Pillows, sheets of cardboard and tattered car sun shades line the windows to give JC Reed privacy and a measure of warmth in his home.

Car shades because the 79-year-old lives in a dark blue 1998 Volvo station wagon. He parks next to a supermarket around the corner from the Mayfair duplex he’d called home for a decade. He had to leave three years ago when his landlord died and the four-unit complex was sold to an investor who renovated it beyond what Reed could pay. Reed’s main income source is $760 a month in social security benefits.

“That’s how homelessness came to be for me,” Reed said. “I’m just stuck. Like a lot of people.”

Reed owned The Book Nook at 3220 East Colfax in the 1990s and later moved his used, rare and collectible book business to Ivy and Colfax. He has lived in Denver almost his whole life. His experience of homelessness is shared by other older Denver residents.

This story was prompted by an email from a Denverite reader who described herself as a disabled senior who had just received an eviction notice. "I am desperate to find decent, affordable" housing, the reader wrote.

Shelters are an option, but those who run them say they aren't the best for older people who may have difficulty managing stairs, health problems that could be exacerbated in loud, crowded conditions or equipment like walkers and oxygen tanks that create storage and safety problems.

Denver's seeing more older seniors with similar stories.

Josh Geppelt, vice president for programs at the Denver Rescue Mission, said over the last two years or so the mission’s downtown Lawrence Street Shelter has seen “a sort of consistent surge in not just seniors but specifically older seniors that are all on pretty fixed incomes.”

Geppelt said they report experiences similar to Reed’s of finding their longtime homes no longer affordable because of a change in ownership or because a veteran landlord sees an opportunity to raise the rent in a market where average rents hover around $1,500 a month.

Older homeless people are “the victims of the changing housing environment,” Geppelt said. “Folks are just getting priced out.”

Tammie Andersen, who manages housing in the Denver metro area for Volunteers of America, said, “It’s a bad situation.”

Units fill up quickly when VOA opened Meadows at Montbello, its newest complex for low-income elderly residents in July. “Many, many of those residents were homeless,” Andersen said.

She added that the wait lists at Meadows and at VOA’s seven other Denver area affordable housing communities for seniors were now closed. She believed the same was true for similar properties managed by others. When the wait list recently — and briefly — opened up at one VOA property, 100 people applied within a week, she said. VOA wait lists close when managers estimate those already on them might not get a unit for a year or more.

Nanae Ito has seen the rush when an affordable housing complex for seniors does open its wait list. Ito directs case management for Senior Support Services, Denver's only day center for older people who are homeless or are on the verge of homelessness. Ito and her staff tell clients they could be on a wait list for housing for years, so should look for relatives or friends who could take them in.

"It is a really hard discussion that we have to have daily with many folks here," Ito said.

Her boss, Senior Support Services Executive Director Ted Pascoe, said he knows of many seniors who, like Reed, live in their cars. Others take in roommates to share the rent, even though that might violate their leases and lead to eviction if they are discovered. Pascoe described an elderly man who has for the past year been sleeping on the kitchen floor of a small duplex he shares with three roommates.

Pascoe has seen "a number of our clients get evicted so the landlords could renovate and jack up rents," he said. Even boarding houses and cheap motels are raising room rates in response to growing demand, he said.

Last year 2,400 men and women over 55 received support at Pascoe's Uptown center -- advice from a case manager, a hot meal, a change of underwear, an hour or so on a computer, a place to store belongings too heavy to bring along as they wander the streets. Pascoe has seen a 20 percent jump in clients in the last five years, but thinks that reflects only part of the increase. He believes many never come in to be counted because they find his center so crowded they seek respite instead at libraries or other sites.

Reed said he once spent two hours waiting to see a case worker at the center before giving up and never returning.

Senior Support Services, founded in 1976 by six downtown Denver churches, had been considering enlarging its day center. In the last year and a half, Pascoe said, that evolved into a plan to build its own affordable housing complex that would include a bigger day center and a clinic. He's still looking for land for the project.

Searching for help can be confusing.

Reed said he has been on several affordable housing wait lists and keeps being told his registration records have been lost. He accuses city officials of refusing to help him. Ito, at Senior Support Services, said the array of support services can be difficult to navigate, particularly for people who have not had to look for a home for decades. The elderly Denverite reader who wrote of facing eviction had asked how she could contact LIVE Denver, a pilot program the city launched this year to help low-income home-seekers, but not specifically seniors.

One city program aimed at keeping elderly or disabled Denverites in their homes in the first place provides a partial refund of property taxes, or the equivalent in rent, to low-income Denverites who are 65 years or older or totally disabled. Applications are processed on a first-come basis and it can take months to get a payment. Through its Office of Economic Development the city also has helped finance two dozen affordable housing complexes for a total of more than 1,500 units for seniors and other vulnerable groups such as the disabled. VOA's new Montbello project is among those that have received city support.

Reed has a post office box and a smart phone he uses for email and to research housing options. He muses about cheap rents in rural Kansas he’s read about online.

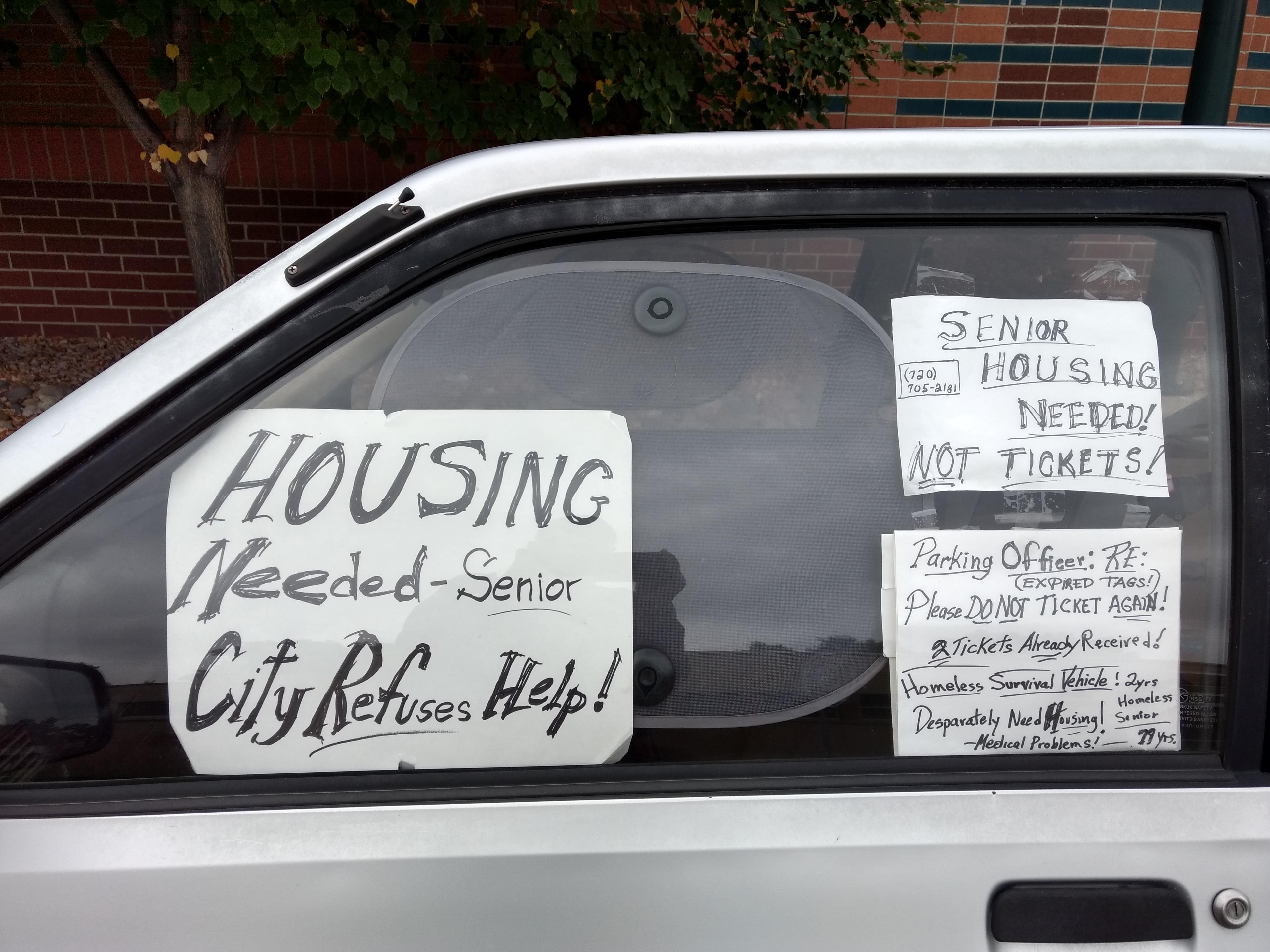

After the engine failed in his 1990 Ford Festiva, Reed scraped together $1,000 to buy the Volvo thinking he would drive to Kansas. He found he’d made a bad deal and the station wagon wasn’t safe for the highway. Now the faded grey Ford, signs in the windows pleading that he not be ticketed, sits behind the Volvo.

He’d like a house or an apartment with room for books he now keeps in a storage locker that costs him $171 a month. If he gets a place, he said, he can supplement his social security by selling books online.

Shelters are not for him, Reed said. He’s a lifelong bachelor who has no children and is estranged from his two sisters. He craves solitude and is sensitive to noise.

Geppelt of the Denver Rescue Mission said shelters should not be a long-term solution for the elderly. One issue is that shelters are usually only open during the evenings. Residents often walk to community centers, libraries or parks during the day.

“You add cold weather and slippery sidewalks and it compounds very quickly for the aging population,” Geppelt said.

He added that shelters don’t have the level of staffing necessary to help residents in and out of bed or up and down stairs. Lawrence Street’s 200 beds are in dormitories up a steep flight of stairs in an older building with no elevator. Elderly residents who can’t manage the stairs end up on the ground floor on one of the 115 mats usually kept for overflow. The shelter has a clinic, but is not equipped to deal with the increase Geppelt has seen in strokes and heart and upper respiratory ailments.

The plight of the elder might be overlooked.

Policy wonks say any household spending more than 30 percent of its income on rent or a mortgage is housing-cost burdened. In Denver's strong economy, seniors on social security are hyper-burdened. As are, increasingly, recent college graduates carrying students loans, working class families and even teachers and first responders.

Pascoe, of the senior day shelter, said, "There's an incredible shortage of all kinds of affordable housing.

"Millennials are competing for housing that our clients theoretically would be competing for if there were just more housing for everybody."

It's a situation in which the elderly might be overlooked.

"It depends on where you're looking,' said Chris Conner, recently named director of Denver's Road Home, the city agency that coordinates services for people experiencing homelessness,

Conner had worked with young people living on the streets before he first came to Denver's Road Home as a staff member seven years ago. When he arrived at the city agency, he pushed for more shelter options for women, who he knew had been underserved. He thought the new shelter beds would be used by the young women he had worked with at Urban Peak. To his surprise many were used by elderly women, and that has continued to be the case.

"We've seen a lot of seniors within the last five years or so kind of descending on safety net services," Conner said.

Reed, huddled in his Volvo as another homeless winter approaches, may seem isolated. He's part of a crowd in crisis.

He powers his cell phone with a car charger, though he knows it’s bad for the car battery to run it while parked. He occasionally drives around the block to get gas. He’s afraid he might lose his parking spot if he’s away too long. It’s the one place he’s found where he said police do not urge him to move along. He walks to the post office once a week to check his box and darts into the grocery store from time to time to buy food and newspapers and use the bathroom. He said the store’s guards are unfriendly, but change often.

“I just sleep in my clothes,” he said on a chilly day. He sat in his car, his skinny frame in a puffy jacket and pants that were stiff and colorless with grime.

“I just use paper towels to clean myself a little bit. There really isn’t any way to keep clean.”

Reed said he’s been displaced more than once in Denver’s burgeoning economy. First the rent went up on two successive Colfax storefronts where he had his book business.

“The same thing kept happening to apartments,” he said. “They start selling them out from under me. They want young tenants with money. I don’t have money.”

“There’s a lot of people in my same boat,” he said. “They’re just invisible people.”