The managing director of a new Denver nonprofit sat in what looked like the waiting room of a well-appointed law office and gestured down Gaylord Street toward Colfax Avenue.

It's a part of town where it's easy to spot people on the street who look like they don't have anywhere else to go. Lola Strong said her The Other Side Academy Denver -- which is, in fact, set to move into a red brick mansion that used to be law offices -- could be the place for some of these men and women.

"They need us," Strong said Wednesday. "They're lost. Some of them have got no place to go."

Strong has brought a strategy for supporting people like herself -- who have been incarcerated or struggled with addiction or homelessness -- to Denver from San Francisco by way of Salt Lake City.

"We're not hopeless," Strong said. "If you give people an environment that's conducive to hope, a place that they can stay long enough, that's tough enough, with the right kind of people who can mentor them, who speak their language ... change is possible."

Strong helped start Salt Lake City's academy, which was toured in 2016 by participants in a Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce Leadership Exchange program. Among the Denverites who were impressed by what they saw was Mayor Michael Hancock. He asked his business community to help replicate a model he has called a way "to break that very expensive cycle that you and I pay for from the streets to jail, from the streets to detox, back to the streets to jail."

Andrew Schmidt, a partner in Denver's Core Contractors Roofing Systems, led the effort to raise almost $3 million for the Denver academy. A ribbon cutting was held last week on Gaylord Street.

Strong has been a heroin addict and homeless. In 2008, facing what would have been her fourth prison sentence in her home state of California, she asked a judge to try something different. Instead of prison, she wanted to go to Delancey Street.

Delancey Street started in San Francisco in 1971. Residents spend at least two years preparing for independent living by learning social and other skills and later gaining work experience. Restaurants, trucking companies and other businesses run by Delancey Street residents fund the programs, which have been established around the country. Residents pay nothing.

The judge agreed to send Strong to a Delancey Street in Los Angeles. She stayed five years, the last three as a volunteer manager.

"My new drug became helping other women, helping other people," Strong said.

After leaving Delancey Street, Strong managed a medical practice and, reconnected with relatives, worked in her family's vacation rental business. She had a good life living near the beach, she said, but was not entirely satisfied. She realized what was missing when she learned of plans for a Salt Lake City version of Delancey Street being hatched by a Utah writer of books about business strategies and philosophies.

In their 2007 book Influencer: The Power to Change Anything, Joseph Grenny and his co-authors Kerry Patterson, David Maxfield, Ron McMillan and Gareth Jones had presented Delancey Street as a model for transforming businesses and other organizations. An article on The Other Side Academy's web site describes Grenny receiving a letter from a Utah County Jail inmate. The inmate had read about Delancey Street in Influencer and wanted Grenny to help him get into the program. Grenny, whose brother was a county prosecutor, managed that, along the way introducing the Delancey Street idea to officials in Utah.

Grenny and his wife Celia led the effort to bring the Delancey Street vision to their home state, bringing in Strong to help start what they called The Other Side Academy. After Denverites showed they were serious about having an academy here, Strong was named its managing director.

Denver Economic Development & Opportunity Executive Director Eric Hiraga took part in a ribbon-cutting ceremony on Gaylord Street last week. DEDO provided $450,000 in Community Development Block Grant funding to help The Other Side Academy buy the mansion.

Not everyone needs The Other Side's structure, Strong acknowledged.

"This is not housing first," Strong said, referring to an approach that emphasizes that some people need to be housed before they can address problems such as unemployment or addiction.

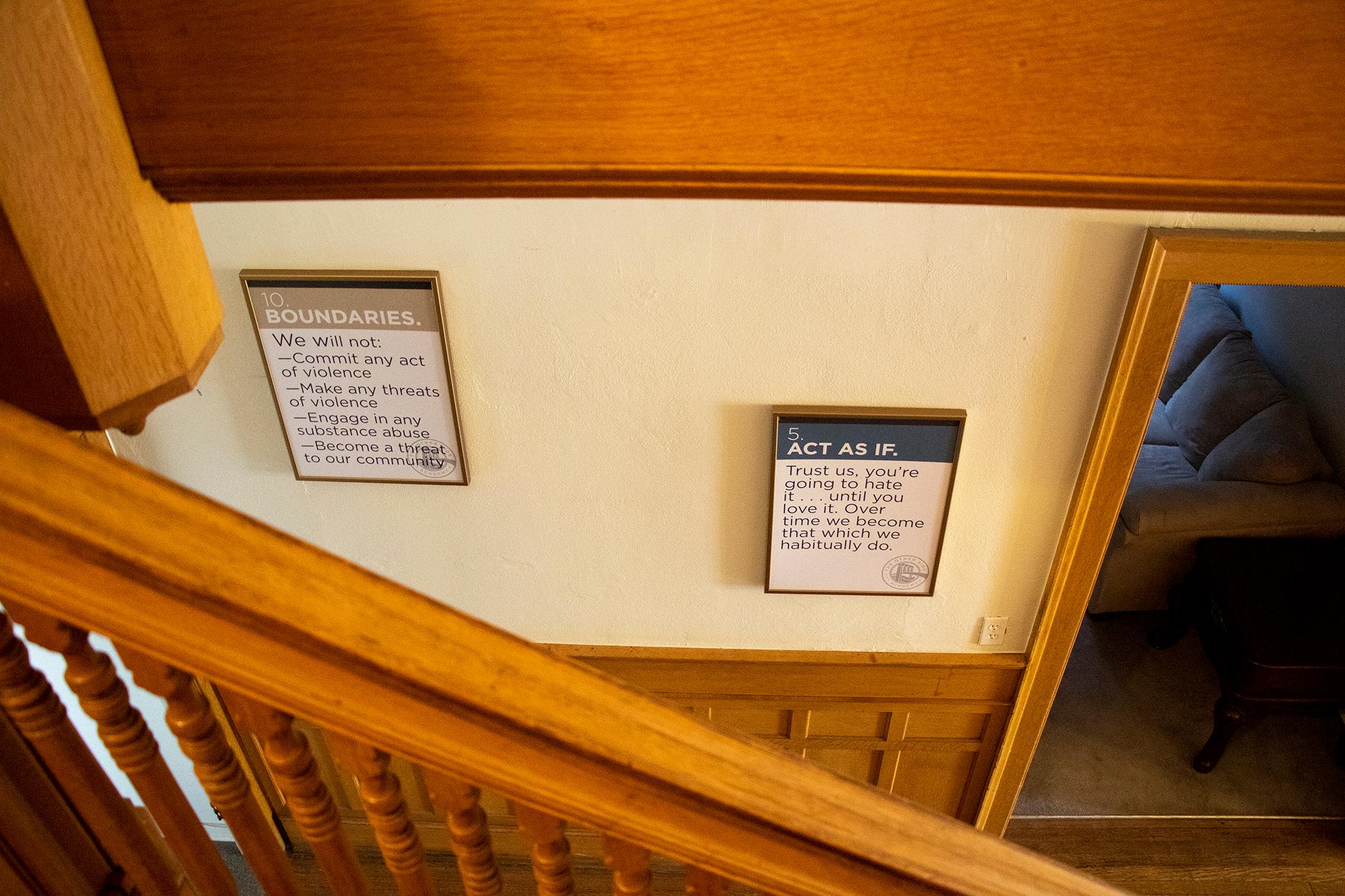

"This is changing behavior first," Strong said, describing candidates for The Other Side as having lost connections to community and needing to re-learn habits as simple as good grooming.

"You need to get back to basics first," she said. At The Other Side, "you learn how to work. You learn how to be a team player."

The Gaylord mansion can house at least 30 people, with one live-in staff member for every 10 students, as residents are referred to in The Other Side. Participants are expected to support each other, sharing skills and perspectives.

"It's a peer-run community," Strong said. "We like to grow our staff members from within."

Strong and other former residents who are now staff transplanted from Salt Lake City have already started the moving company that will fund the Denver program. They're working out of temporary headquarters on Federal Boulevard while awaiting the zoning change and building permit necessary to move to Gaylord Street, where some bunk beds and office furniture is already in place.

They've started interviewing prospects, spreading the word in part through the criminal justice system. Friday, a team from The Other Side headed to Grand Junction to pick up the first Colorado student, a man facing drug charges. Strong said her goal was to bring in about three new residents a month, saying slow growth was most sustainable.

The Other Side will consider walk-ins. Strong said if someone were to come in from Colfax, she might ask if he or she has children and would like to be a better parent.

She's looking, Strong said, for "someone that can say, 'I'm a mess. And I need help.'"

Corrects amount of city funding for the Denver academy's property purchase in previous version. The city contributed $450,000.