More lights were strung this year than last at Sonny Lawson Park. And bigger is not better in this case.

Each of the 3,943 lights arranged in a flag-like pattern on the baseball field backstop in the park at 24th Avenue and Welton Street represents a person who was experiencing homelessness during an annual one-day survey in January.

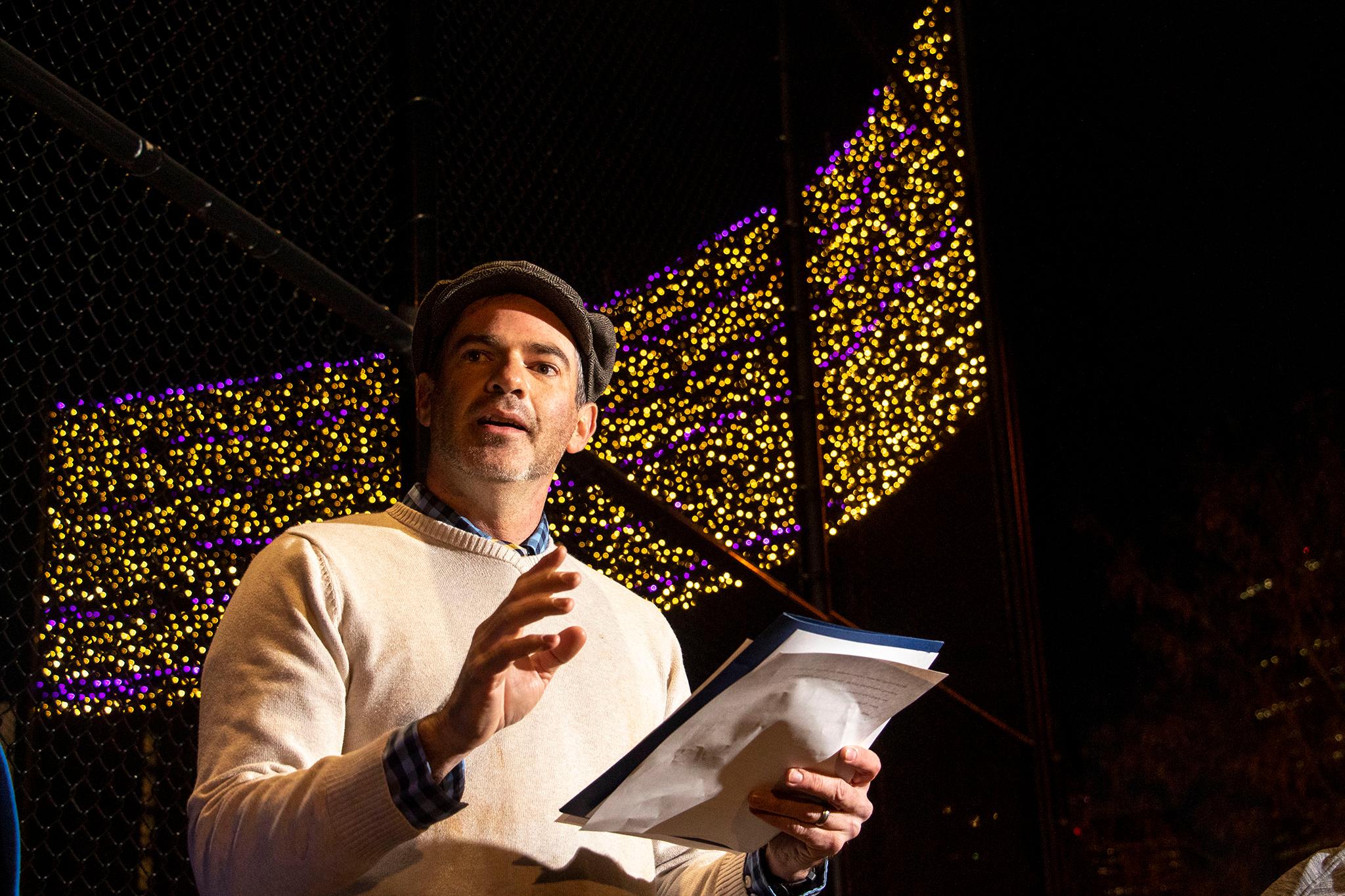

The display in Five Points, illuminated this year for the first time at sunset Wednesday, was conceived by Chris Conner, who directs the city agency Denver's Road Home, which coordinates homelessness services. The display was put up for the first time last year, when 3,445 lights hung overhead.

City housing department chief Britta Fisher said the lights show how much work still needs to be done, but added, "I'm really proud of how our service providers and our community have stepped up."

The trend has gone upward since 2016, when 3,631 people were found experiencing homeless during the annual Point in Time survey held across the country at the end of January. Fisher said that Denver has seen higher Point in Time numbers (an annual census of homelessness): 5,271 in 2012. And the city saw decreases in some categories of homelessness between last year and this, she noted.

The number of people who reported last January that they had been experiencing homelessness for less than a year and had never before been unhoused was 428, down from the 661 newly homeless counted last year.

The number of people in chronic homelessness dropped from 991 to 806. Chronic homelessness is defined as being without safe, permanent housing for at least 12 consecutive months or having experienced homelessness on at least four occasions over the past three years for at least a year.

The drops in those categories could be due (at least in part) to the city's efforts to ensure people who lose their homes are quickly identified and rehoused, or to its social impact bond program. Launched in 2016, service providers reach out to people experiencing chronic homelessness, help them find housing and provide them health, food, transportation, legal and other support. Investors who put $8.6 million into the bond will get their money back and possibly more if the program meets performance goals. The city expects to save money that in the past has been spent on jailing people experiencing chronic homelessness or caring for them in emergency rooms.

Fisher said the city is also revamping its shelter system to try to reach more people and to ensure those in shelters get support that can help them move to permanent housing. The first steps toward those changes were announced earlier Wednesday, when Fisher and Mayor Michael Hancock awarded 11 new contracts worth $6.9 million for a new women's shelter and improvements at existing shelters.

Shelley Dilly and her husband Charles Roland are among those not served by the current shelter system. The couple lives in a recreational vehicle that on Wednesday night was parked alongside Sonny Lawson. Roland said he and Dilly could not afford permanent housing and had been unable to find a shelter where they could stay together.

They came from Texas two months ago "to get a fresh start," Dilly said.

Roland has found work as a hotel security guard.

"It's not hard to get work here," Roland said. "It's the housing situation" that's difficult.