There is a saying among water managers that in the West water flows uphill to power. In Colorado, this is only half true. The water mostly flows downhill from the mountains but it does move towards the powerful population centers, farms and industrial operations that command it. And the water does not get there on its own.

Though 80 percent of Colorado's water flows in rivers on the western slope of the Rocky Mountains, about 80 percent of the state's population lives on the other side of the divide in the Front Range. In order to provide water for the cities and towns on this side of the mountains, water providers in Colorado have to pipe water under the divide. The result is an engineering marvel; a series of tunnels, reservoirs and pipelines that redirect water from rivers miles away to taps in Denver.

The history of Denver's water supply

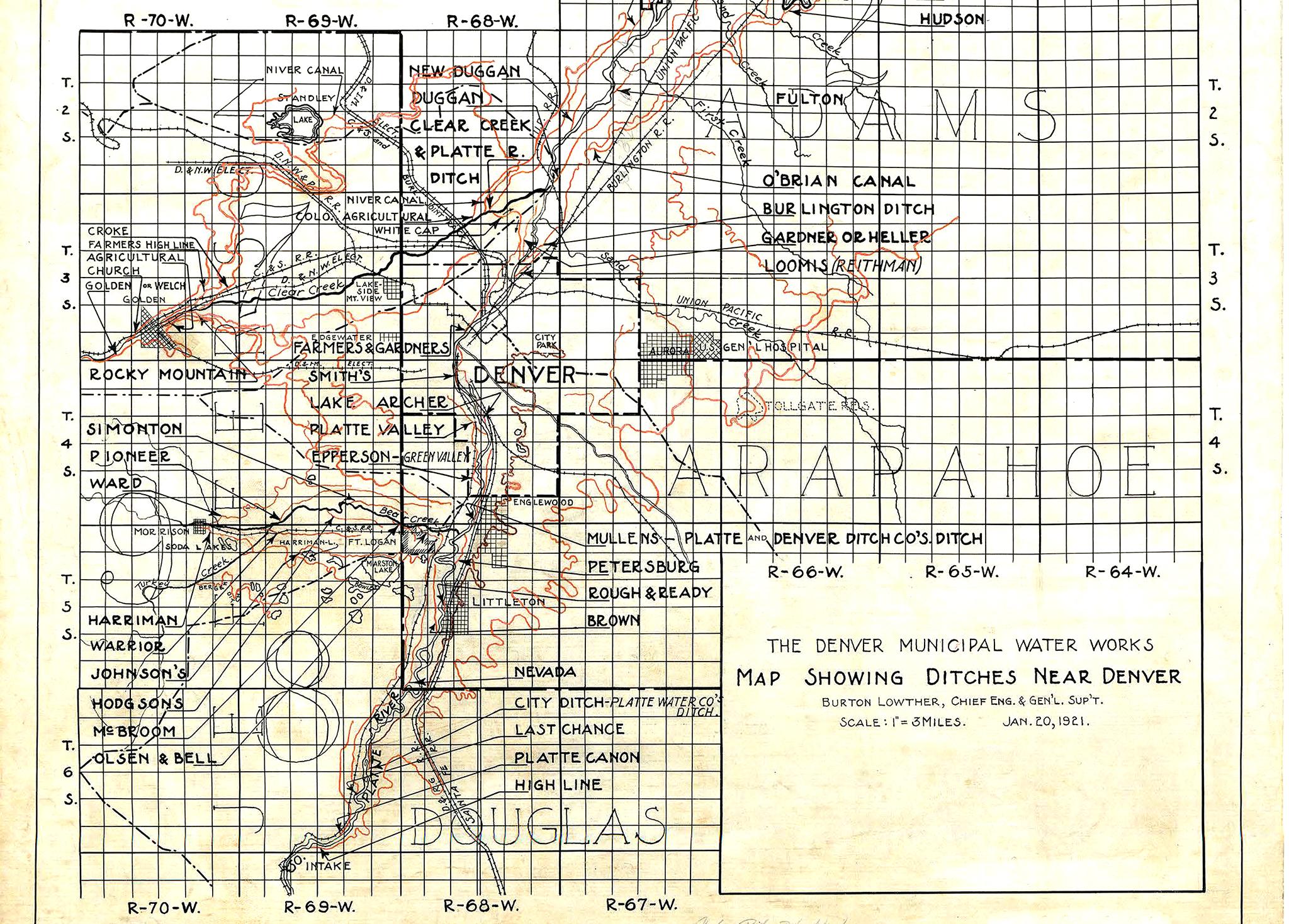

The first Denverites got their water directly from the South Platte River, using buckets to carry it home. The Capitol Hydraulic Company finished Denver's first irrigation ditch in 1867. The hand-dug, 26-mile City Ditch carried water from the South Platte River in Littleton to Capitol Hill using only gravity. The ditch still fills the lakes in Washington Park and City Park and is considered a historical landmark.

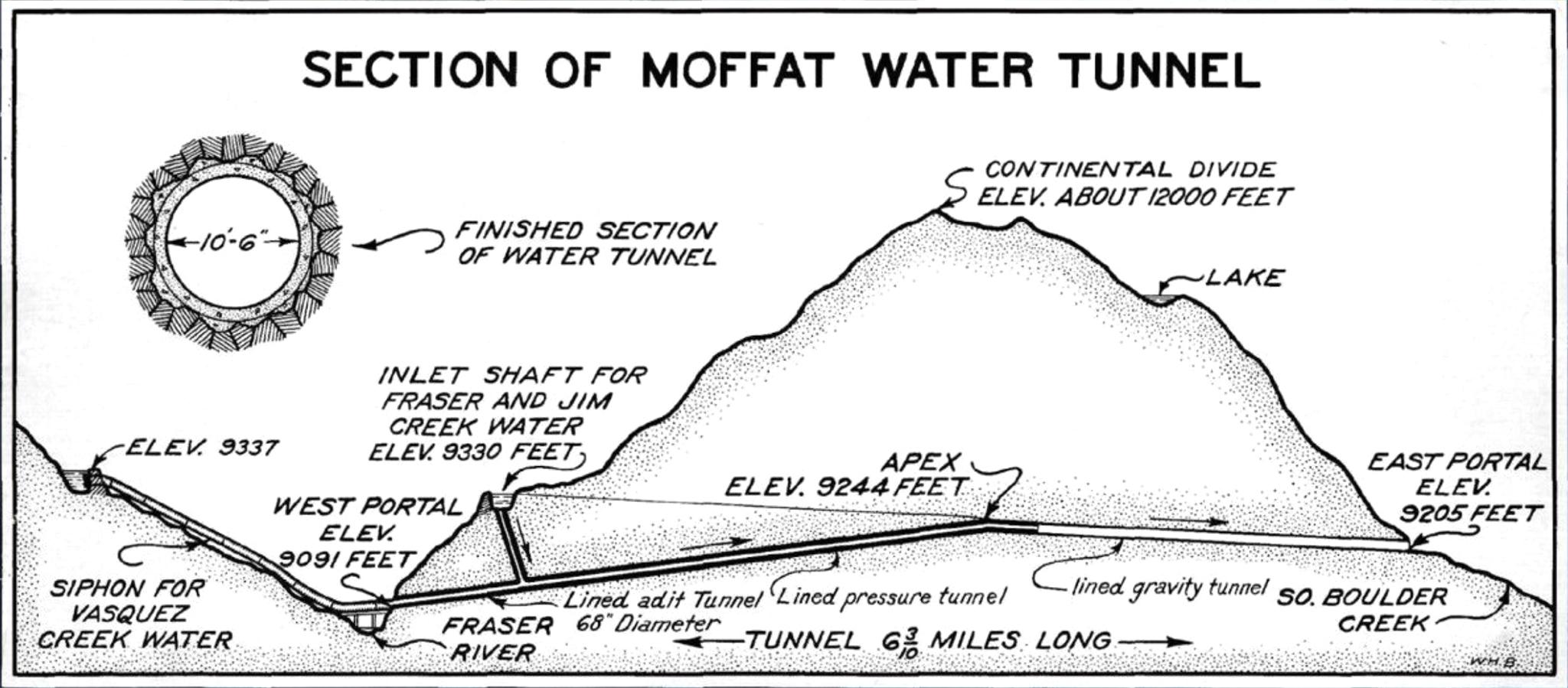

In 1872, Denver got its first set of water mains with direct delivery to homes. With the influx of water, the city slowly transformed from a dry desert to a sea of green lawns. As the population of the city grew, the South Platte became an insufficient water supply for maintaining the status quo of green landscaping. By the 1930s, Denver water providers started to look West. In 1936, Denver Water began diverting water from the Fraser River, a tributary of the Colorado River. This water was then sent through a pipeline in the Moffat Tunnel, originally built as a railroad tunnel.

Denver's water supply today

The city of Denver has gotten its water from the utility Denver Water since 1918. Today, the utility's coverage area is larger than the city limits of Denver, covering surrounding suburbs like Lakewood and Littleton. This includes about 1.4 million people who use an average of 65 billion gallons of treated water per year. For some context, that's nearly 100,000 Olympic-size swimming pools worth of water.

Most of this water goes to Denver homes and apartment buildings, and a whopping 40 percent of it winds up being used outdoors on lawns and other landscaping.

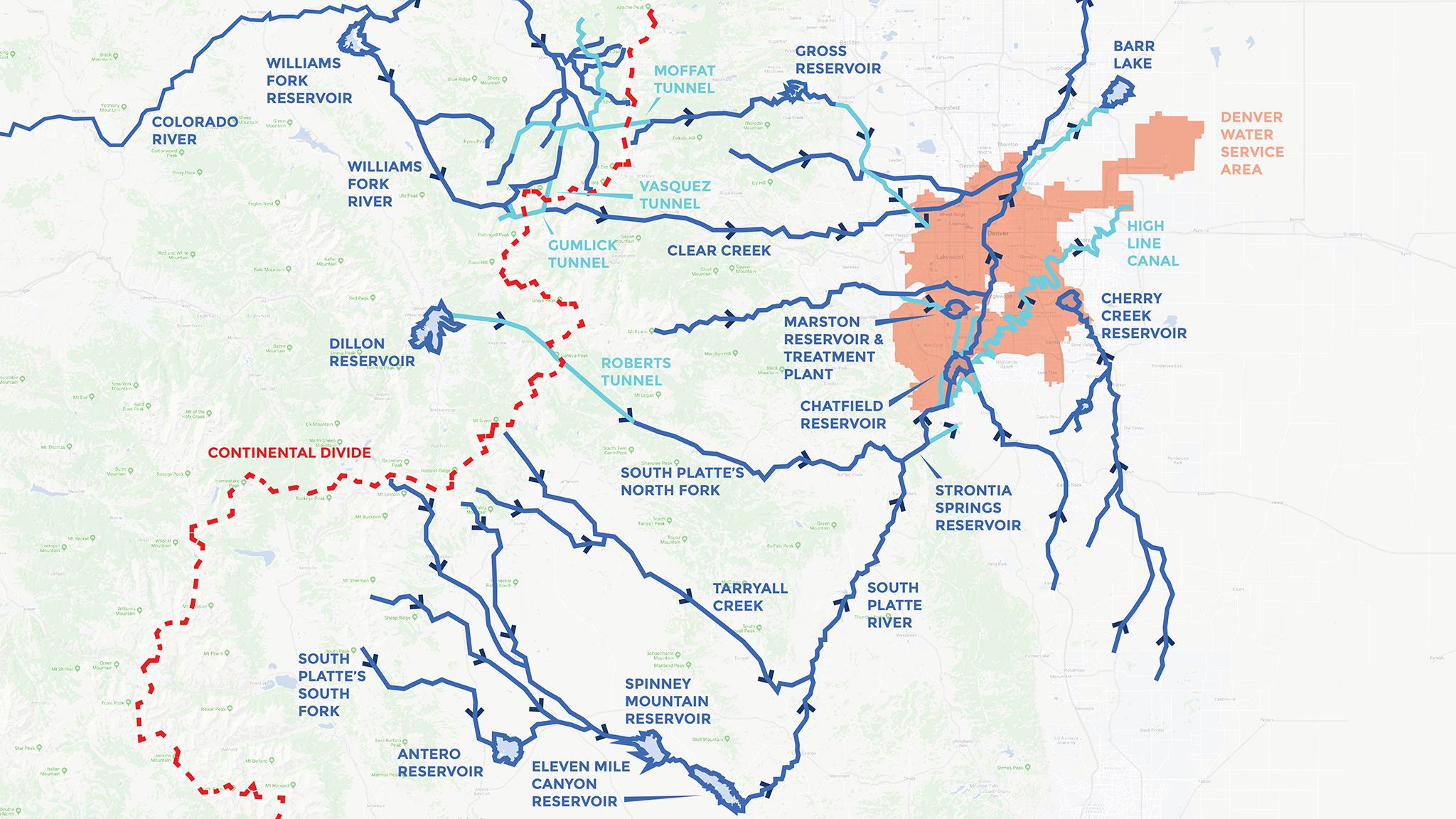

Denver water map

The map shows the system Denver Water uses today to collect water and transfer it to homes in the metro area. In any given year, about 52 percent of the water that finds its way into Denver's taps comes from the South Platte River. The Fraser River and Williams Fork River together make up 20 percent of the water supply and the final 28 percent comes from the Blue River.

These last three rivers are all part of the Colorado River system, and that water needs to be transferred to Denver under the Continental Divide. Water geeks call this type of water conveyance trans-mountain diversions. There are 24 main tunnels that bring about 400,000 acre-feet of water from the West Slope to the Front Range and provide water for both the growing cities and the robust agricultural industry on the Front Range. For reference, an Olympic-sized swimming pool is about two acre-feet.

While these diversions have been common over the last century, they've become controversial in the last few decades of drought on the Colorado River. There is debate as to whether the Colorado River system can sustain many more large diversions.

On the map, you can see Denver has two major trans-mountain conveyance systems.

Moffat Tunnel: This old railroad tunnel was the first trans-mountain diversion to feed the city of Denver. The tunnel transfers water directly from the Fraser River under the divide and into South Boulder Creek where it eventually ends up in Gross Reservoir in Boulder County. From there, the water is diverted through a canal to Ralston Reservoir, which provides water to the Moffat Water Treatment Plant.

The Williams Fork River also puts water into the Moffat Tunnel, but its journey is even more complicated. Before any Williams Fork water even reaches the Moffat Tunnel, it is first diverted into the Gumlick Tunnel, under Jones Pass then back over the divide again through the Vasquez Tunnel. The Vasquez Tunnel empties near Winter Park where the Moffat Tunnel is. By the time this water reaches Denver, it has passed under the Continental Divide three times.

Harold D. Roberts Tunnel: The Roberts Tunnel was built in 1952 to bring water to Denver from Dillon Reservoir, which sits at the confluence of the Blue River, Snake River and Ten Mile Creek. This large reservoir is Denver Water's largest, representing 37.1 of the utility's total storage capacity.

The tunnel diverts water directly from the reservoir and pipes it under the divide. The 23-mile-long tunnel sits 4,000 feet underground at some points. The pipe itself is ten feet in diameter. This water empties into the North Fork of the South Platte River and runs down the main stem of the river.

South Platte River Water: Most of Denver's water supply is drawn straight out of the South Platte River. There are three stems to the river (South, Middle and North), which all converge just south of Denver. Along the river are a number of reservoirs. When the river is running high, the reservoir's dams hold back some of the water so it can be used later on by the city. These storage reservoirs, which can be found all over the state, let water managers capture the high levels of spring runoff and distribute it well into the summer.

Water from the South Platte is eventually diverted through a series of pipelines to the Marston Reservoir, which is treated at the Marston Water Treatment Plant and sent to city customers.