In 2015 Cayse Goldberg stood with Mayor Michael Hancock near the corner windows of his art gallery, Helikon, looking out toward the intersection of 36th Street and Brighton Boulevard. The street was mostly barren save for some abandoned warehouses and empty lots, and as they looked out on the industrial wasteland Hancock asked Goldberg how business was.

"I told him it wasn't great. We were on sort of a quiet road," Goldberg said. "He said it was going to get a lot busier because they were investing something like $35 million into the street. I thought that was great"

The mayor's visit to the gallery was part of a tour he took of the River North Art District, better known as the RiNo Art District. The district, of which Helikon is a member, was founded in 2005 to bring together the collection of creative businesses, artists and galleries drawn in by the affordable studio space and cheap land within the industrial areas in Five Points, Globeville, Elyria-Swansea and Cole. The district that started with just eight members had grown to 225 by 2015. Over the years they launched popular events like the annual CRUSH Walls Urban Arts Festival and helped draw many more people to the area.

Hancock's promised infrastructure overhaul on Brighton Boulevard began just a few months after he visited Helikon. Since then the city has poured in some $41 million for bike lanes, storm drains and sidewalks. The art district estimated that these improvements helped attract $850 million in private investment to the area, including bars, hotels and apartment complexes.

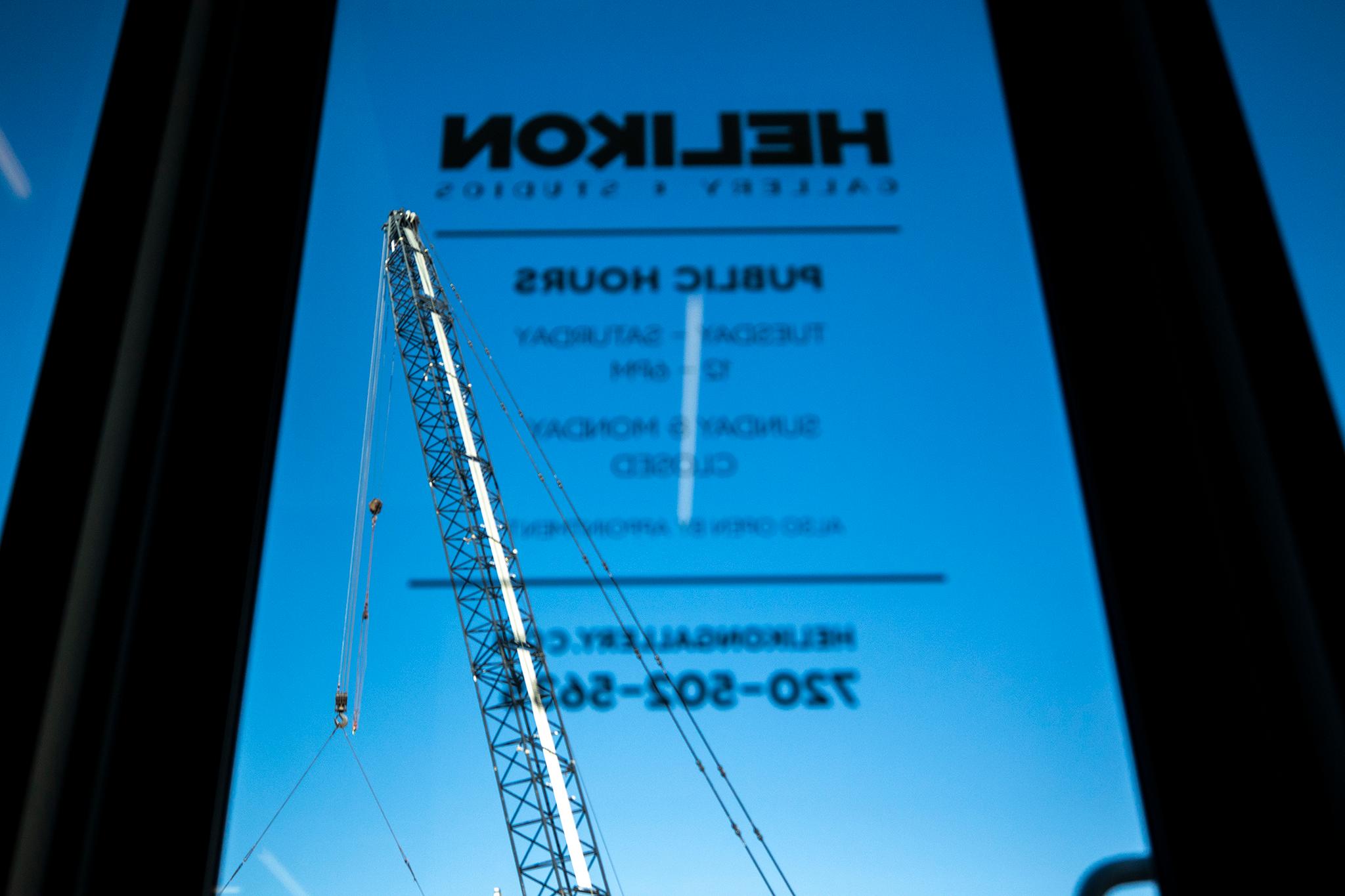

Four years after his conversation with Hancock, the view outside Goldberg's window is obscured by cranes and dump trucks. His property taxes have tripled in the last two years. Facing a $6,000 monthly tax bill that will start next year, he says he has no choice but to close Helikon.

Brighton Boulevard runs straight through the heart of RiNo, and as new businesses moved in and took advantage of the new infrastructure, they started to push out the artists that gave RiNo its name in the first place.

"It definitely changed business," Goldberg said thinking back to Hancock's words. "It killed business."

What even is an art district?

In 2000 Tracy Weil, a painter and graphic artist, bought a piece of land near the South Platte River just a few blocks off of Brighton Boulevard. At the time, Weil says, there was little in the area. His nearest food sources were 7-Eleven and Subway and he says he often called taxis that refused to come to his area.

The one thing Brighton did have, however, was artists, and more were showing up all the time. Weil teamed up with his neighbor, fellow artist and studio owner Jill Hadley-Hooper, in 2005. They founded the River North Arts District to unite the community and support arts in the area. They made themselves a rhinoceros logo and, because the district had more studios at the time than galleries, they adopted the tagline, "Where art is made."

At the time, there was no formal definition of what an arts district was. Weil and Hadley-Hooper just started throwing events and supporting the arts. The art district became an LLC and then a nonprofit. It weathered the recession and grew slowly. The RiNo Art District now comprises 475 artists and 190 studios, and it's certified as a creative district by the state. Artists undoubtedly made the area cool and appealing, and while not everyone sees the creation of the art district as the only driver of investment in the area, many believe it helped determine the flavor of the development that came.

"We created a sense of place," Weil said. "We created a world-class art destination."

Even as money pours into area businesses, the art district has done what it can to allow art to persist. In Spring 2018, the district supported a city-mandated design overlay that would make high rise developers in RiNo include a community or art element in the building. The art district also helped create a business improvement district and a general investment district in the area in 2015. The two funds are supported through additional property taxes from local businesses, a portion of which is managed by the art district and used to fund events like CRUSH Walls and curbside improvements like trees and streetlights.

The district is also working to raise additional funds for an art park on the South Platte River, which would include a community learning kitchen and affordable spaces for artists.

"What the arts district does as the most important thing is it advocates for the arts," said Jonathan Kaplan, the owner of Plinth Gallery and a RiNo Art District board member. "As an art district, we tried to stay ahead of the steamroller of development."

Change was meteoric and inevitable.

As the last undeveloped area near downtown Denver, it was only a matter of time before developers moved in on RiNo. And while many of the RiNo residents Denverite spoke to for this story did not like the development in the area, they all acknowledged that it was likely inevitable

"It's like blaming the moon for the tides," Goldberg said. "It's market forces. It's just so much bigger than anything we could be doing."

According to the art district's annual report, commercial property values in the area jumped 46 percent between 2006 and 2016. In 2017 there were 96 new projects in some stage of development within the art district's boundaries. The explosive growth signaled another inevitability: that at least some artists would leave.

Goldberg can name 10 other galleries off the top of his head that have closed in recent years.

Solo artists have had a similar exodus. Carol Waugh, a mixed-media artist with a studio in the Dry Ice Factory building, says there used to be around 40 other studios in her building. Only four are left now and she plans to leave by the end of the year.

"It's not really a place for artists anymore," she said gesturing to her window where a five-story building is under construction.

Some artists have managed to stay. Kaplan has been able to weather the increases in property taxes for the Plinth Gallery. He appreciates that he can now walk to the grocery store, but laments the fact that the neighborhood has lost some of its character. When he first opened in 2007, the building across the street held a piñata warehouse, a tropical fish shop and an Ethiopian restaurant.

Today, it's a seven-story office building.

"What bothers me is the insipid badly planned architecture that has no regard for our history," Kaplan said. "There seems to be a preponderance of large boxes going up."

So, where is the art made?

A shiny metal warehouse wedged near the rail lines on Wazee Street has had a trajectory like many in the RiNo area. It started as an industrial warehouse used for glass manufacturing and car storage. In 2010 it was converted into Wazee Union, which rented cheap studio space to about 50 artists. Last year, the warehouse was re-invented again, this time as the trendy food hall Zeppelin Station.

To make room for the fancy cocktail bars and international fusion food stalls, the artists of Wazee Union had to leave, but unlike many other developments in RiNo, they weren't turned out on the streets. Instead, the developers of both projects teamed up to create the Globeville Riverfronts Arts Center, or GRACe. The new space still had relatively low rents, but it isn't nestled among the new million-dollar developments in RiNo. It's further north, next to a salvage yard and a produce warehouse where property values remain low

When plans for the North Wynkoop development -- now home to the shiny new Mission Ballroom -- were announced in the spring of 2018, they included Artspace. The Minneapolis-based developer builds live-work space for artists around the country and was planning on dozens and dozens of units along with studio and performance space in the new RiNo development. That didn't work out. (And it's a long story.)

The trajectory of GRACe's community is no surprise to its artists. In explaining the story of their studio, Susan Dillon, the center's manager, compared artists to compost: they fertilize an area for something to grow and then they get dumped somewhere else.

"We always manage to find a place though," she said.

But Dillon and the other GRACe artists consider themselves lucky to have been offered a new space. Many artists pushed out of RiNo haven't found anything. Waugh is moving to a home studio and says she has many friends who have done the same. Others have moved out of Denver altogether, opting for one of the Lakewood creative districts, 40 West Arts District or Arts on Belmar. Some in the art community worry that as property values skyrocket all over Denver, many more may have to leave.

"Cities have to change to grow but sometimes I think we don't ask what change," Goldberg said. "Sometimes I just see all the cranes as tombstones."