Elisabeth Epps is dedicated to getting poor people out of jail and reforming the criminal justice system, and her efforts seem to not have a pause button — even when she herself is headed to jail Monday.

As I interviewed Epps, she was in New York City at a hospital, visiting her brother who had just had triplets. Mid-interview Epps received a text message about someone being stuck in jail with a $25 bond. She quickly told me she had to take a couple minutes, and during that time she made calls to everyone she knew in Denver to ensure that the young man would not have to sit in jail over such a small amount of money.

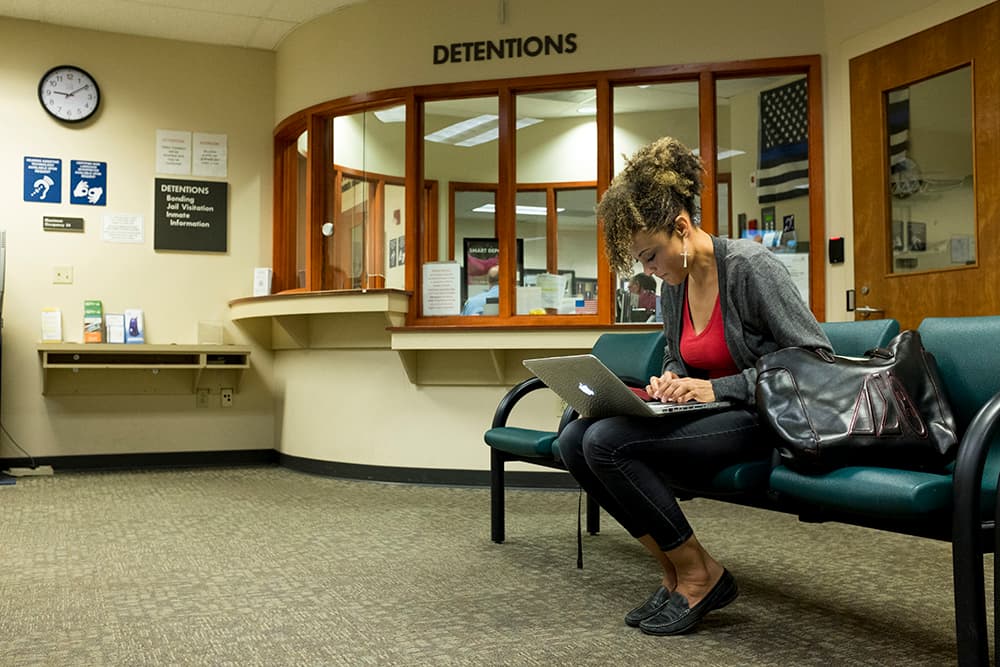

Epps is a well-established criminal justice reform advocate and has in the last several months launched campaigns that have gotten numerous people out of incarceration on small bonds.

To her, not many people deserve to be detained in the prison system, and she has support for that sentiment in community members who have helped her fund many of the bailouts. In fact, just this month Epps has gotten 22 people out of Arapahoe County jail, she said. She is responsible for some large-scale bail raising efforts like this year's Father's Day and Mother's Day bailouts.

On Monday, Epps is slated to turn herself in for a two-year-old obstruction charge.

In 2015, after an encounter with several Aurora Police Department officers, Epps was arrested and eventually charged with trespassing, resisting arrest, and obstructing a peace officer. She was ultimately convicted of obstructing a peace officer, but a jury dropped the trespassing and resisting arrest charges. Judge Shawn Day sentenced her to 90 days with a possible reduction to 60 days based on behavior and Judge Elizabeth A. Weishaupl later confirmed that conviction.

She appealed the final verdict and has continued to fight the case by representing herself and working with two different pro-bono lawyers who were interested in keeping the anti-jail activist free.

Epps has stood in the gap between many community members and a judicial system she believes disproportionately punishes poor people and minorities, especially when those descriptions overlap. Mickey Howard, a young black man who found himself arrested for missing a court date, said Epps' work kept him from potentially sitting in jail for several months with bail set at just $10. He said he found her care for the incarcerated genuinely inspirational.

“I felt like this is like some black revolutionary type shit. She's a real modern day revolutionary," he said. "It's cool to see somebody like that and actually know somebody like that. She's like a Tupac or something."

Her passion and care for others have impacted how Howard envisions his role in the community going forward.

“She actually she cares, she was actually there when I got out jail,” he said. “She got me woke a little bit more about how the world is, and got me feeling like whenever I’m in a better position too, I can give back.”

Hundreds of others have written letters of support asking for her sentence to be reduced, saying they feel that losing Epps from the streets would have negative impacts on the community, especially the disenfranchised members of it.

One of those writers is Rebekah Henderson, the host of the Off-Color Podcast, who has had Epps on her show several times to speak about the criminal justice system and what reform efforts would look like. Henderson said that seeing Epps go to jail is a peak example of the flaws that exist in the criminal justice system.

"Elisabeth has been pushing my thoughts around our criminal justice system since we first met at a Citizens Oversight Board meeting last fall," she said. "Her work of bailing people out of jail to prevent them from possibly dying while in custody is admirable and unfortunately necessary. She is not a danger to the community. She doesn't belong in a cage.”

Epps says she was just trying to help a young man in distress. Police say otherwise.

The 2015 encounter with the officers began with Epps hanging out with some friends during a pool party at an apartment complex when she noticed a young white man, Cody Shelby, having a what she described as a “breakdown," hitting a tree outside the complex until his hands were bleeding.

Epps says she approached Shelby because he looked scared and nonviolent but, based on her observations, clearly needed help and attention. She says she was able to get him to tell her the phone number of someone he knew that would come to pick him up. After they made the call, they sat on the curb waiting for his stepmother to arrive, according to Epps, and that's when police showed up.

Upon arrival, the police claim, Epps repeatedly told Shelby he did not have to speak with the officers if he didn’t feel comfortable. She had gone back up the stairs to retrieve some of her belongings but when she returned she noticed them speaking with Shelby and she then again advised that he didn’t have to talk to the officers. Epps claims that once the officers arrived, Shelby began to become agitated again, and police say Shelby was unresponsive to their questions.

Epps says she communicated that she knew Shelby and had contacted someone who also knew Shelby, but officers say she provided no identifying information for Shelby, nor did she indicate that someone was contacted that knew Shelby.

Shelby and Epps then began to walk around the apartment complex, and the officer on the scene assumed that it was in an attempt to find Shelby’s ride as Epps was walking with a guiding hand on Shelby’s back. When it became clear to officers that the car they were looking for was not in the parking lot, they continued their investigation and Epps continued to remind Shelby he did not have to talk to the officers. Shelby began to climb the fence separating a staircase from the pool area, and while they were able to get Shelby off the fence, all three officers claimed Epps made that process difficult by placing herself in between the officers and Shelby.

It was then that another woman, Shelby’s girlfriend, approached the group and alerted them that Shelby’s mother was in the parking lot and ready to take her son away from the scene. Everyone, including the officers, then moved towards the waiting car, and, according to police, the complex’s security officer determined that Epps was causing a disturbance. He also testified that anytime someone creates an issue according to their best practices they ask the person to leave the property.

According to police, on the way to the vehicle, an officer asked Epps if she lived on the property and Epps said yes. The officers then asked Epps what apartment number she lived at, and she refused to answer, saying she did not have to answer any more of his questions, and walked away. The officer then told her to stop so he could speak with her and then, the officer claims, Epps cursed at him and continued walking.

The officer caught up with Epps and informed her that she needed to leave the property. Shelby left with his mother, and the security officer said Epps needed to leave the premises a second time and asked officers to help.

Then, according to Epps, the security guard allowed her to go back to the pool area and retrieve her belongings. As she did that, officers followed her. Once in the pool area, Epps reiterated that she was not going to answer any questions. The officer was then under the impression that she was no longer gathering her belongings and claims he grabbed her arm and attempted to “escort her out of the pool area.” Epps had a different interpretation of this moment, and according to her, she was grabbed and slammed into a fence.

Once outside, police claim, Epps began to swing her arms and officers used a control hold to stop her. Epps says she was then arrested, but claims she heard no command to stop moving or acknowledgment that she was being detained until after being placed in handcuffs.

Epps went limp, and officers then had to carry her to the police car where officers claim she was being unruly and doing things like laying sideways in the seat and repeatedly unfastening her seatbelt. She also sat with her legs outside of the patrol car making it impossible for officers to close the door and because of this they used a hobble to restrain her, called an ambulance and had her taken away in a gurney.

Epps' activism has given her reason to worry, but her experience has given her more motivation.

Epps does have some concerns about her time in prison, mainly due to her complicated relationship with police that has only been compounded by PTSD that she says dates to a law enforcement related event when she was 14 years old. But dealing with the jailing process from a first-person perspective has been eye-opening and made her feel more dedicated to her cause than ever before.

“To say I feel more inspired is an understatement," Epps said. "I hadn’t done jail time before going to law school but now, seeing it upfront, the appeals process is so dehumanizing.”

Her latest appeal was denied by a judge, who said she didn't have to actually succeed in hindering police enforcement, as long as officers believed she intended to do so. The judge cited her refusal to leave the premises, answer questions or step away for the officers' investigation of Shelby, as well as her difficult behavior in the police car.

The judge concluded that it is the intention that matters more than whether or not the defendant committed the crime they’ve been convicted of: “A court need not determine whether the defendant actually conducted the crime for which the defendant was arrested but only that the arresting officers made a good faith determination that the defendant had committed a crime.”

The Aurora Police Department noted that this is not a very common charge, but it is used if the circumstances meet the criteria for obstruction.

“The way the process works is we are called and then we can take police action, and if a crime has occurred we can issue a summons or an arrest,” said Ken Forrest, a public information officer for the Aurora Police Department.

Epps is disappointed by the prospect of a substantial jail sentence being served by someone who is nonviolent.

“I've maybe met two people in my life as a public defender that needed a timeout in jail. I'm not a violent threat. I was convicted in 2015,” Epps said.

She also is concerned that her history as a criminal justice reformer led to an increased level of scrutiny from the courts and police officers in the Aurora criminal justice system. She feels as though she should have kept fighting the courts to keep her out of jail, but her last pro bono lawyer couldn’t continue to fight the case and she is quickly running out of resources to fight this legal battle.

"I feel guilty about quitting and giving up and going to jail," she said. "People fought to the end but I feel like I’m a quitter. I almost feel guilty for using my community to help me because I feel like there's a lot of people rotting in that cage that don’t have anybody.”

Before she reports, she is trying to find someone to take over her work bailing people out of jail, and once she serves her sentence, she plans on doubling down on her mission and continuing to advocate for criminal justice reform with more intensity.

Correction: This article originally misidentified the original sentencing judge. It has been updated.