Most elected officials didn't exactly swoon when The Scooters dropped, but on Thursday they cheered Chariot, the latest urban transport company claiming to fill gaps in Denver's bus network. The company, owned by Ford, launches Friday.

"I want it to be here forever," said City Councilwoman Mary Beth Susman, who worked to bring the company here, during a demo Thursday. (For the record, Susman was a pol who swooned.)

Chariot is like a bus but also like a Lyft but also it's a van. It works like this: Riders reserve a seat on the 14-passenger car through an app (like Lyft), but it will only pick-up and drop-off at predetermined stops (like a bus). Passengers ride free for six months because the city bought up service for $250,000.

This thing's only available Friday, Saturday and Sunday from 7 a.m. to 10 p.m. Riders can expect to wait about 12 minutes after requesting a ride.

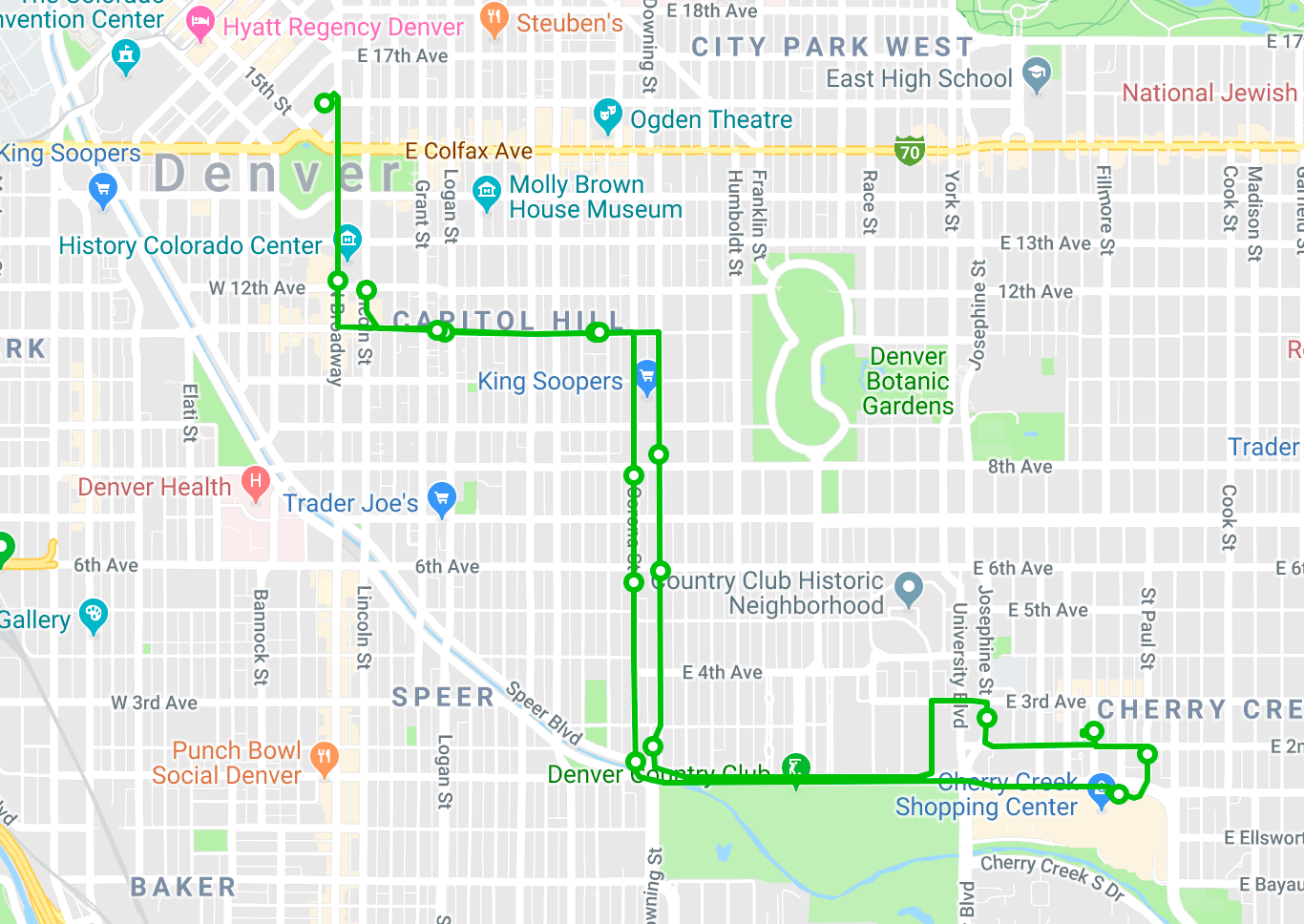

The city government bills the service, branded "City Shuttle," as a coveted solution to "first-last-mile" gaps. (Those are the spaces between the bus/train stop and your origin or destination). The shuttles will pad RTD bus service when it's not available, officials said. Chariot will serve residents, but also has the potential to ferry about 12,000 retail, hotel and service workers who make an average of $30,000 per year, according to a survey by Transportation Solutions.

Between the hotels, homes, restaurants and shops, Cherry Creek has a high density of jobs, making the area ideal for the Chariot pilot, according to Stuart Anderson, executive director of Transportation Solutions. The nonprofit surveyed workers and found that most of them live in Glendale and Capitol Hill.

"They're not long-distance commuters, but almost everybody we surveyed drove alone from those two locations," Anderson said. "We have to teach people how to use microtransit. It's new."

The idea is to give workers new options -- for free at first, and then charge $2.50 per ride after six months if it proves successful. Anderson is working to have employers make Chariot fees a benefit for workers.

The question is whether Chariot will complement or compete with public transit.

Chariot claims to be more than connections to transit. The vans read, "mass transit reinvented." It's fair to say that a few vans with 14 seats each does not equate to mass transit. For comparison, RTD has 1,035 buses with a lot more seats.

The city government's Climate Action Plan aims to double the percentage of transit trips and significantly cut pollution by 2030. It remains to be seen whether a private company adding shuttle vans to the roads can help or hurt.

"That's one of the things we hope to find out," Hancock said. "This is why we do the pilot program, so we can see how the market responds to this and how well Chariot traverses our city and really connects with the riders in our city."

Kate Williams, an elected RTD director and executive director of the Denver Regional Mobility and Access Council, likes the Chariot thing. In theory.

"It's not sustainable, in my opinion," Williams said. "I haven't seen the finance numbers, but if the city wants to give them a quarter of a million dollars every six months, then hey. People who might not ride a scooter might ride a Chariot. I'm about getting cars off of the road and getting people to the backbone -- that's what RTD is and that's what RTD is always gonna be."

Anderson believes the smaller, nimbler vehicles are a better bang for the buck because they'll only operate when riders need them, as opposed to RTD buses that cost money to operate, even when buses are empty. The thing is, RTD serves the same areas Chariot will go. Just not as conveniently and frequently, Anderson said.

Even if local transit advocates like the idea, "microtransit" is not yet proven, hence the pilot.

Chariot only served about nine riders per vehicle per day in New York, according to a report that analyzed the public data.

And transit expert Jarrett Walker, who consulted on Denver's transit plan, argues on his Human Transit blog that app-based services like Chariot don't have the physical capacity to make transit thrive — that moving more people on a bus is more efficient than moving fewer people in a van.

Denver is not New York. It's less dense, and our transit system isn't as robust, hence Chariot's presence.

"In a market like New York... employees already have convenient access to transit," Chariot CEO Grossman said. "But what we found is that the development in New York is moving further, kind of, away from transit. So the residential play in New York is to take residents to transit, to the subway, to the train station.

"We typically work in conjunction with existing public transit. We're not necessarily competing with transit."

We'll find out soon enough. Chariot will have to make ridership data publicly available, according to the agreement between the city and the company.