Candidates for Denver mayor and City Council have promised for months that they will rectify the lopsided results of the city's prosperity, which has left some without homes and others without a Denver ZIP code.

Politicians want to fix things in various ways: allowing "tent cities," spiking developer fees for affordable housing in favor of physical units, wrapping mental health help and job training around homelessness services, changing zoning to diversify housing types.

The well-polished talking points at political forums get head nods and hisses from people in the audience. They identify with the growing pains caused by sudden, heavy investment in neighborhoods without policies and funding in place to prevent displacement.

Denver is short an estimated 32,000 homes to meet demand, while newly built homes for low- and middle-income locals lag behind luxury apartment construction.

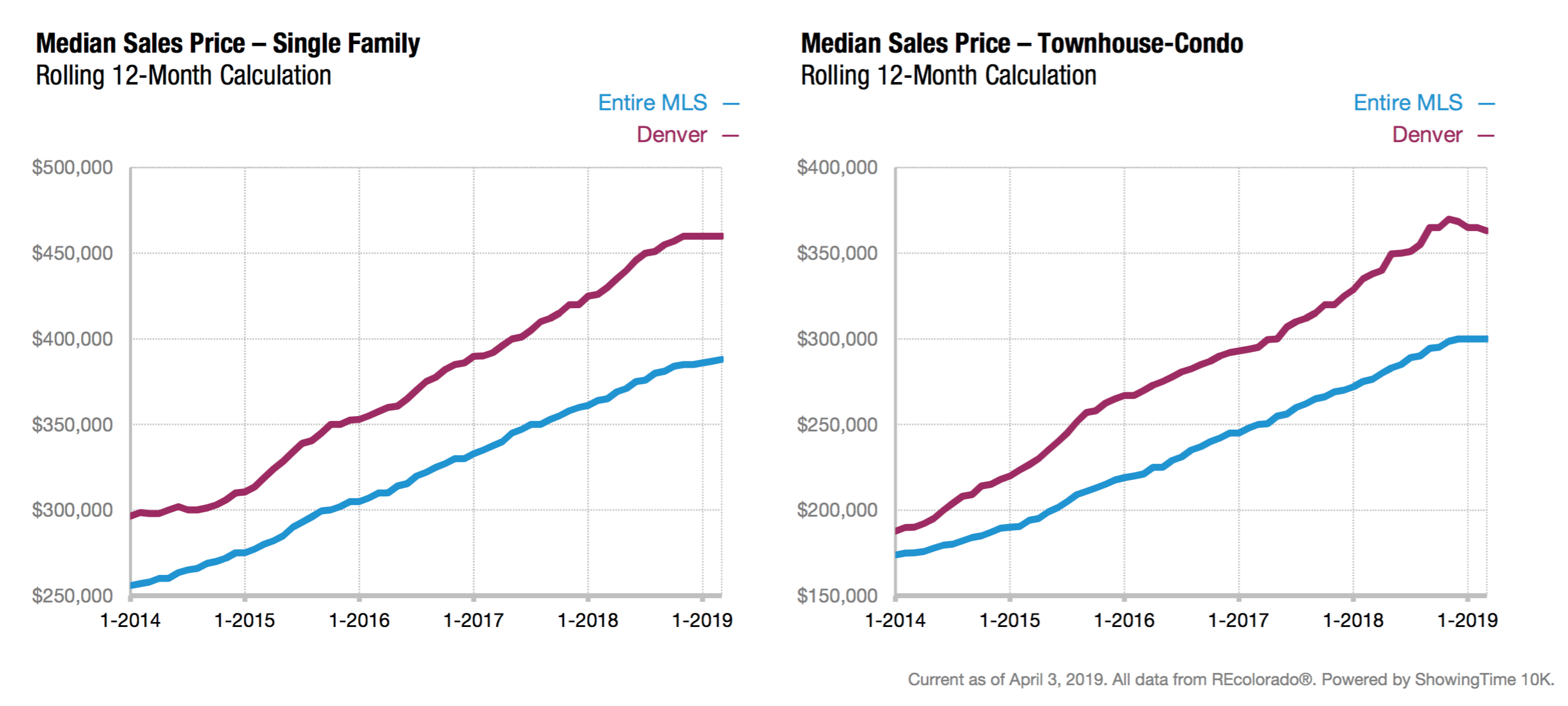

Even people with decent jobs are struggling in a market that has barely cooled. Home prices have leveled out somewhat, according to the Denver Metro Association of Realtors. That may or may not bring comfort -- the median sale price for a single-family house is about $441,000, a 0.6 percent drop in the last year. The median cost of condos and town houses sits at about $352,000, a 6 percent drop.

And while the city has services to shelter and employ people experiencing homelessness, the metro area has an estimated 5,000 living people on the streets.

Just before ballots for the May 7 election dropped, Denverite went out to talk with people about the city's growing pains. What hurts? Where? And why?

Makaia Loya, 16, moved to Denver less than a year ago and she's already had to leave.

Loya moved to Swansea after growing up in Brighton and living in Douglas County for a stint, along with her mom and two siblings. She attends Manual High School -- her third high school in three years. When the year ends, the soon-to-be senior will start all over at a school in Thornton, her new home.

"I think the hardest part is having to start over with friends and being involved," Loya said during a phone interview from Mexico. "A lot of these programs offer high-school-long opportunities. They start signing you up for more and more, and then you have to leave."

She's the kind of student that teachers -- and cities -- want. Loya mentors sixth graders. She's part of Project Voyce, a group of young community organizers. She's on Manual's student leadership team. She plays volleyball.

Loya's family's rent was raised in Swansea, hence the move to Thornton. She's happy with the house -- it has three bathrooms instead of just one -- but hates being so far from her friends and activities in Denver. Her mom drives two kids to Denver every day, then returns to Thornton for work and daycare for her son.

"We're saving money on housing, I guess, but really it's going all toward our gas," Loya said. "If the cost of living wasn't so high (in Swansea), we probably would have stayed."

Lonnie Humphries fell through the cracks after living in Denver for 20 years.

We found him talking to friends outside the Denver Rescue Mission's Lawrence Street shelter where Denver police officers stare from across the street or while looping around slowly in SUVs.

Humphries lost his apartment eight months ago after getting priced out while between jobs. The hot market allowed the landlord to raise the rent. It went up to about $800 and he fell behind. Then it went up to $930 and he fell further behind. By the time he was evicted, he owed $1,500 in late fees alone and lacked a home while he looked for another job.

"They wanted only working people to live there so they went up on the rent without telling me," Humphries said.

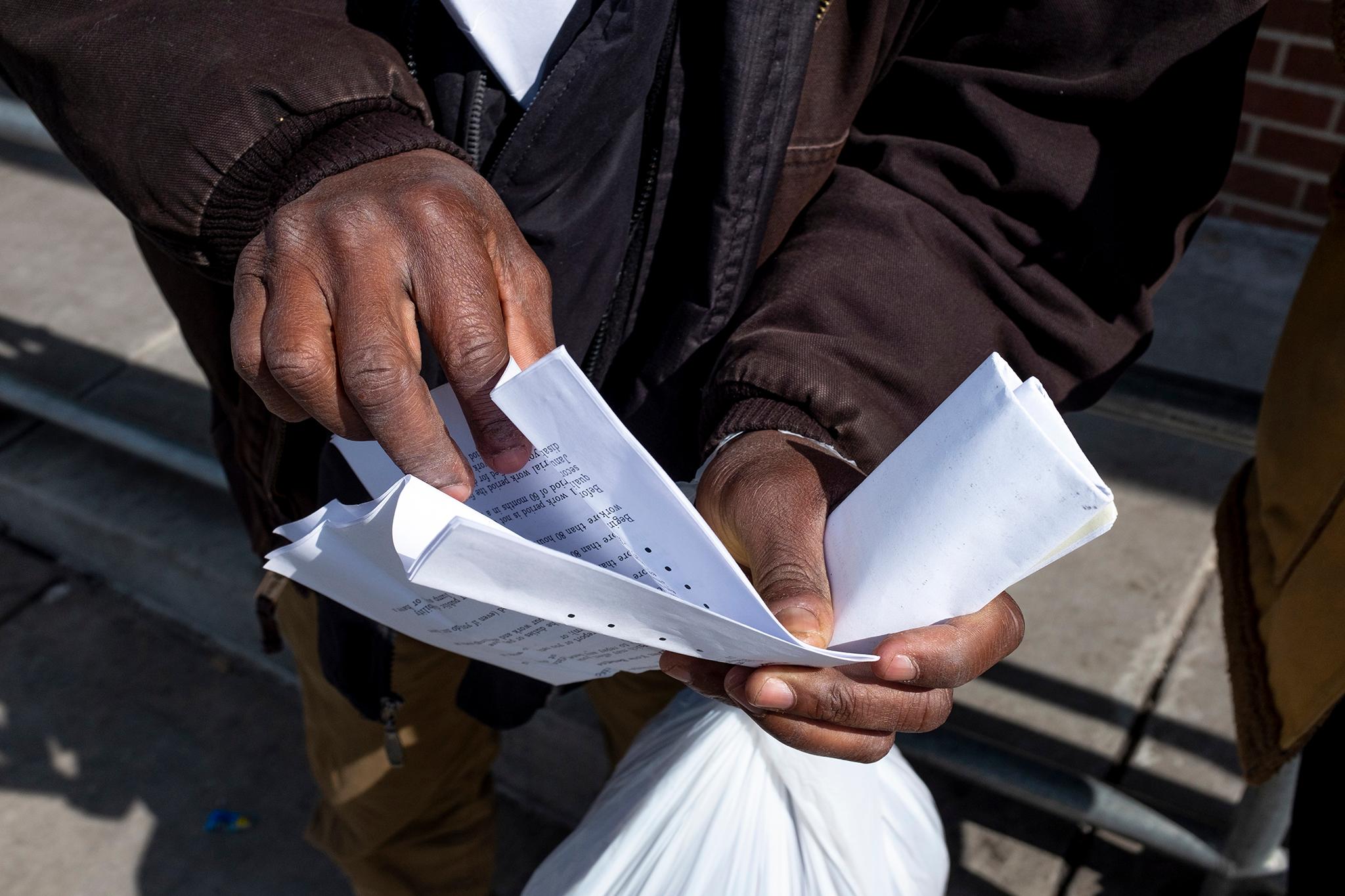

On top of his housing woes, the Social Security Administration screwed up and discontinued his disability benefits. Humphries held in his hand a folded government document titled "Notice of Revised Decision," which means the feds admitted their mistake. But he's been waiting for weeks to get his SNAP card loaded with funds, and continues to do so.

Humphries needs one thing, he said: subsidized housing.

Lindsay Taylor bought a Highland house in 2010 but couldn't last in Denver's market.

Taylor, a musician, used to be the marketing director at Swallow Hill Music. She and her husband bought a 700 square-foot duplex for $195,000 and sold it in 2017 after getting divorced, she told Denverite at the time. It was worth at least $330,000, which convinced Taylor that she had enough money for a down payment on a new home.

But she did not. House prices rose about $50,000 in three months while she searched for a new home. Despite their good jobs, Taylor and her boyfriend searched and searched in Denver and the mountains with no luck.

"We left, which is sad because I made Denver my home and was planning on making Colorado my home for a lifetime, and that just became an impossibility," Taylor said.

They now live in New Mexico, because that's where they could afford to buy.

Thomas Allen is without a home. He'd rather be without a home in another city.

Allen, for lack of a word that defines his anger more succinctly, is pissed. He didn't talk so much as yell.

"Bro, where we gonna go for $1,800 a month?" Thomas said outside the Mission. "Where is anyone on these streets down here supposed to go?"

Of course, Denver has a network of shelters -- he uses them -- but Allen, 50, says there isn't enough "structure" in terms of behavioral health and job training services.

Still, the city's growing pains hit him hardest in the way he is stigmatized. He feels constantly watched by police, he said, and feels demeaned by store owners who won't let him use their bathrooms.

"I'm spending my cash to go to your store, you're gonna tell me I can't use your facility?" he said. "You don't even know if I'm homeless!"

Allen said he wants to see city-sanctioned communities of tents allowed. Better, he said, would be subsidized housing on the parking lots that surround the Mission. Regardless, he plans to move on from Denver this summer.

So if there are growing pains, what's the aspirin?

The city's first-ever affordable housing fund was chapter one. The doubling of said fund was chapter two. Pretty much every candidate for mayor and city council say they've sketched out chapter three -- check the Denverite voting guide for details.

City Councilman Paul Kashmann, who is running unopposed, shared his remedy. It consists of rearranging the city's shelter system to welcome everyone, whether she has a boyfriend, a kid, a wife or a dog with her. It consists of amplifying community land trusts, which place ownership in the hands of the people who live there in perpetuity. And it consists of the city playing a bigger role in housing, an arena dominated by the private sector, he said.

"I think the city needs to look for the opportunities to acquire properties, to give us added ability to control prices of housing," Kashmann said. "Affordable housing is like all of our other social safety nets. The market demands its profit, we give the market its profit, and the housing prices come down because we subsidize it with our tax money. We don't let people die on the street, we subsidize their health care in the emergency room. We don't let people starve to death, we provide food stamps or similar programs.

"I'd rather the city consider taking a more active role on its own rather than subsidizing market profit."