On Tuesday, members of the advocacy group Denver Homeless Out Loud rallied in front of Denver Downtown Partnership headquarters off the 16th Street Mall. The occasion was the release of a new study by the Policy Advisory Clinic at the University of California Berkeley law school, a scathing report on business improvement districts -- a common kind of semi-governmental organization like DDP and many others in the city. The study referred to them, in its title, as "Homeless Exclusion Districts."

In its executive summary, the report says that BIDs work with cities to exclude unhoused people from public spaces through policy, police enforcement and direction toward social service programs. Some local districts say they’ve been hard at work to deliver help to unhoused people in their neighborhoods -- and that not all BIDs should be painted with the same brush.

DHOL is a member of the Western Regional Advocacy Project, a rights group for people experiencing homeless that helped survey 186 BIDs and people living on the street in a number of cities in California.

The report focuses on California exclusively.

While the rally centered on the DDP and the Downtown Denver Business Improvement District, which DDP operates, Denver Homeless Out Loud's Terese Howard said the problems outlined by the study are true of BIDs across Denver and the nation.

During the rally, advocates pointed toward DDP's advocacy of Denver's "urban camping ban" as proof that Denver is no different from California.

The ban, which makes it illegal for a person to cover themselves while sleeping in public, was passed in 2012. It's become increasingly controversial, and now candidates for city offices are using its repeal as a platform issue. DHOL protested the ordinance in 2016 and took urban camping tickets to court, though they failed to successfully fight the charges.

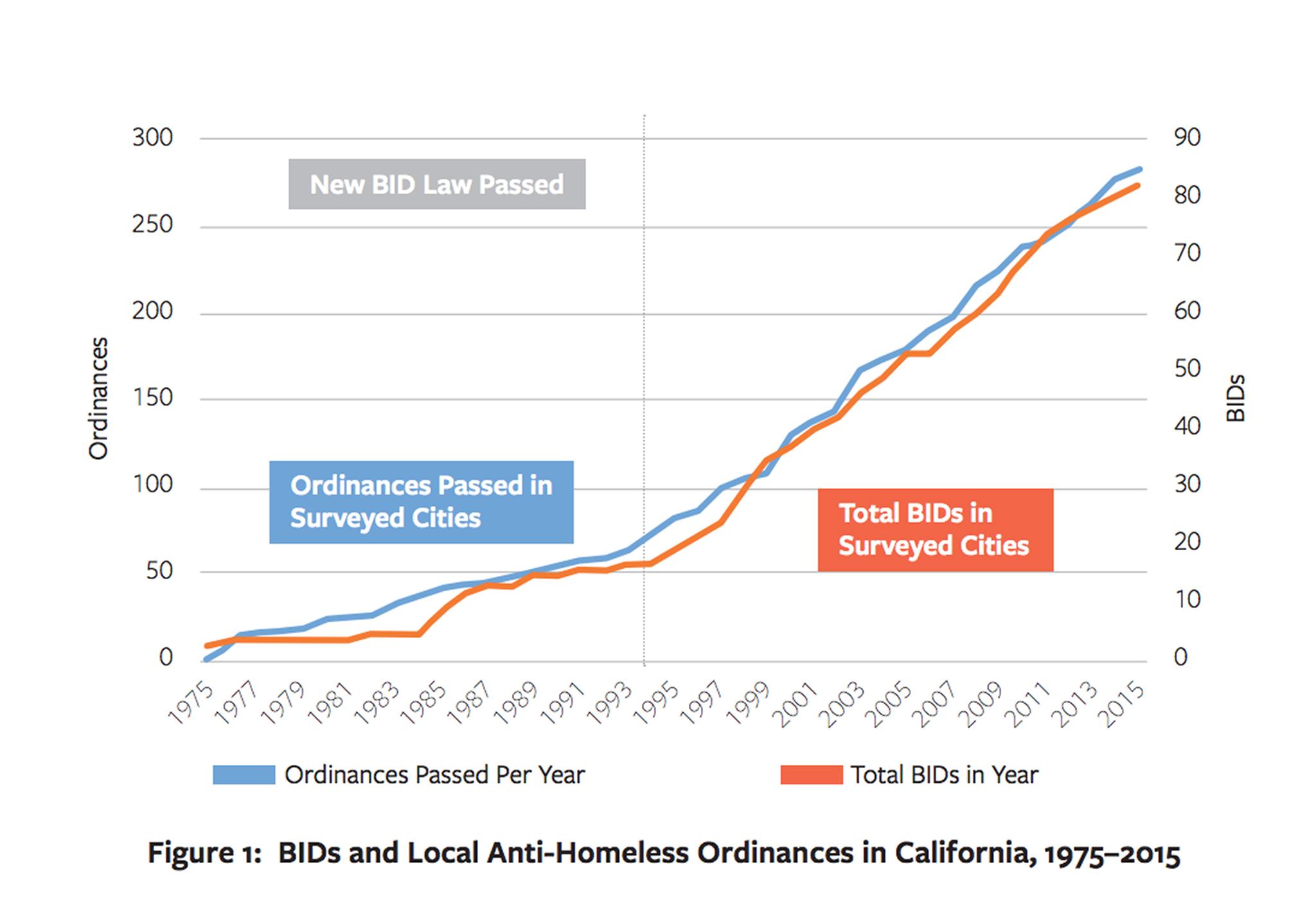

Berkeley Law's report says "the proliferation of anti-homeless laws correlates strongly with the increase in the number and authority of BIDs" in California. It cites similar measures taken by California cities that allow police to confiscate property or force people resting in public areas to move along.

The Downtown Denver Partnership declined to comment for this story, but their 2011-2012 annual report reads: "The Partnership helped lead the successful lobbying efforts to institute a city-wide unauthorized camping ban to address behaviors negatively affecting businesses and the Downtown environment."

DHOL's rally came at a time when they're preparing to deliver petitions to get a "right-to-rest" measure on the May 2019 Denver ballot, which they hope will end the ban. A version of the measure failed to pass muster in the state legislature four times, and advocates say taking it to the people at the local level might give it a better shot at success.

Howard said BID advocacy for anti-homeless policy is an improper use of public funds for discriminatory action.

She said partnerships like DDP are spending money to "privatize spaces and drive out homeless people, violate people's rights and cater to tourists and shoppers."

In Denver, business improvement districts are funded through fees imposed on member businesses that are calculated on commercial property space and where the business is located, so their expenses are not being paid for by all Denverites.

The Berkeley Law report says that just under half of the BIDs they surveyed "cited policy advocacy as one of their main expenditures."

It also says that more than two thirds of California BIDs employ paid or volunteer security forces, and that 80 percent "identified 'panhandling and loitering' as 'one of the most important issues that the BID has faced in terms of safety and security.'"

In 2016, DDP shelled out thousands of dollars to fund a new private security force on the 16th Street Mall after some high-profile incidents that took place there. Last year, they said the program resulted in fewer crimes along the strip.

But Howard said the measures are still criminalizing homelessness in the name of safety: "You don’t need to have a law against sitting on the sidewalk to stop someone from thrashing a pipe around."

And her organization's complaints go beyond policy.

Benjamin Dunning, who co-founded DHOL with Howard, led a tour after the rally to visit areas that he said have been designed to keep unhoused people from accessing places that would have otherwise been public. His first stop was Skyline Park, home of a summertime beer garden, that he said was once a nice, shaded space for everyone.

"They don’t want you here unless you’re spending money buying beer."

Frank Locantore, who heads up the Colfax Business Improvement District, said it's not fair to lump every BID into a bad characterization.

"To say all BIDs are uncaring and not doing their part," he said, "is coming from a place of not knowing what the BIDs are doing."

He specifically pointed to Colfax Works, a sister program to Denver Day Works, that aims to provide jobs to people experiencing homelessness. The Colfax BID spent $40,000 to pilot the program this year. They plan to expand the program in coming years and have begun advocating for similar programs in other business districts.

A Colfax Works employee recently praised the program in a Denverite interview, saying it allowed him to get housing after ending up homeless in Denver last winter. Locantore said local business interests and residents have also been supportive, but he recognizes the program is not necessarily solving the underlying problem.

"At the macro level, we just desperately need more housing," he said.

But they can't provide housing. The BID isn't a developer or a public housing authority. Instead, they asked themselves: "Can we provide employment?"

Even so, he admitted that there is a tough line to walk when it comes to being inclusive. While their mantra is "Colfax is a place where everyone is welcome," that kind of talk can upset businesses and homeowners nearby.

It's impossible to please everyone, but Locantore said they're doing what they can to foster business in a way that doesn't exclude people, although some of their advocacy has focused on streetscaping to keep people from hanging out along certain areas on Colfax.

"All I’m saying is that a BID is not equal to a sweep," he said.

Gayle Jetchick, executive director of the Havana Business Improvement District, told Denverite her organization has worked with Aurora police to create agreements with business owners that allows officers to remove people who are trespassing after hours. The Colfax BID has created similar agreements in Capitol Hill.

Jetchick said getting her businesses on the same page was a great way to start getting people to services. She and business owners have gotten to know people who are living without shelter in their neighborhood, and there are a number of cases she cited where people living on the street were able to get into housing because of those relationships.

"We've really been able to help a lot of people," she said.

But Dean Saitta, an anthropology professor and program director of the University of Denver's urban studies program, said he doesn't share the opinion that simply directing unhoused people to services is an overall positive: "It’s a red flag that we need to do something alternative, other than militarizing the urban landscape."

And he said he's not surprised by the Berkeley Law report: "Homelessness generally is not good for business."

But it is a side effect of our market economy. As downtown Denver becomes "increasingly white and increasingly wealthy," more and more people "are being left by the wayside, homeless or not."

He said Denverites and city stakeholders across the nation need to realize that our thirst for development and place-making is creating winners and losers.

"We need to wake up to the fact that this is all of our problem."

Corretion: This story erroneously named Gayle Jetchick, executive director of the Havana Business Improvement District, as Pamela Richard.