Thanks to an unusual specialist at her primary care clinic, Beth Lawler Stichter got a remedy for what many may not see as a medical problem.

"I was homeless," Lawler Stichter said.

She was speaking in the office at the Salud Family Health Center's Commerce City clinic where she met with the specialist who helps at no cost: attorney Marc Scanlon.

Scanlon represented Lawler Stichter at a Social Security Administration hearing earlier this year. He explained how lingering pain following a series of surgeries and other ailments left her unable to continue working as a dog groomer. Lawler Stichter was granted disability payments that allowed her to stop couch surfing and get her own housing.

Across the country, hospitals and clinics are integrating lawyers into their medical practices.

They've begun seeing, for example, that a doctor's prescription could only do so much for patients with no homes where they can refrigerate medications that need to be kept cool.

In that vein, Lawler Stichter's doctor had referred her to Scanlon, one of two full-time lawyers who have established Medical Legal Partnership Colorado as part of Salud, a group of clinics serving low-income patients. Lawyers on clinic staffs have taken landlords to court to force them to address lead or other environmental problems that were making children sick, and helped families navigate benefit-bureaucracies to get food stamps for nutritious meals.

Pia Dean founded Medical Legal Partnership Colorado in 2015 after a 30-year career with a top Denver firm, Holland & Hart. Dean calls her office at Salud a "legal clinic in the middle of a medical clinic."

"We consider ourselves a full partner to the (medical) providers here," Dean said. "I think it's just one more arrow in the quiver of an integrated medical team."

Scanlon was a University of Colorado law student interning at the Medical Legal Partnership at its founding and has been there since. When at home discussing work with his girlfriend he refers to patients, not clients. He said his girlfriend, who is also a lawyer, gently corrects him: "Marc, you're a lawyer, not a doctor."

According to the National Center for Medical-Legal Partnership at The George Washington University, more than 300 hospitals and clinics have developed a legal element to their programs. They operate in 46 states. In a report this summer, the Colorado Health Institute said medical-legal partnerships were among the "practical options" to address the impacts that housing access -- or lack thereof -- have on health.

Stephanie Perez-Carrillo, a policy analyst at the Colorado Children's Campaign, hopes the Colorado Health Institute report can be used outside the "typical policy research world" to inform new ways of talking about health.

Perez-Carrillo's nonprofit is one of 18 organizations in the Health Equity Advocacy Cohort, which works to develop policies that address barriers to health like racism and lack of economic opportunity and immigration status. The cohort, which is funded by the Colorado Trust, hired the Colorado Health Institute to work with its members and others to write the report on health and housing.

"It's an exciting time to be working in this space," Perez-Carrillo said. "We know that there are challenges. But there are solutions."

Ashlie Brown, a director who specializes in health and data systems at the Colorado Health Institute, said health care providers have been seeing the impact of the housing crisis but weren't always aware of what steps were being taken to address problems.

"What folks need on the health side is better connections to all of the great work that's happening," Brown said.

Brown pointed not only to medical-legal partnerships but to initiatives to ensure housing stability for low-income families by promoting residents' communal ownership of mobile home parks, for example.

Tillman Farley, the chief medical officer for Salud Family Health Centers, is the son of two doctors who impressed upon him that health was about more than medicine.

"All my life, since I was a little kid, I've been hearing about housing, about clean living situations, about all the things outside the clinic walls," he said.

So he was ready to listen several years ago when he first heard about medical-legal partnerships from a medical student who was interning at Salud.

"When we first started this, I thought it would be the easiest thing in the world," Farley said. "That was my naivete."

Dede de Percin, executive director of the Mile High Health Alliance and a proponent of medical-legal partnerships, said funding is often a stumbling block. De Percin, whose alliance brings together health, human and social services leaders in the Denver area to improve community health, led a symposium in October to share ideas on establishing medical-legal partnerships.

De Percin said medical-legal partnerships need champions to prosper. Salud's has two, in Farley, who has a tight budget but nonetheless makes funding Medical Legal Partnership Colorado a priority, and in Dean, who works full time and has never taken a salary, though other staff are paid. The program is funded by Salud and by grants and private donors.

Dean since 2010 had participated in a University of Colorado program in which law students advised clinic patients. She saw how students rotated in and out, that volunteer lawyers weren't always well-versed in the issues, and that it was a struggle for lawyers who were not on-site at clinics to connect with patients. When that program ended in 2015, Dean moved to Salud.

"Funding is our ongoing challenge," Dean said, saying the partnership has survived because of "Salud's failure to let it die and our ongoing efforts to find ways to keep it going."

Children's Hospital offers an example of how difficult it can be to keep a medical-legal partnership going.

Annie Lee, executive director for community health and Medicaid strategies at Children's Child Health Advocacy Institute, said the hospital had a medical-legal partnership from 2013 to 2016. Its legal resources included pro bono attorneys and lawyers from Colorado Legal Services, a nonprofit that helps low-income Coloradans who have civil legal issues -- people with criminal issues can turn to public defenders.

"The need was so great that we were tapping out the resources that we had available regularly," said Lee, who is a lawyer.

Lee and her colleagues had to phase out the program.

But one critical facet was maintained: Clinics held three times a year, serving six families each session to supports parents or guardians who need to continue making medical decisions for adults and children with serious medical conditions.

Now Children's is resurrecting its medical-legal partnership, this time with a dedicated half-time attorney and a half-time paralegal instead of volunteers, a model closer to Salud's that Lee believes will be easier to sustain.

Interest in medical-legal partnerships persists because doctors and lawyers have seen them make a difference.

Salud patient Veronica Ortiz is an example.

Ortiz and her family had been coming to Salud for health care. They also had been trying to resolve legal immigration questions for Ortiz's husband Jose Prieto Torres, who had come to the United States from Mexico in 2003. Ortiz is a U.S. citizen, as are the couple's three children.

In 2016, Prieto Torres was refused a waiver, which meant he could be barred from the United States for years because he had entered illegally. The family wasn't sure why, but Ortiz thought a letter from her doctor explaining that her poor health made his presence in the country crucial would help with an appeal. When she asked for the letter at Salud, she was referred to the clinic's medical-legal partnership. Scanlon was able to help him secure a waiver on appeal and Prieto Torres went to Mexico for an interview with a U.S. consul who granted him lawful permanent residency last year. He can now work legally and will be eligible to apply for citizenship in 2021.

Ortiz said she has seen the impact on her family's mental health.

"We were always worried," she said. "It's been a lot of relief since he's gotten his residency."

"We've been coming to the clinic maybe six or seven years, and I didn't know about this program," she said. "Who's going to think that they have that?"

Ortiz has seen the difference having a lawyer can make. Many do not have representation in immigration matters.

"A lot of people don't have the money to get a lawyer," Ortiz said, calling the free legal help from Salud "really helpful."

Lawler Stichter, the woman who got help from Salud with her disability claim, had just lost her husband when she went with Scanlon to her Social Security Administration hearing.

Terry Stichter had worked in construction and car repair, but stopped as cancer weakened him. Lawler Stichter at first tried to keep working despite her poor health, then became her husband's full-time caregiver. The couple lost their home, moved in with friends and sent their teenage daughter to live with other friends.

Lawler Stichter had started applying for disability on her own before her husband's illness. She had found the process confusing and intimidating, and lost track of it as her husband's health worsened. When she came to Salud's lawyers, she had forgotten that she had appealed an initial refusal of her claim. Scanlon discovered she had a hearing in her appeal that was coming up.

"I thought, 'Boy, you're quick,'" she said, and smiled wryly.

The hearing "was right when I was in mourning," she said. "I cried a lot when I was sitting there."

Lawler Stichter needs more surgery. Now she can go to her own home to recover.

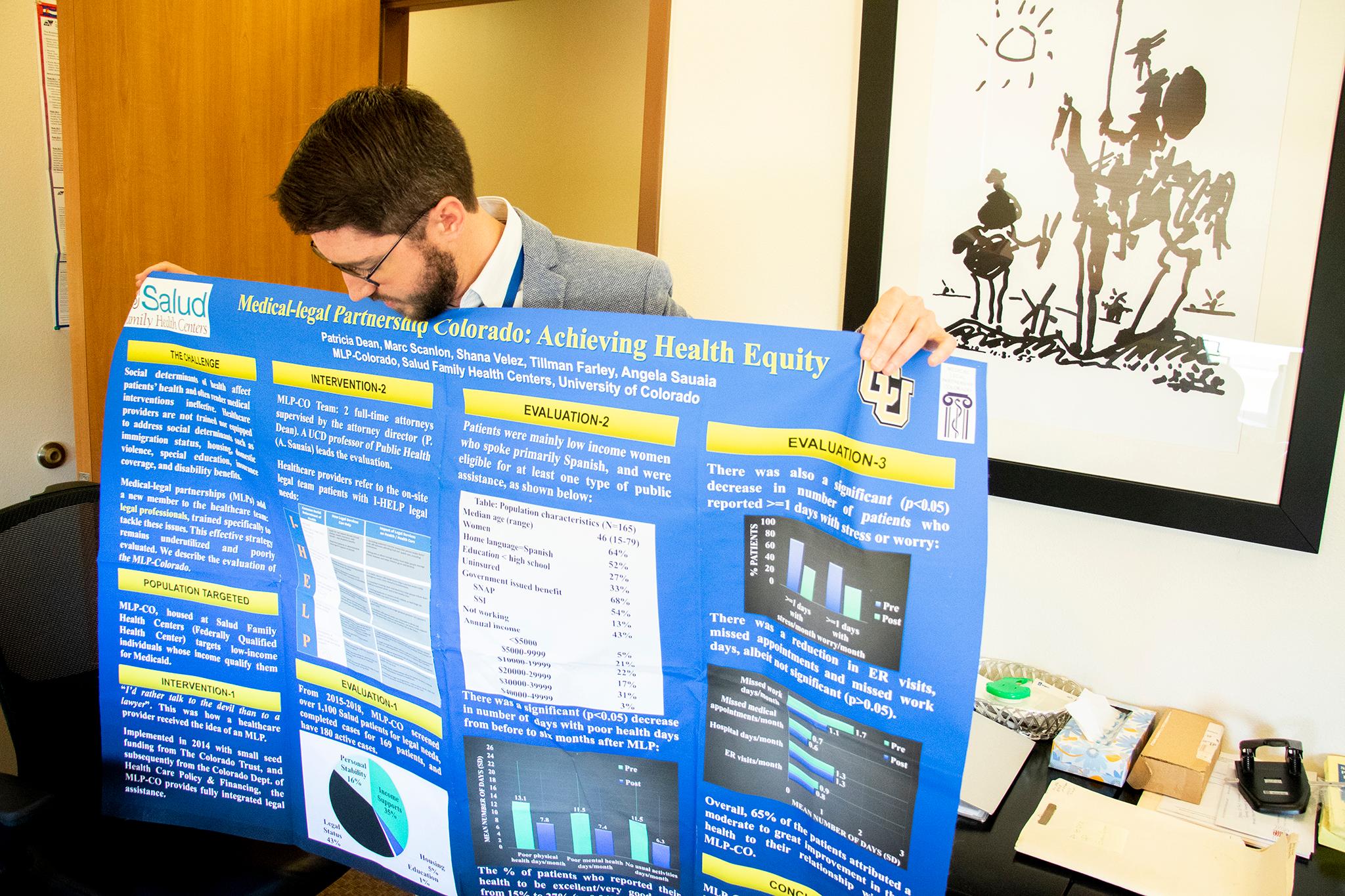

Attorney Dean said it's not just anecdotes like Ortiz's and Lawler Stichter's that give her confidence in medical-legal partnerships. Dr. Angela Sauaia. a professor of public health at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, conducted a study of Medical Legal Partnership Colorado between 2015 and last year, a period over which the project screened more than 1,100 Salud patients and completed cases for 169.

Sauaia found slight reductions in visits to emergency rooms and missed work days among people whose cases were completed. And two-thirds attributed improvement in their health to their relationship with the Salud lawyers.