Experts say Denver's air quality is generally much better today than it was 20 years ago, but increasingly we are seeing waves of wildfire smoke wash over the city. You probably noticed if you looked up this week. The haze is apparent, and there's data to back up that observation.

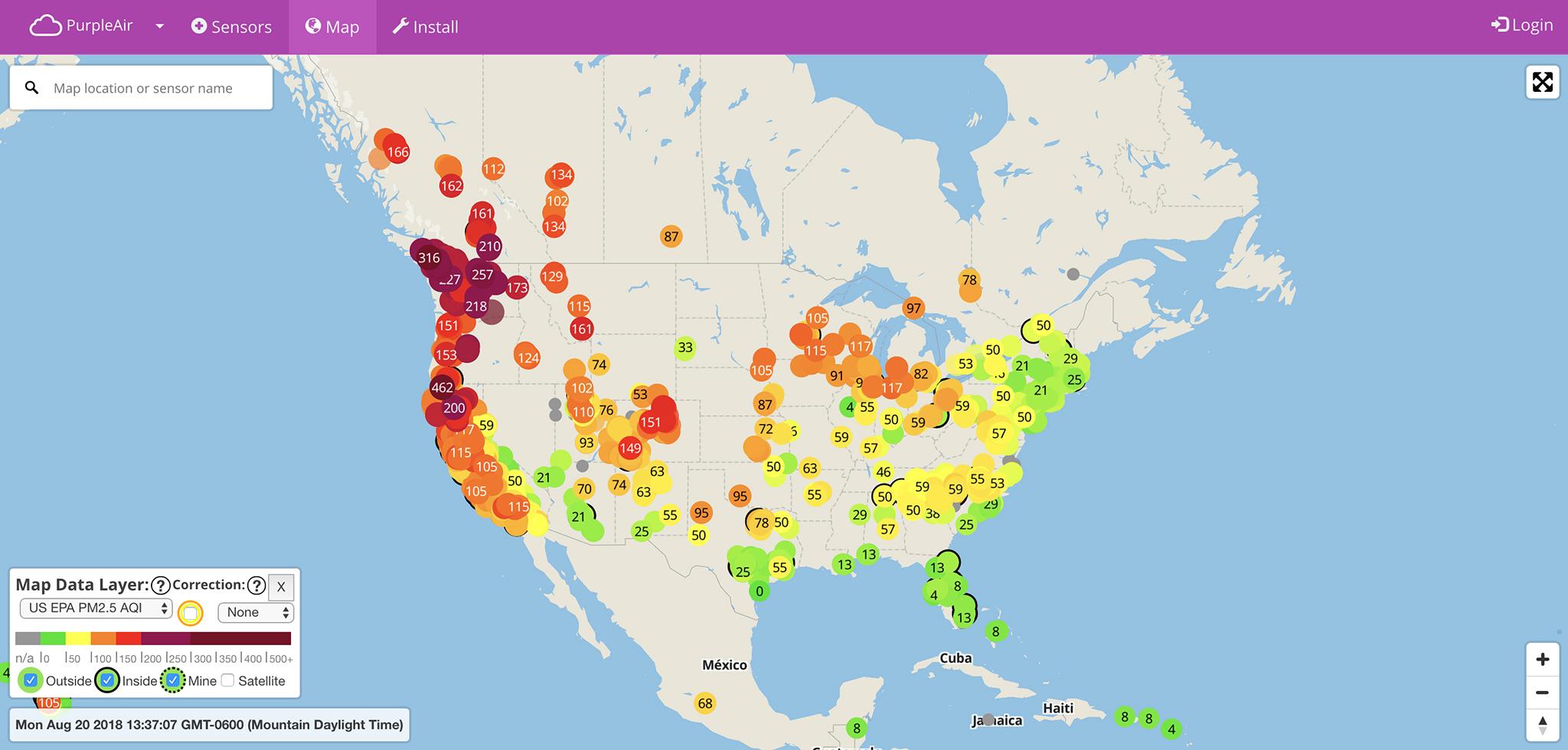

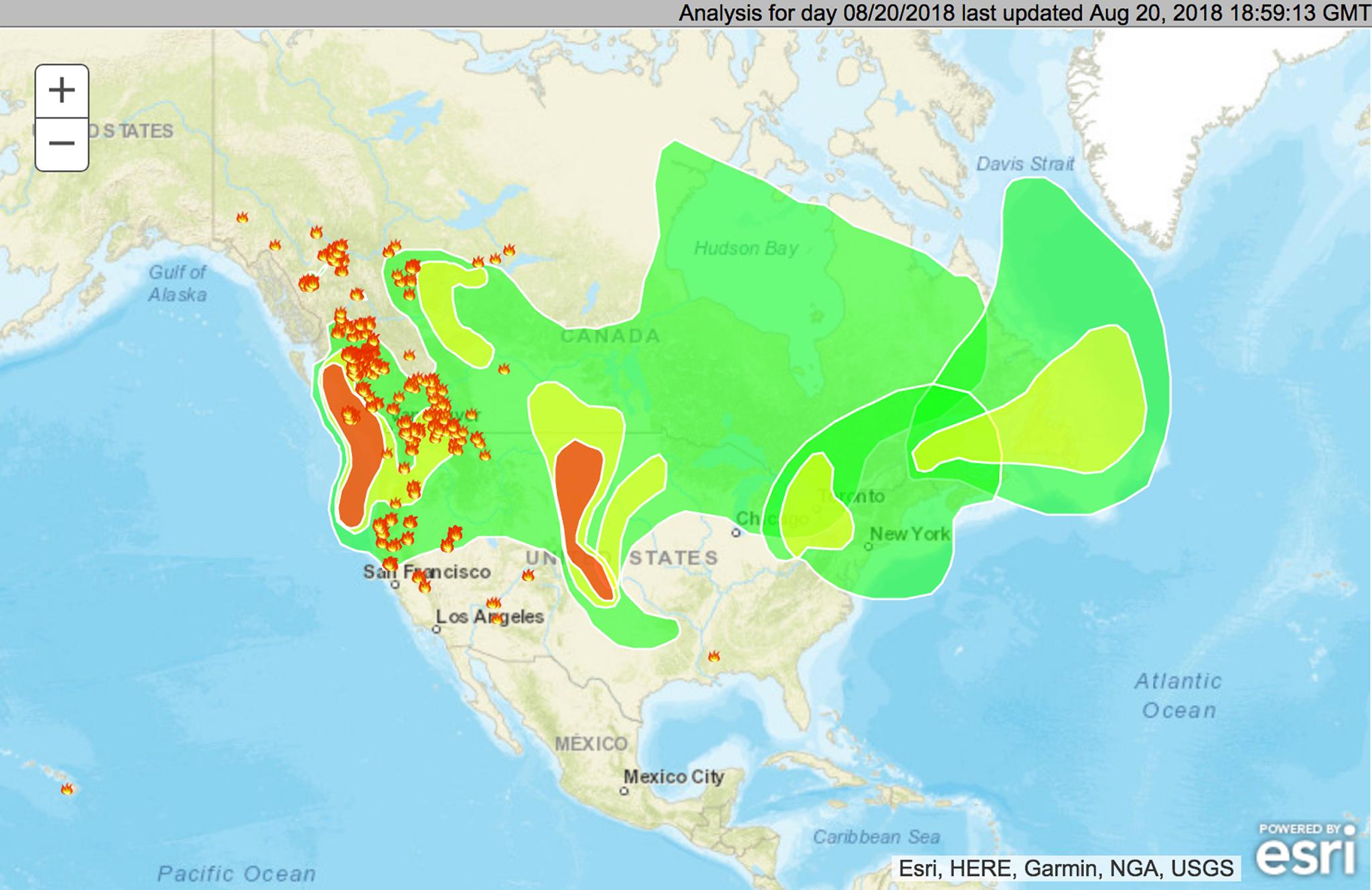

Colorado's state air quality office has issued an advisory for 21 counties for Aug. 20, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's wildfire map shows America's whole central corridor blanketed in outfall from western fires, and PurpleAir, maker of cheap air monitors, also has a map showing sensors across the west detecting poor quality air.

PurpleAir's map, in particular, shows elevated levels around the Denver-metro area.

Gabriele Pfister, a leading air quality expert with the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, told Denverite she's wary of giving too much merit to all of those at-home sensors -- they're not as reliable as the $100,000 machines the EPA uses -- but then again, she's not surprised.

"I can tell you that from my office window I can barely make out the Flatirons," she said over the phone. "Usually I have a very nice view."

The state's advisory specifically warns the very young and old and those with respiratory conditions to stay inside. Pfister said it's unclear if the smoke hanging over the city is low enough to cause a serious health risk, but you should still be wary. If you can smell smoke, she said, it's probably not good for you.

She said part of the fuzziness here is that there are still gaps between what researchers know about pollution levels and what they can say for sure are health impacts. This is especially true since we can measure how much particulate matter is in the air, but we're not so good at identifying what chemicals are contained in that pollution.

Cutting back on our own emissions could have big effects on the air we breathe.

While scientists are generally wary of pinning any one event to a warming climate, Pfister said wildfires have been generally getting worse as areas in the west have gotten hotter and dryer.

"There are plenty of studies out there that not only the frequency but also the intensity of wildfires are increasing," she said. "We barely have a spring anymore."

On top of health risks that could mount with wildfire smoke, she said poor air quality in the city can be compounded by our own pollution. And she should know: last year Pfister was co-lead on a study that showed how cars contribute just as much ozone across the Front Range as oil and gas operations.

If we cut back on our own pollution, Pfister said, "you get way more bang for the buck."

Not only does that decrease the overall pollution in the air, which is especially good for days like today, but it could also impact greenhouse gases contributing to rising annual temperatures that are fostering these fires in the first place.

"It’s all connected," she said. "We can’t lose if we improve our air."