Data released last week from the FBI shows that bias-motivated crimes in Colorado stayed almost constant in 2017 from the previous years, with 108 crimes in 2017, 109 in 2016 and 107 in 2015. But in Denver, the incidents recorded by the bureau dipped slightly for the third year in a row. The FBI tallied 17 incidents in the city in 2017, 19 in 2016 and 20 in 2015.

The number of bias-motivated crimes -- the official term that includes crimes based on race, religion and sexuality -- the FBI reported in Denver is relatively low. Denver ranked 38th among major U.S. cities last year. But Denver Police data shows that many more incidents not considered crimes were reported throughout the year.

DPD's domestic violence unit currently has three detectives who are trained to identify and log these. In 2017, they logged 61 of those incidents, up from 31 in 2016 and 26 in 2015. This could be the result of better reporting, rather than more occurrences.

Incidents that might not rise to the level of a crime include things like swastikas drawn on pieces of paper and slipped under Regis University doors a few weeks ago, for instance, did not result in any destruction of property and may not be tallied by the FBI. That case in particular is still under investigation, but it demonstrates how the city's numbers could differ from the FBI's.

The most incidents recorded by DPD in 2017, 17 in total, were committed against African Americans. Reports of anti-homosexual and anti-Semitic incidents were next -- 10 were reported for each group.

Lt. Adam Hernandez, who oversees the bias crime detectives, said he personally isn't seeing any trends. Reporters have been asking if there has been an uptick since the 2016 election, but his feeling is that things in the city have been pretty consistent over the years.

"From my perspective, I'm not seeing anything that's dramatically different," he said. "I don't see that we're a very hateful population."

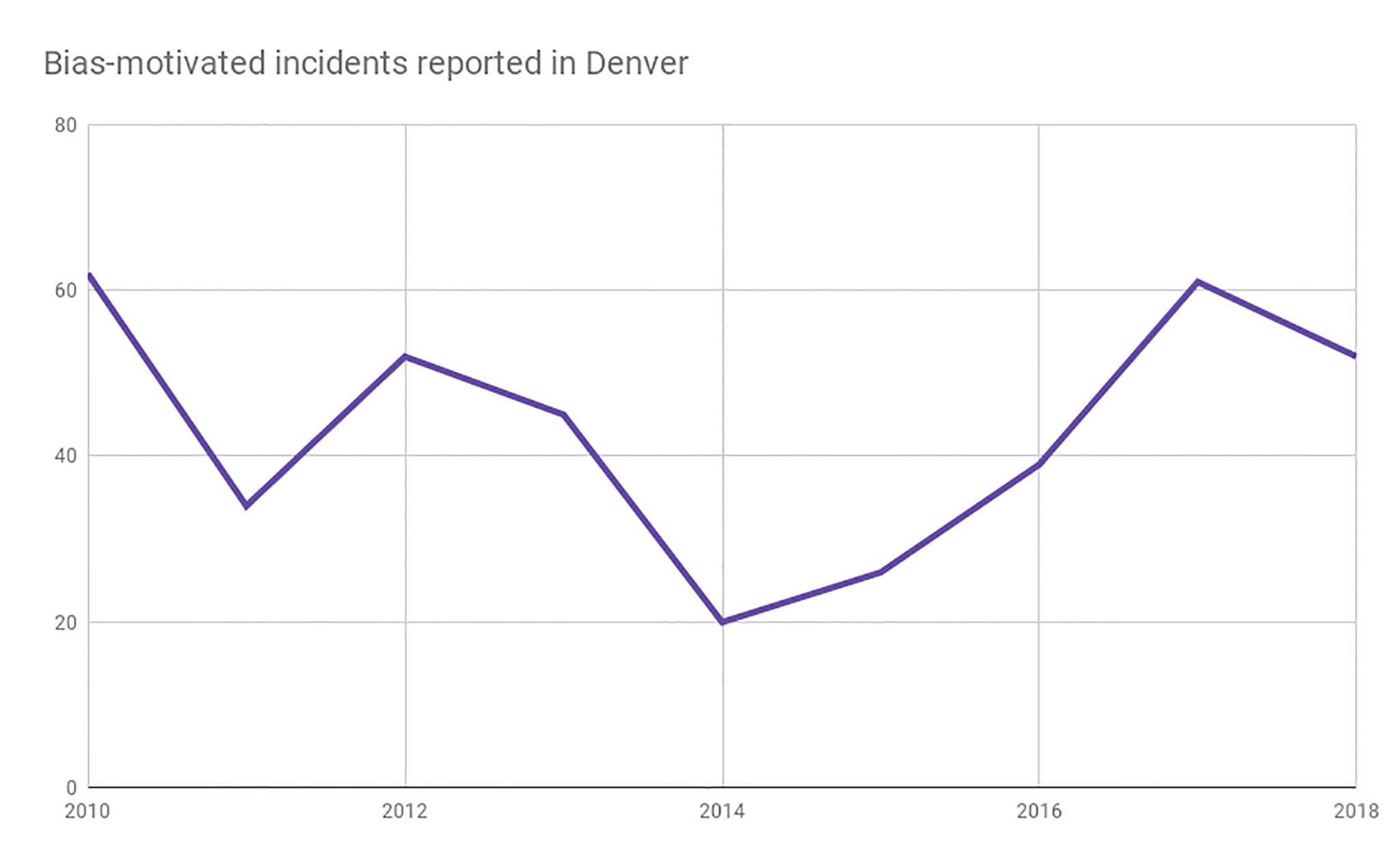

Denver's numbers show peak reports of these crimes in 2010 and 2017, about 60 in those years. Those reports dip to 20 in 2014 and then rise again.

Hernandez told Denverite that the rising number in recent years is likely due to better reporting and investigation, both because the department has been working on being more engaged in this area and because they've been trying to encourage the community to be more active in reporting.

His detectives have also been going through old reports to identify hateful intent, but only in the last couple of years, so it's likely rising numbers have come from those retroactive investigations. They've also recently placed an emphasis on crimes against transgender people. There were virtually no incidents recorded against that community until 2016; since then, there have been about five reports per year.

Leslie Mongin, who works with a Denver Police unit that aims to prevent violent extremism, told Denverite that there's "a real concern" that these incidents are "significantly underreported."

The department, she added, has been working to improve relations with communities that might not trust the police or know how to report hate crimes. Her group is currently working on a flyer to encourage reporting these incidents that will be translated into 12 languages and will likely be distributed before the end of the year.

One reason hate incidents aren't often reported comes from fear of retaliation.

"White supremacist action can have a very chilling effect," she said.

Her unit, which was funded last year by a grant from the Department of Homeland Security, aims to intercept people in the city who might be involved with hate groups before their activity rises to a level of violence. They use national data to identify which groups should be focused on.

"White supremacy is absolutely a priority," when it rises to the level of violent extremism, she said, but added that it's just one group that the police need to keep their eyes on. "There's no single profile of who can radicalize."