a result, “Denver became a super nationally recognized hub of activism,” he said. “Santa Fe Drive becomes the Mecca, the place you want to be to practice who you are and not be criticized.”

The movement's momentum also allowed Richard, Castro's husband, to enter city and state politics. He worked for Denver Mayor Federico Peña and as a multi-term state representative. In parallel with the West Side Coalition's cultural efforts, he and others were able to advocate for their communities at a higher level.

"It was the beginning of a community," she said. "A viable, economically stable residential community that was on the right track."

Despite their successes, neighborhoods around Santa Fe Drive fell into decline.

Veronica Barela grew up in La Alma-Lincoln park and spent her career running community development projects for the neighborhood. She's still involved in similar efforts today, and recently filed to run for City Council as District 3's representative.

By the late 70s, she said, the strip had become neglected and derelict. It wasn't vacant, "just ugly and boarded up." This motivated a new effort for the neighborhood.

By that time, Castillo said, the Chicano movement had lost steam in the wake of a high-profile bombing against the group and a radicalization of Corky Gonzales' organization, the Crusade for Justice. The Cinco de Mayo celebration tapered off, Castro had shifted her focus to taking care of her kids, and there became space for new community advocates like Barela.

"I saw it in its heyday, and I saw it decline," she said. "I used to daydream that I had a magic wand and it would turn into something different. It was very painful."

She began working for Newsed, a community development corporation that was tasked with reinvigorating the neighborhood. She'd eventually become its executive director. Today, her daughter, Andrea, holds that seat.

Newsed took a new direction to support the community. Instead of political operations, it focused on commercial development. Under Barela's leadership, Newsed began to foster strip malls and shopping centers in the area, "anchor projects" that would attract new businesses and money. Santa Fe Drive became her obsession.

"When we started revitalizing the strip we were very aggressive, we had tunnel vision," she said. Even though she could never manage to widen the sidewalks along the strip, Newsed led an effort to build lighting and benches.

"We had a streetscaping program, we had a facade program, we had architectural guidelines and everything," she said. "It was real tight and structured."

And they, too, turned to cultural expression as a means to foster that commercial growth and lift up the community.

In 1987, Newsed brought Cinco de Mayo back to Santa Fe. It was meant to be a fundraiser to support their development programs, "but it was also a tool to bring attention to the Santa Fe Drive corridor," Andrea said. "And it worked. People just kept moving in, and moving in, and moving in."

That Cinco celebration "took off like a bird," Barela said, and pretty soon it was too big for the neighborhood to contain. Eventually, it moved to Civic Center Park, where it still is held each year.

"It was a great way to celebrate the neighborhood’s roots, its Latino roots, culture," she said, and "again, as a way to say: this is our neighborhood, pay attention to it."

Newsed's commercial stimulus worked, too, and pretty soon Santa Fe Drive began to attract new ventures.

"We had these great programs but not a lot of control of who’s gonna move in," Barela said. "It just started evolving into an arts district."

Art helped revived Santa Fe Drive.

Among the early artistic organizations that moved onto Santa Fe Drive was the Chicano Humanities and Arts Council, better known simply as CHAC.

Stevon Lucero was one of CHAC's founding members, and said he came up with the name. Their group began in 1979 in Denver's north side. They started to throw gallery shows that were, to his surprise, met with great interest from the community.

"We always attracted an audience, and I think it’s because CHAC fulfilled a need in the community," he said. "First of all, we created CHAC because Chicano artists were not seen as being serious."

Just as the Chicano movement a decade earlier sought to carve out space for Latino communities in Denver's political life, CHAC's mission was to make a dent in the city's cultural scene in the face of prejudice. And like their political brethren, CHAC, too, found a home on Santa Fe Drive.

In 1991, after Newsed's economic stimulus had begun to stem change in the neighborhood, CHAC members relocated to a space on Santa Fe near Eighth Avenue.

"CHAC was one of the very first groups that got a space there," Lucero said. "We got a guy who rented to us because he wanted to see something happen, because it was a dying street."

Their move, borne out of the Chicano identity established in the '60s, enabled by the economic development of the '80s, was the start of the street's artistic character that persists today.

"It only takes a few before other artists start recognizing that this is an area that they can be affordably and sell art," Barela said.

Lucero thinks it was a natural progression because arts were deeply intertwined with Chicano culture.

"Look at what the young people do in the streets when they’re poor. They fix the cars up, they turn them into low riders. They paint pictures on them. They tattoo themselves when they’re in prison. They draw, they paint," he said. "There’s this inherent thing within our community, and it’s part of this kind of spirituality that we have."

The movement's connection with their past, roots in Catholic mysticism and indigenous spirituality, created an important role for artistic expression. Like the Cinco de Mayo celebrations, it was a way to affirm their identity and show the city who they were.

"When a community can do things together collectively and share it, it creates a bonding and a sense of collective unity. It builds on itself and it grows. It makes and defines what a people is," Lucero said.

The community's work to lift up Santa Fe Drive inevitably attracted outside interest.

In April, CHAC was priced out of their Santa Fe space and moved further south along the street. It was a sign, to some, that things in the neighborhood had begun to change.

Lucero said he believes the gallery's presence helped create the allure that brought new people and money into the neighborhood. CHAC's presence wasn't the only one.

Barela, who helped foster commercial growth and brought in amenities like the King Soopers nearby, is sure the infrastructure she helped build paved the way for Santa Fe's success. Today, the neighborhood has lost the base community Newsed once served: "La Alma-Lincoln Park’s pretty much getting gentrified."

Castro, who fought to keep the Auraria campus from encroaching across Colfax, also felt the early Chicano movement, "saved the land for" new interests. For her, history might be repeating itself: "How many times can a person go through this in a lifetime?"

Lucero, a soulful optimist, said he sees a "crossroads moment" ahead. It's a time to make choices, even if he can't see where the path might lead. "Whatever it is, it’s not going to be what it was," he said.

CHAC's new home on Santa Fe between Second and Third Avenues exists on an area of the street that never quite saw commercial success the way it did north of Sixth. Just as the gallery helped pioneer the revitalization of the neighborhood's main drag, he said, "Maybe we will be the catalyst that will bring the rest of Santa Fe all the way down."

While the loss of Santa Fe Drive's deeply Chicano character stings for many, Castillo, at least, is satisfied by the movement's permanent improvements for the community.

"For those of us who are old veteranos, the old timers, there’s a sense of loss," Castillo said. But at Metro today, where he heads the Chicano Studies department a stone's throw from Auraria's last-remaining homes, he's in constant contact with the movement's legacy.

"When I see here young kids with masters degrees — young — in public policy and management, getting those meetings, I’m thinking, goddamn! They’re sharp! It’s impressive! It’s impressive to hear these young Chicanos get up there and do what they need to do," he said. "We didn’t have that. All we had was passion — street knowledge about what we knew justice meant to us."