The groups pushing the pressure points of government agencies tasked with ending traffic deaths on Denver's streets have graded the city's performance, and let's just say Mayor Michael Hancock might be getting a call from the principal's office.

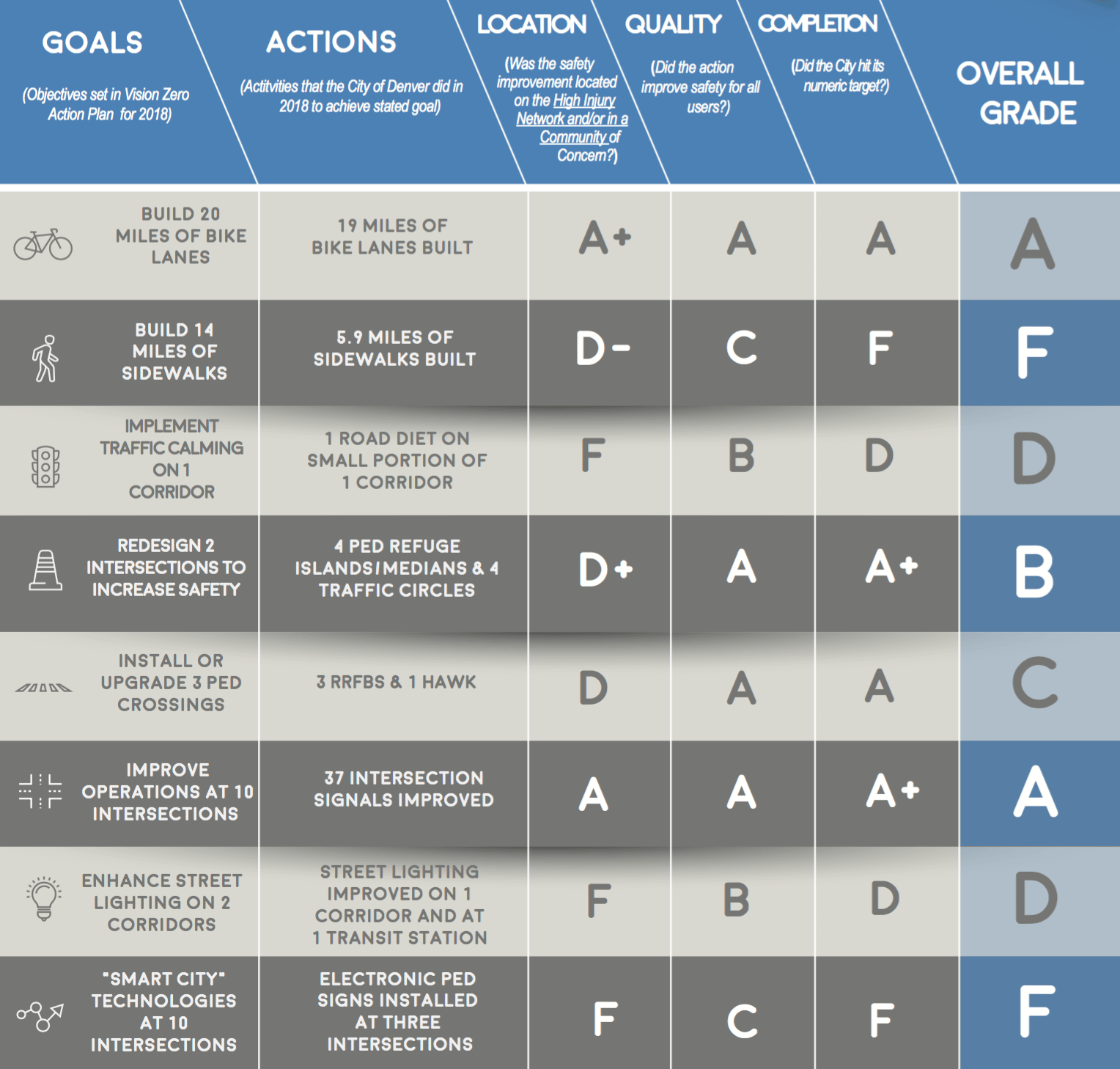

Overall, the infrastructure component Denver's Vision Zero initiative got a low C from the Denver Streets Partnership, which tracks how well the city implements projects to calm traffic and save lives.

Based on its own goals for 2018, the Hancock administration failed to build enough sidewalks and fell well short if its goal to install "smart" electronic pedestrian signals at 10 intersections, advocates found. The city also missed its target on traffic calming measures and street-light improvements.

The goal for new bike lanes and more pedestrian-friendly signal timing fared much better:

Sixty-two people died traveling around Denver last year, according to Denver Police Department figures. (Denver Public Works puts the number at 59 to align with federal reporting standards.) Of course, one traffic death is too many.

"A lot of what we're seeing is that these deaths are preventable," said Danny Katz, director of the Colorado Public Interest Research Group. "We have designed our streets in a way that too often prioritizes vehicles, prioritizes speeds, and when you design streets in that way you're gonna design them in a way where you're gonna have unacceptable, preventable deaths."

Katz spoke during a press conference on Albrook Drive in Montbello, where DPW installed a pedestrian refuge with a crosswalk and flashing lights to slow down drivers. That street treatment should be held up as an example, he said.

But even when the city installs good projects, where they install them matters. The city lost points for good projects built outside of Denver's deadliest streets or areas were income levels are low and childhood obesity is high. Health is a big deal for Pam Jiner, who runs the pedestrian advocacy group Montbello Walks.

"Montbello Walks came out of our community's need to get healthier," she said. "We are unhealthy and we need to walk to reach that goal."

In a press release sent prior to Tuesday's report card, Public Works committed to more Vision Zero stuff.

As far as engineering and capital investments go, the streets department said it would make these moves:

- Make more improvements and investments on High-Injury Network corridors

- Increase the number of dedicated left turn arrows where current traffic signal equipment will allow

- Increase the number of leading pedestrian intervals at intersections around Denver to give those walking increased visibility, so they are more established in an intersection

- Prioritize more locations for pedestrian enhancements such as Rapid Flashing Beacons and pedestrian refuge islands

- Continue to build out the pedestrian network and the enhanced bikeway network

- Upgrade street lighting along corridors to improve visibility

"This year, Denver will continue working with its local, state, and advocacy partners to educate and engage the public about creating safer streets," said Eulois Cleckley, executive director of Denver Public Works. "We'll also look at opportunities to help reduce speeds, implement enhancements to keep our most vulnerable users safe, and put our money where it matters most -- into High Injury Network corridors."

Reducing the number of people who die walking, biking and driving is a political issue.

One perceived problem with retrofitting streets to prioritize their most vulnerable users -- people walking, using wheelchairs and biking -- is that it often means slowing drivers down or repurposing road space, advocates say. Supplanting curbside parking spaces to build safe bike lanes, for example, can mean angry calls from the driving public to elected officials.

Another reason for the slow pace of change is money and personnel. The Hancock administration and Denver City Council have beefed up money for safer streets in recent years, but not to the point of rapid change. And Public Works has been transitioning since Cleckley took over to create a city transportation department.

"A transportation agency would be an awesome way to implement this stuff sooner," said City Councilwoman Stacie Gilmore. So would more money, she said.