The naming and renaming of things in Denver has been a topic of interest lately, what with all the RiNos and LoHis and other neighborhood branding efforts. It's not the first time.

Back in the early 1900s, the residents of Denver had a similar argument about Santa Fe Drive. It pitted "pioneers" against the city's later arrivals, and it even resulted in a temporary new name for the street.

But let's start with the name "Santa Fe" itself.

From its early days, it was "West Denver's Main Street," as historian Phil Goodstein writes in How the West Side Won, a detailed and fascinating history of the area.

One legend says that it was linked to the Santa Fe Trail, the famous wagon road that ran from St. Louis to New Mexico. Some promoters claimed it was the "oldest road in America," following the supposed path of an ancient trail from Canada to Mexico, according to Goodstein.

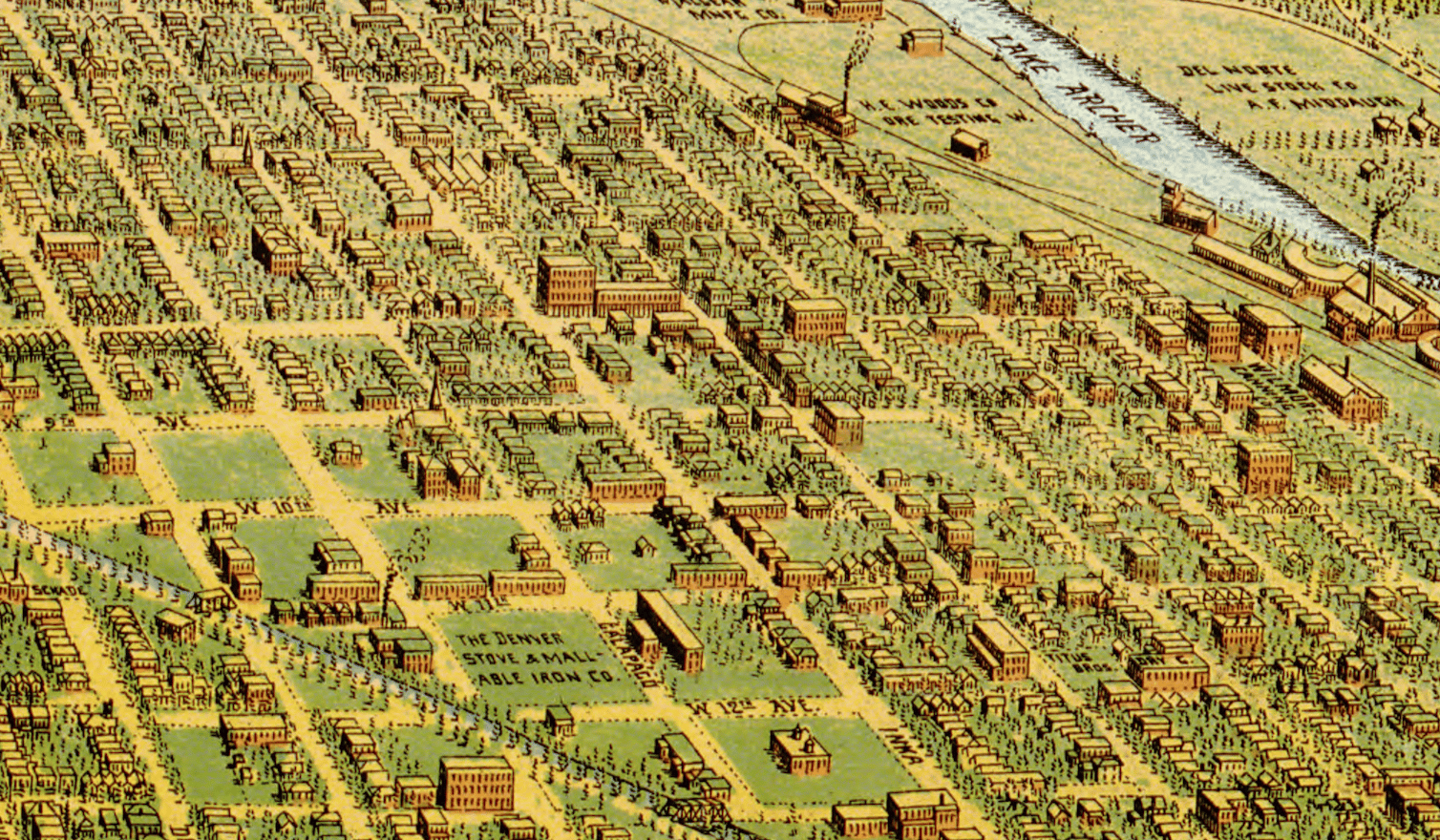

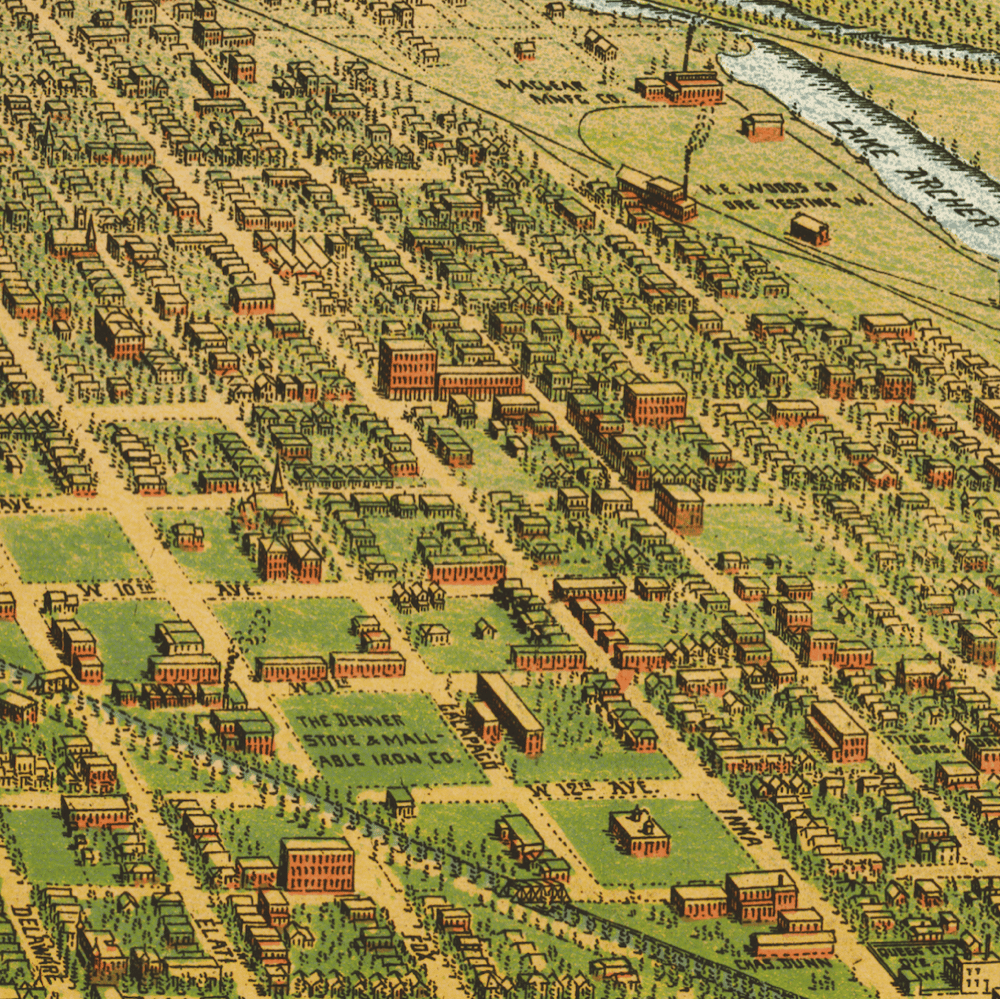

The route had a few other names in pioneer days, but it took the Santa Fe name early in Denver's city history, including on an 1887 map where it appeared as "Santa Fe Avenue."

Somebody's always got to change something.

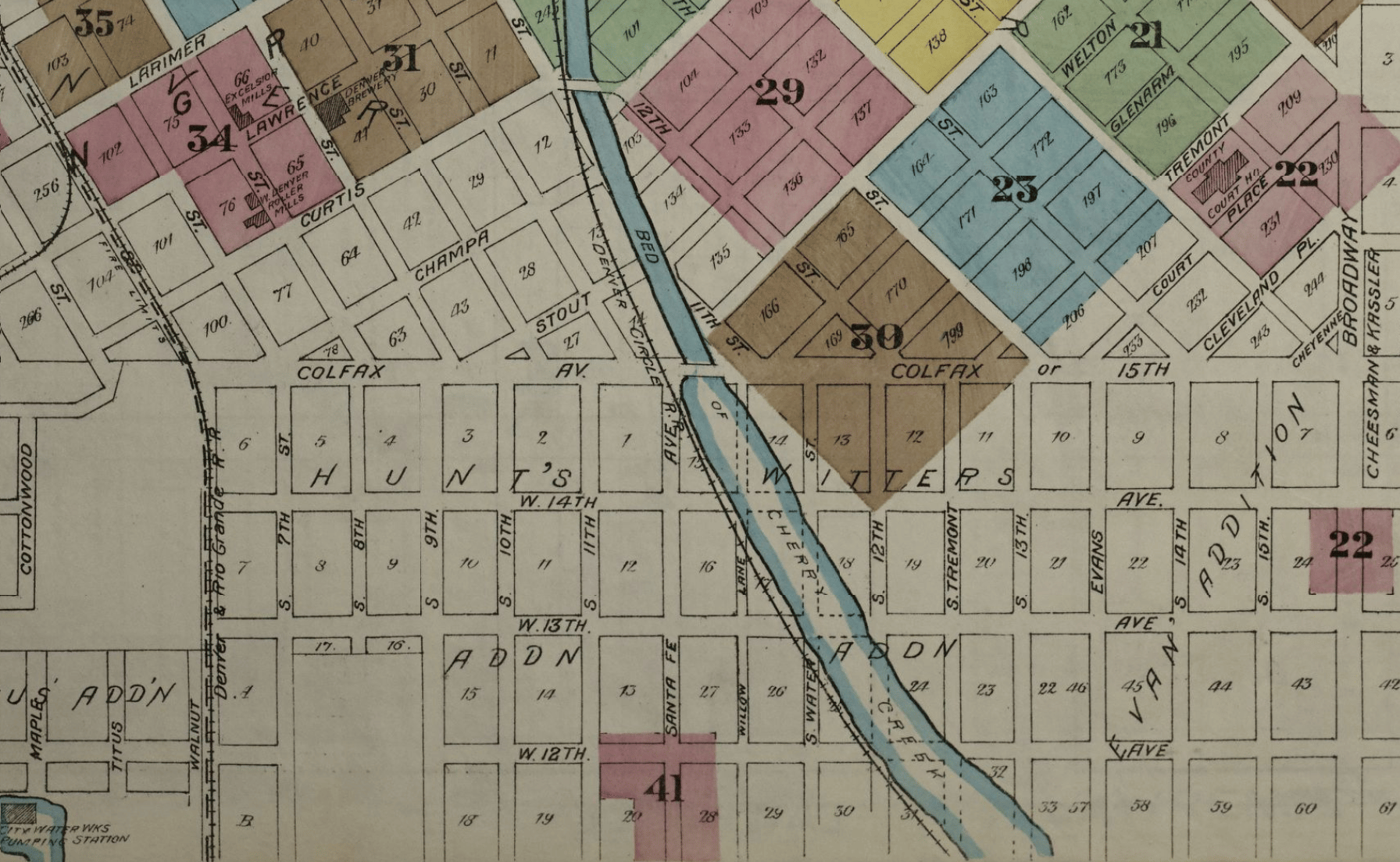

In the early 1900s, city planners decided to rename the streets west of Broadway. At that point, most of the other north-south streets had numbered names, such as South Ninth Street.

Under the new scheme, they took on their current names. It's an alphabetical system, with streets from Acoma to Zuni renamed for Native American tribes.

The new scheme required a "j" name for Santa Fe. The replacement options, according to Goodstein, included Jemez and Jicarilla -- but complaints about "exotic" names shot those options down.

Instead, Santa Fe took the name "Jason Street," an apparent reference to the Argonauts. And it stayed that way for about a decade, until the Denver council changed the name back around 1912.

An article published at the time by Denver Municipal Facts says that the change was the result of a petition of "pioneer citizens." The newspaper repeated the claim that the road was part of the old wagon trail --- and it noted that the city was getting ready to pave it.

This was a hot topic of debate at the time. One notable resident, Simpson T. Sopris, wrote scornfully that the city was engaging in revisionist history by changing the name back to Santa Fe. Arguing against the change, he dismissed the idea that the road had any historical connection to the city of Santa Fe.

"For a road from Santa Fe or anywhere to the south to have followed the alleged 'Santa Fe Drive' it would have had to cross scores of gullies, ravines, arroyos" before "it would have ended in the very sandy bed of the Cherry Creek," reads his article. (Thanks to neighborhood historian Dave Stauffer for surfacing that document. Check out his interesting summary, too.)

My favorite part of Sopris' letter of complaint: He refers derisively to the "pioneer" of the 1880s. (Damn transplants.) By the way, this guy's dad was an original prospector and one of Denver's first mayors. They had a mountain named after them.

Goodstein, however, writes that the road did connect eventually with Santa Fe. And, either way, the new-old name stuck. To the historian, the entire episode was an example of government run amok.

"What happens when city planners don’t consult residents when they insist it on being Jason Street?" Goodstein said in an interview.

Soon after the re-renaming, many of the buildings of the commercial district were cropping up, including the Byers Library, dating to 1918. It's the only registered historic landmark on the strip, but others are older. For example, the Denver Art Society building dates to 1903, according to property records, while part of Museo de las Americas' home went up in 1925.

Along the way, the city would steadily widen the road, much to the chagrin of Goodstein, a longtime resident of the west side. "The city has done all in its power to ruin it over the years, by traffic expansions," he said in an interview. As he details in his book, Santa Fe was first widened in the 1930s, and later converted to a speedy one-way in 1967.

It escaped, however, the fate of total demolition. The Santa Fe corridor stood in the path of the proposed Columbine Freeway, as detailed in Could Be Denver and by Goodstein. That plan, which would have laced new highways through downtown Denver, died in the face of intense opposition.

Today, fittingly, Santa Fe is still part of a north-south route. If you trace it down toward Littleton, you'll find that it merges with U.S. 85 -- itself a part of the CanAm Highway route that links the United States with Canada.

So, one way or another, a trip down Santa Fe will take you somewhere interesting.

Many thanks to Phil Goodstein, who has worked for decades to chronicle Denver's history. Check out his book, which covers Santa Fe and western Denver in much greater detail.