Members of Campbell Chapel traditionally celebrate Fourth of July with residents of the apartment building for low-income families that their African Methodist Episcopal church owns.

This summer, smoke from grills drifted into blue skies over the party on the City Park West block where both the church and the apartments stand. Children took a break from the bouncy castle to gather at the feet of Mildred Cockrell. They listened to her stories about her late father DC Coleman and the members of his congregation who helped him build the 24-unit complex named for him. Cockrell still has a shovel used for the ceremonial groundbreaking of Coleman Manor, which was completed in 1969 and where rents are subsidized with federal funds.

"Maybe if others see what we're doing, see how we're living, we may encourage someone else to follow us," the 82-year-old Cockrell said.

The Interfaith Alliance of Colorado has been working since March of 2018 to persuade places of worship across the state to help address the affordable housing crisis. The idea has been pursued in the Bay Area and other parts of the country, with some coining the term YIGBY, for "yes in God's backyard," as an answer to NIMBY -- "not in my backyard."

The University of Baltimore's Schaefer Center for Public Policy and the real estate nonprofit Enterprise Community Partners developed a Faith-Based Development Initiative several years ago and recently began offering a certificate program to show faith groups how to build affordable housing.

In Colorado, the Interfaith Alliance's Congregation Land Campaign isn't urging churches, synagogues and mosques to buy land, as Campbell did decades ago when real estate was cheaper. Instead, the campaign is asking houses of worship to devote -- either by selling at a below-market price or donating -- underutilized property to houses for the poor and working class.

As the Interfaith Alliance tries to scale up the concept, it's worth looking back to see what can be learned from the experience of Campbell and others.

"It's unaffordable to build affordable housing these days," said Nathan Davis Hunt, director of economic justice for the Interfaith Alliance and an organizer of the land campaign. "We need to look for creative ways to remove expenses."

Hunt said a single unit of housing in a multifamily complex costs $275,000 to construct. Twenty percent of that cost is the land -- which churches have in abundance in the form, for example, of parking lots that are used only on weekends. As congregations dwindle, those lots aren't filling up like they once did on Sundays. Gardens and schools and other accessory buildings also could become sites for homes.

"The core thing for us is (that) faith communities have this asset that is a key part of the solution for affordable housing," Hunt said. "Being able to take out a big chunk of the costs can ease the burden."

Clergy and parishioners who are unsure that applying for tax credits, championing rezonings and maintaining plumbing is what they should be doing might be interested in what Jennifer Leath, the young minister of 133-year-old Campbell Chapel, has to say.

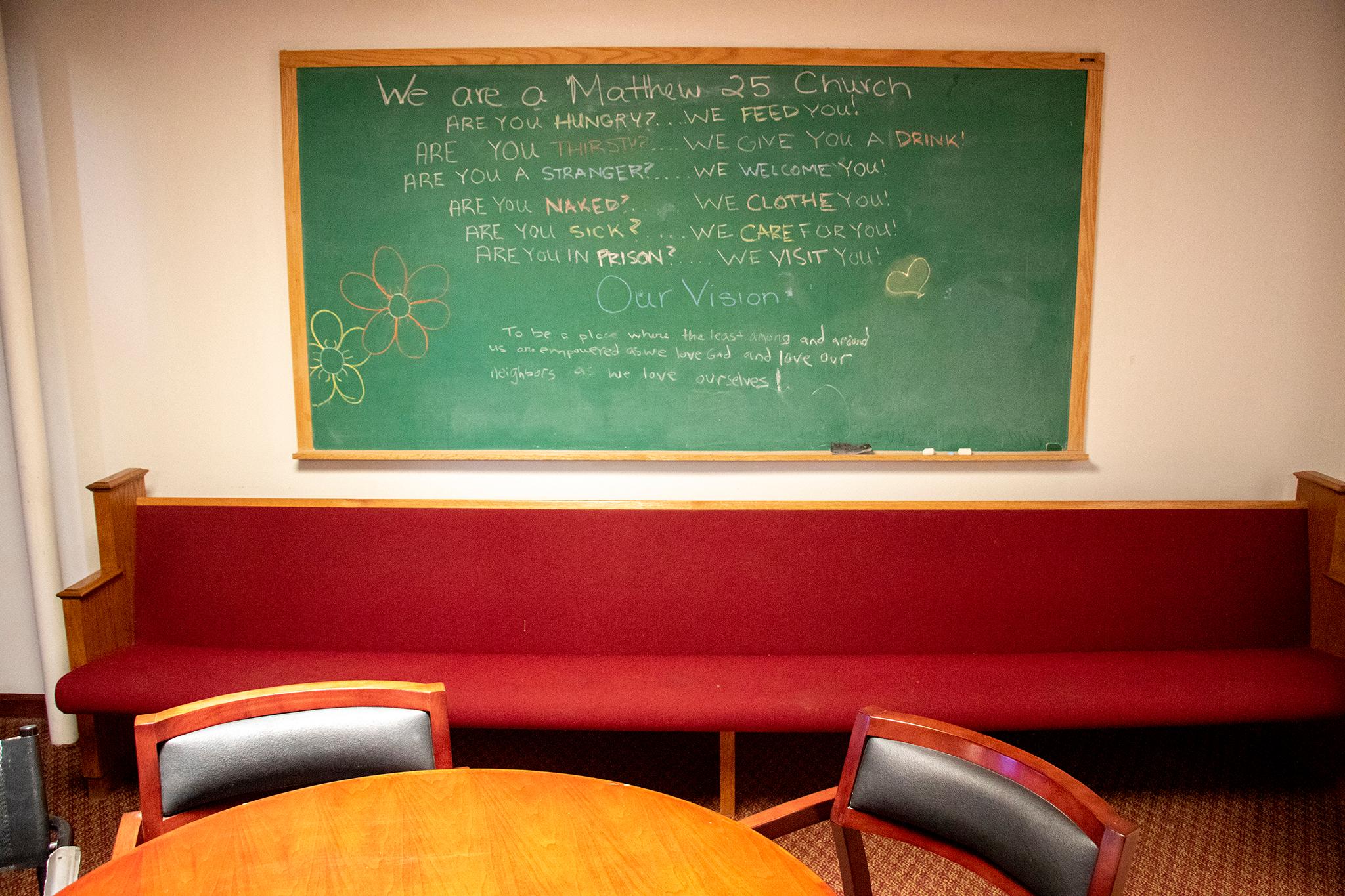

"We should strive to be a Mathew 25 church," Leath said, referring to the Bible chapter that includes the verse: "For I was hungry and you fed me. I was thirsty, and you gave me a drink. I was a stranger, and you invited me into your home."

To Leath, "housing is one of the ways to fulfill that mandate."

Building housing is of particular importance in the black community, said Leath, a fifth-generation African Methodist Episcopal minister.

Her church's leaders, she said, have long seen the importance of owning "property in a country where we have not always been able to own property, where we ourselves have been property."

She looks for inspiration to the late James Cone, a leading black liberation theologian since the 1960s and 1970s, when the Campbell parishioners were building housing. Cone, she said, "came from a church, came from a place that was saying, 'We have to creatively, innovatively work for the betterment of our communities where we are."

In a changing neighborhood like City Park West, that can mean helping families who are struggling economically stay housed where they are.

"We have a vested interest in this community. And, to God be the glory, we have property," said Leath, who is also an assistant professor of religion and social justice at the Iliff School of Theology, where she directs the social justice and ethics degree program.

It's not just liberation theologians who are interested in housing. Cheesman Park's Warren Village, a supportive housing complex that opened in 1974, was the brainchild of an obstetrician and gynecologist, Myron Waddell, who persuaded fellow parishioners at Warren Church that mothers and children needed subsidized homes to lift them out of poverty.

The effort can be extensive. Catholic Charities of Denver, an arm of the Archdiocese of Denver, has a dozen complexes in the city and others across the state for people who cannot afford market rate housing. Sometimes it's just a room for a few nights. Family Promise of Great Denver works with congregations who create private or semi-private spaces in church meeting or class rooms to shelter families in crisis.

Saint Francis Center and Saint John's, Denver's Episcopal Cathedral, last year completed a project that is similar to the Interfaith Alliance model, but was independent of the Congregation Land Campaign. Their Saint Francis Apartments at Cathedral Square offers 49 units and support services for people who have recently experienced homelessness. It's also an example of how the faith model can mean infill a city where land close to its center is particularly scarce and expensive.

Saint Francis Center, established as an Episcopal Diocese of Colorado ministry in 1983 and later as a nonprofit, has offered shelter, employment and other services to address poverty and homelessness. In 2010 it opened Cornerstone Residences, with 50 units for people transitioning out of homelessness.

"We need to have more housing. Or we're going to continue to see people dying on the streets," said Tom Luehrs, Saint Francis's executive director.

Luehrs said when he mentioned a few years ago that he wanted to expand on Saint Francis's housing offerings, he found clergy at Saint John's were thinking along similar lines. Saint Francis was able to bring the knowledge it had gained navigating tax credits and other financing strategies. And Saint John's had a parking lot near the cathedral just off Colfax in Capitol Hill.

"Since we've been through this a few times, at least we know what the potholes are and what the challenges are," Luehrs said. "For the churches, the (faith) communities, you've got to applaud them. Because it's stepping into the unknown."

When Campbell built Coleman Manor, the congregation included real estate agents. The late husband of Lula Mae Twiggs, who is 91 and still a Campbell member, was a church trustee at the time. She said the real estate agents helped manage the purchase of what was then a vacant lot to build the housing, which was not just for church members.

"I saw there was really a need for it," Twiggs said. "Housing was beginning to get short and hard to find."

Leath, Twigg's minister, said Campbell has relied on professional property managers to run the neatly kept complex.

"I'm an ethicist, not a real estate guru, not a housing guru," Leath said. "The fact that I don't know anything about it means that I have to surround myself with people who do."

Hunt, of the Interfaith Alliance, said the Congregation Land Campaign can connect faith organizations with the support they need, whether it's a developer who specializes in senior housing, a nonprofit architect, a consultant with experience responding to RFPs from DEDO -- requests for proposals from Denver Economic Development and Opportunity.

"Having the Rolodex is key," Hunt said. "It is very collaborative, the affordable housing space."

Oriana Sanchez of BlueLine Development, which built Saint Francis at Saint John's and has had a part in several other projects involving faith groups, said financing an affordable complex is complicated. Setbacks, such as failing to be awarded tax credits the first time you apply, have to be overcome.

"When you start with the mission that this is for the greater good, it makes working through those complexities a little easier," Sanchez said.

"Usually, if a church wants to do housing, in my experience, they want to provide for those who need it most," she added.

With Saint Francis and Saint John's, the target was people who have recently experienced homelessness, who often need support to avoid slipping back onto the streets. BlueLine is also building a 50-unit, low-income, permanent supportive housing complex that should open in early 2020 on land that Aurora's Elevation Christian Church sold to the Second Chance Center, a nonprofit that provides job training, mentoring and other support for people who were once incarcerated. The project is unconnected to the Congregation Land Campaign.

The connection to a group that helps people who have been in prison proved so controversial that Aurora's planning commission initially rejected a zoning change the Second Chance Center had requested. The commission was overruled by Aurora's city council at a meeting where several members of the clergy, some connected with the Congregation Land Campaign, spoke of the need for affordable housing.

"We have a crisis of knowing how to be welcoming neighbors," said Hunt of the land campaign, adding ministers, rabbis and imams who know their communities can be leaders in demonstrating "what it looks like to extend a radical welcome."

Richard Lawson, the dean of Saint John's, said he has been happy to respond when invited by the Interfaith Alliance to talk about the Congregation Land Campaign. He speaks about the importance of partnerships, saying the apartments near his cathedral would not have been built and managed without the expertise offered by Saint Francis. And he talks about the commitment of the church where he preaches to building community.

"Anything that protects and strengthens residency in the neighborhood is ultimately good for the cathedral," Lawson said of the new apartments. "Because we work with people."

Lawson and members of his congregation sit down once a month for meals with residents of the apartments. Some tenants have become church members. Breaking bread together has given homelessness, which can seem too daunting to address, a face.

"That's one of the demons of this age, that everything seems too big or too complex," Lawson said.

"We should not let that paralyze us. The small and the particular matter to God, and make a difference."

The Congregation Land Campaign has five projects for a total of 165 units in the early stages of development. The campaign and the non-profit architecture and urban design group Radian earlier this year received a $419,400 grant from the Colorado Health Foundation. They will use the money (in part) to strengthen their ability to connect faith groups to developers and housing experts.

Robin Robinson has lived at Campbell Chapel's Coleman Manor since 2011. The single mother was drawn by its affordable rents and its proximity to a supermarket and good bus route. And though she is not a church-goer herself, she has been impressed with Cambell's interest in its neighborhood. She knows church members have a food bank and regular drives to collect school supplies to donate to children at the start of each school year.

"They've been doing (housing) for awhile," Robinson added. "And they want to do more."