If you poke around Denver's map scene long enough, you will inevitably come across Wesley Brown. He's known by some as "the map guy," and he has earned his monicker. With about 1,000 original pieces in his home, he's a prolific collector of all things cartographic.

Some of his holdings date back centuries, like a hand-drawn mariner's map of the Mediterranean from the 1500s. But Brown grew up in Denver and he has a special place in his heart for maps of his hometown. He recently gave us a tour of his map room, and he gleefully walked us through the city's early transformations as only a series of artistic maps could capture them.

"I'm really into this," he said at least once.

Here's the history of those crazy old and detailed maps that seem to be drawn from high above town.

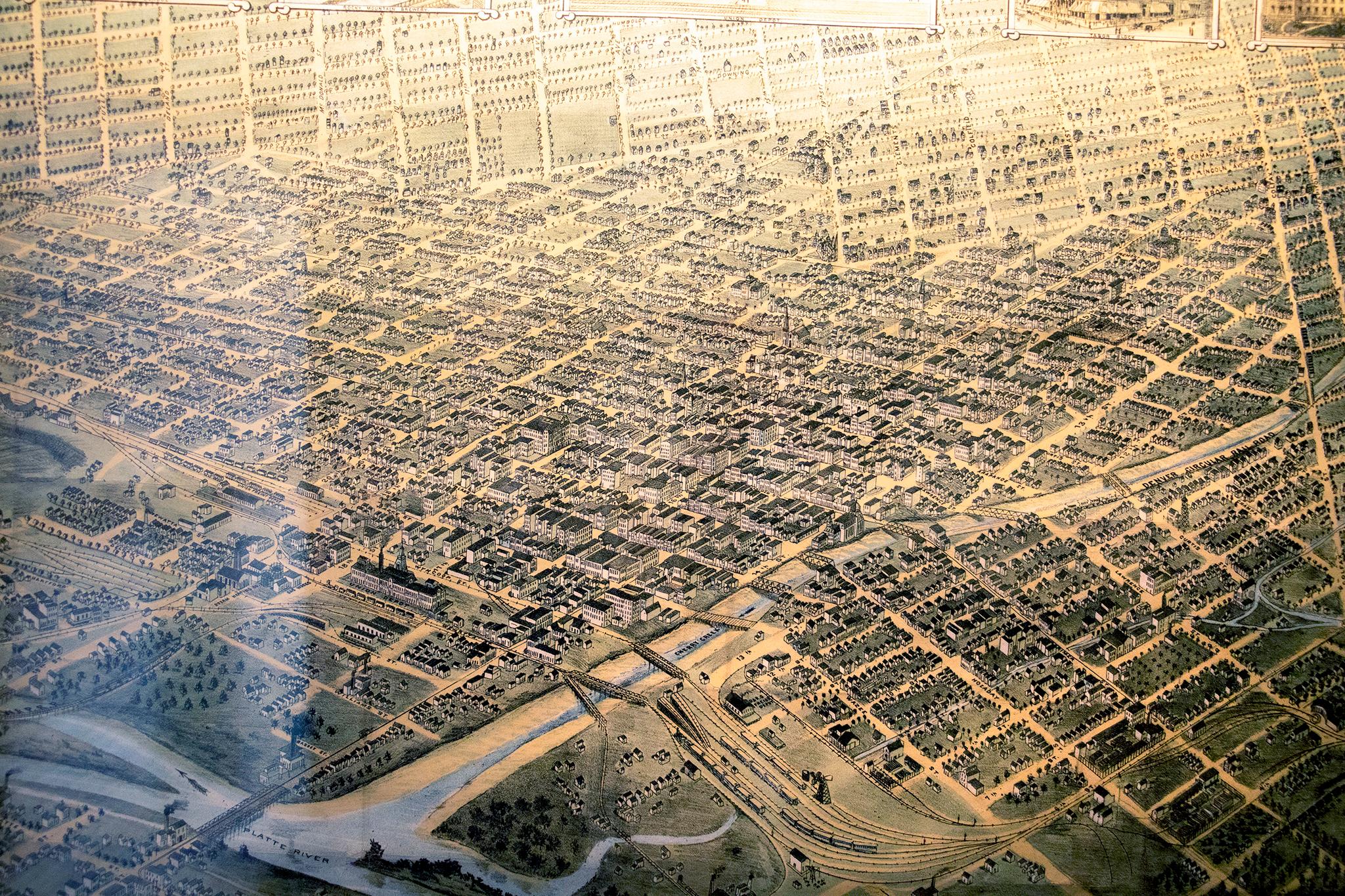

Brown's collection includes original prints of hand-drawn, "birds-eye view" maps of the city. They were all the rage around the turn of the 20th century, and Denverite writers have long fawned over their elegance.

Brown has a handful of these pieces in his South Park Hill home. Each records a separate moment in the city's history through their intricate and precise layouts.

These maps were made by "itinerant" artists who traveled from city to city selling this specialized service, Brown told Denverite. They'd roll into town and collect orders from local residents and businesses who wanted a print of their own. Some businesses paid extra to have their buildings featured in extra-detailed insets around the map's perimeter.

The cartographer would begin with a traditional street layout. Then, amazingly, he'd walk every single block to sketch every single building in the city. Those sketches were then projected and distorted in a studio to help the artist place each structure onto the street grid from an oblique, top-down perspective.

"It was going to be a commercially important document for the citizens of Denver, the business people of Denver, to try to talk about their community and show the expanses of the great buildings and how the city had grown," Brown told Denverite.

They're also handy for modern-day viewers, he said: "They're incredibly useful documents because they are accurate."

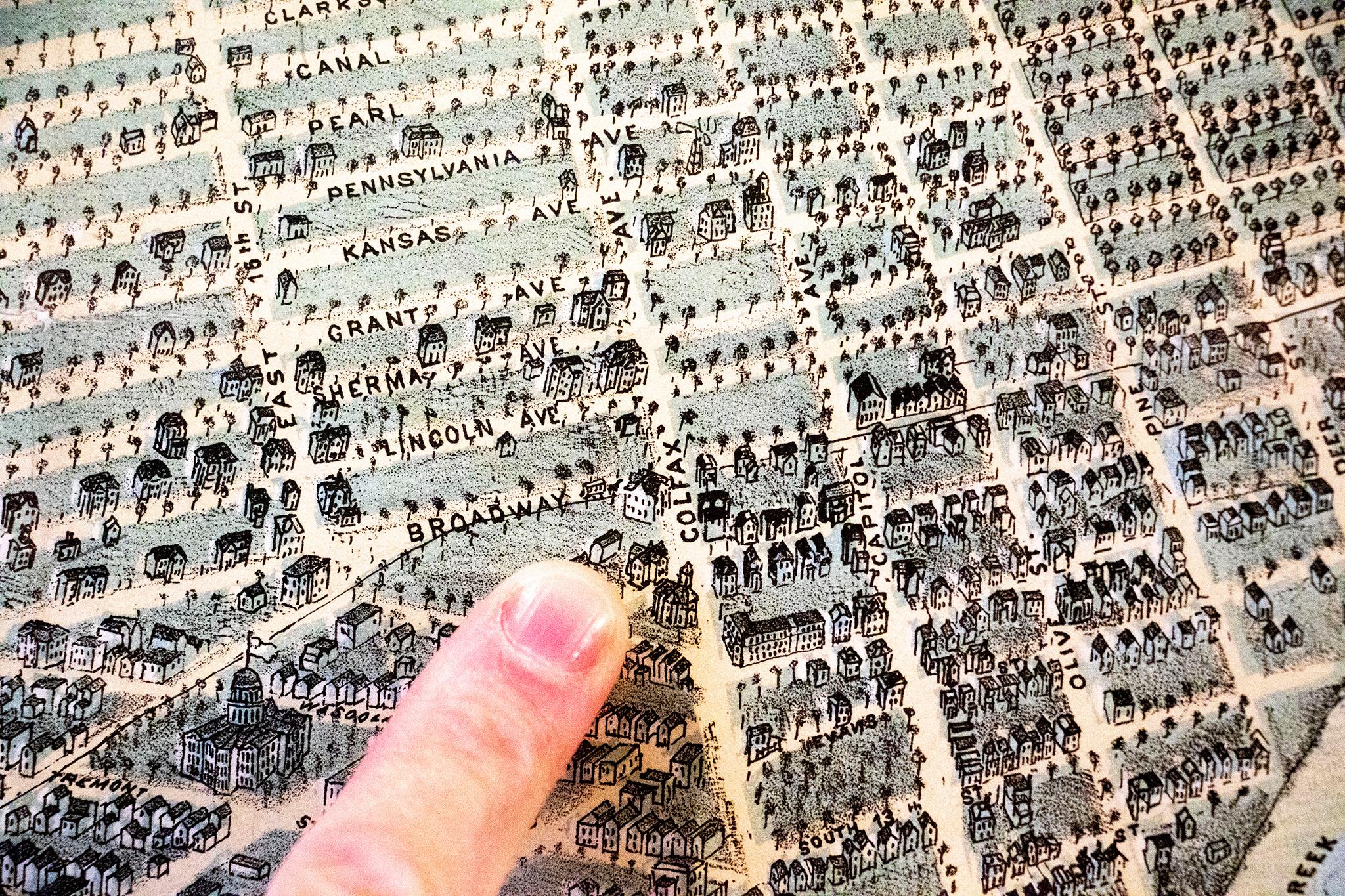

The Broadway and Colfax Avenue intersection was built in Denver's outskirts, but it became the city's heart.

The growth of the area around Broadway and Colfax is one change that's traceable over iterations of early birds-eye view maps.

The earliest of these maps was drawn and distributed in 1874. Naturally, it's situated around the Cherry Creek and South Platte River's confluence, since that's where the city's first structures were built and that was the heart of fledgling Denver's activity.

Way out in the distance, out in the middle of nowhere, is a hill labeled "cemetery" that, one day, would become Cheesman Park. Drawn below it was a meek intersection of two seemingly insignificant streets. Only one was labeled.

"This shows you the primitive first arrangement of this new street, Broadway, and this new street, Colfax, with nothing hardly there yet," Brown said. The vacant land beyond the city's early street plan, once farmland owned by Henry Brown (no relation), had only just begun to be developed.

Brown's next birds-eye map was drawn in 1882. By then, Denver's neighborhoods had expanded well beyond the hill that would someday be home to the Capitol, but the gold-domed building had still yet to be constructed. The perspective was still anchored around the confluence, but the whole view zoomed out a little bit and seemed to creep a bit to the east with the new development.

And still, he pointed out, the area around Broadway and Colfax was "just completely empty."

But Brown's final aerial map highlights a major shift for Denverites' perception of their city. By 1889, the perspective is firmly situated above Broadway and Colfax's crossroads, and the State Capitol is the crown jewel perched above the homes and factories that had appeared in places once displayed on the horizon. The Capitol building itself, however, faces the wrong way. It hadn't been constructed yet, and the mapmaker, armed only with its plans, guessed incorrectly which way it would face.

(Editor's note: Why wouldn't you guess that the Capitol would face west? Absurd.)

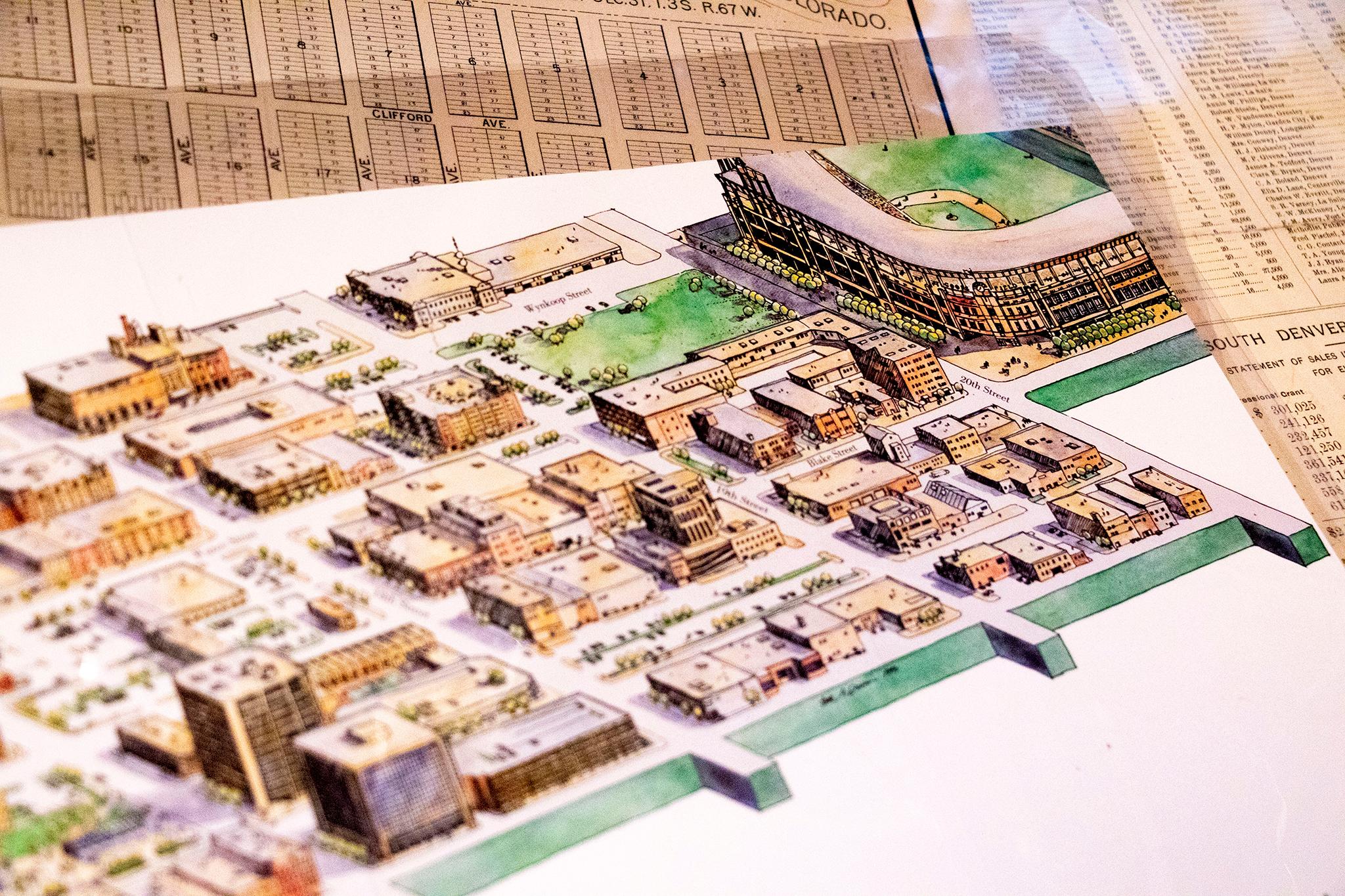

One last birds-eye view in Brown's collection was drawn in the modern era after the city's first skyscrapers had been erected. Now a home for commerce, this map again focuses squarely on Denver's downtown area, though it still used the Capitol's placement on Colfax as its anchor point.

Maps are a way for cities to telegraph their intentions and aspirations.

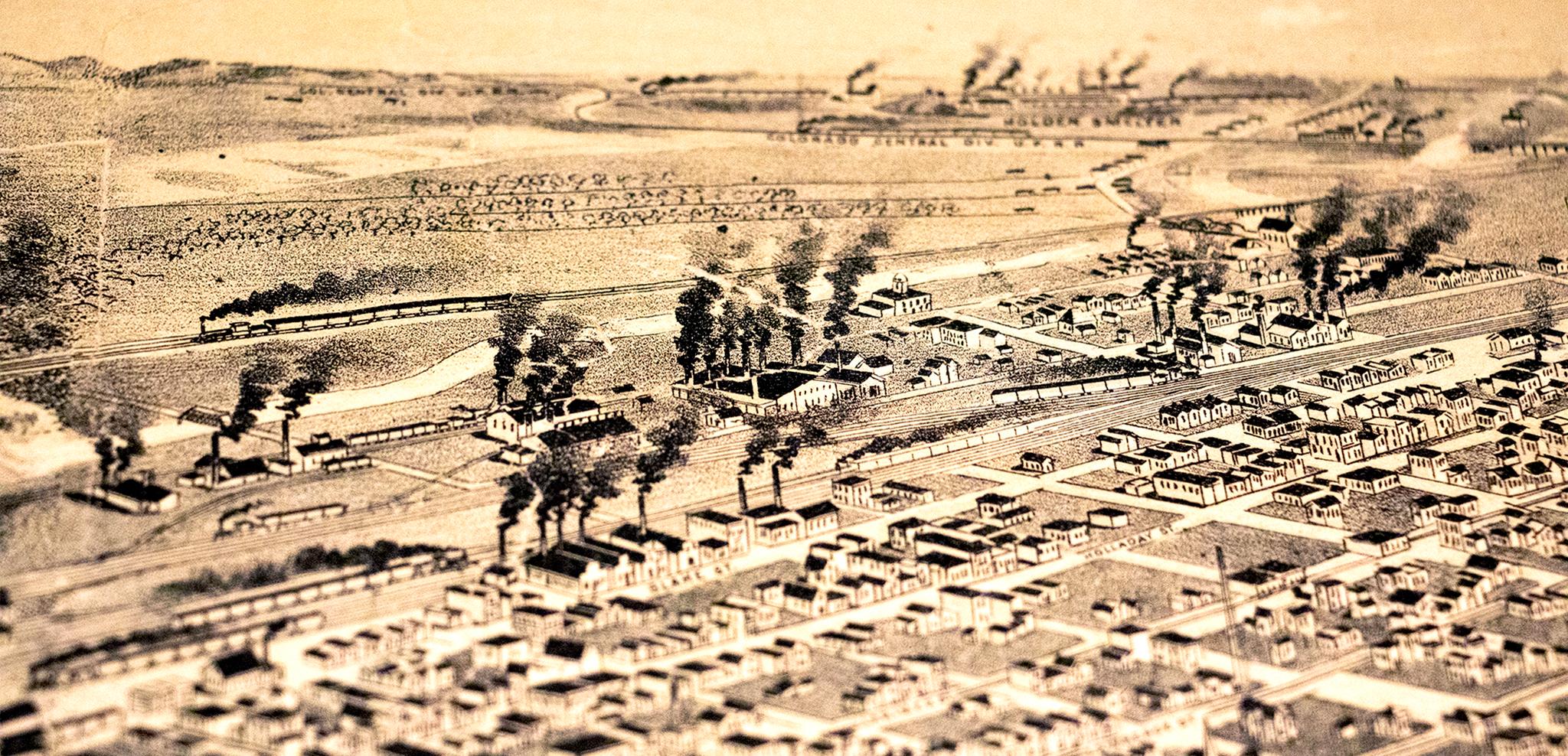

"Look at this," Brown said as he pointed at his 1889 aerial map, indicating an industrial area drawn by the river. "What's going on here is they're trying to make this city look very prosperous. Smokestacks belching smoke and industry, and this is where you want to come and move."

This is a feature that he said is shared by many of the pieces in his collection. While these maps present objective truth in the layouts of streets and where buildings reside, there's often some idealization baked in that tells us what was important at the time.

For those turn-of-the-century drawings, it was an emphasis on Denver's growth and moneyed power that meant to show the world how sophisticated this western city had become.

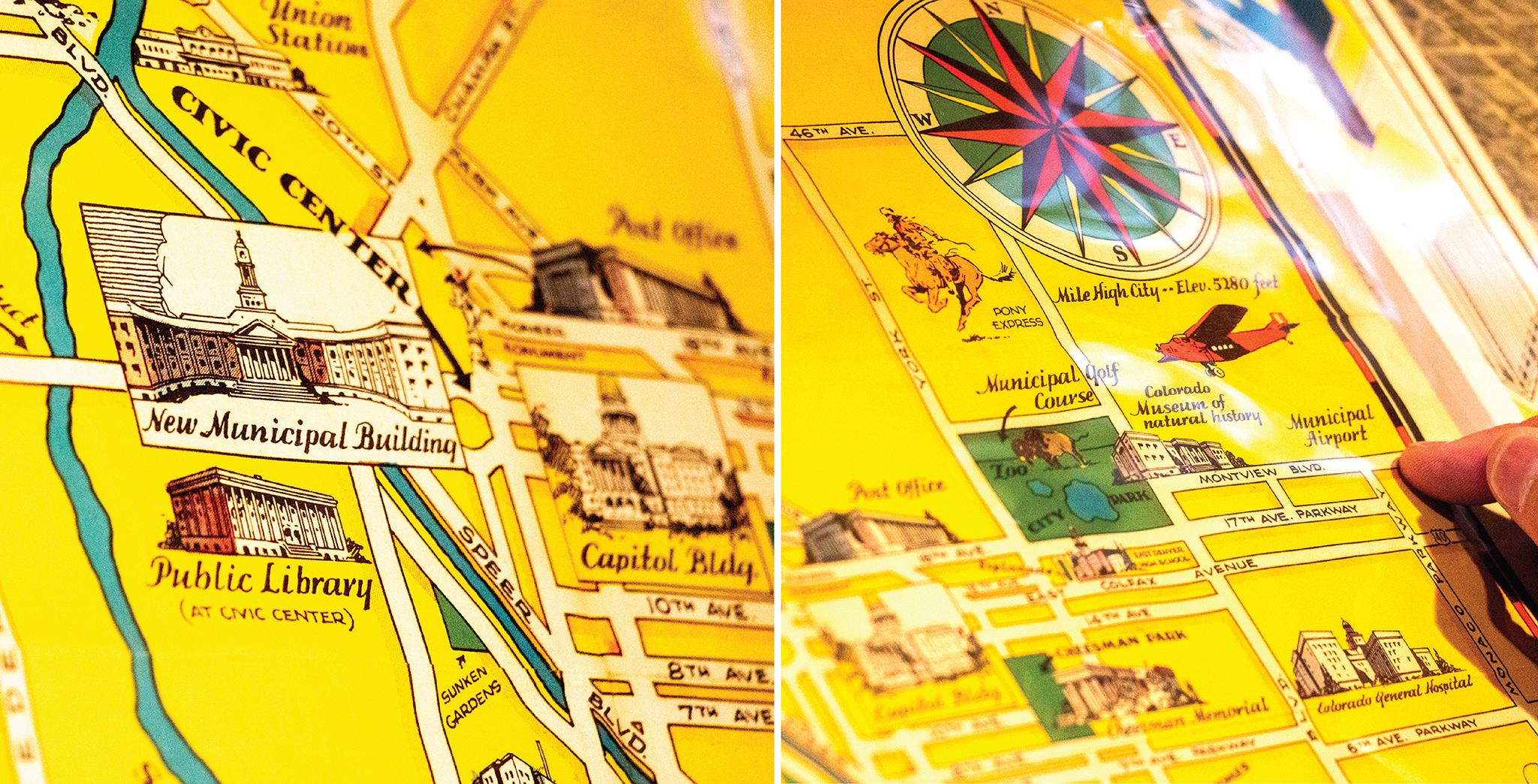

A 1930s map from Mayor George Begole's time in office shows off newer modern features, like the Denver Zoo, Cherry Creek Country Club, the new "Municipal Airport" in Stapleton and "New Municipal Building."

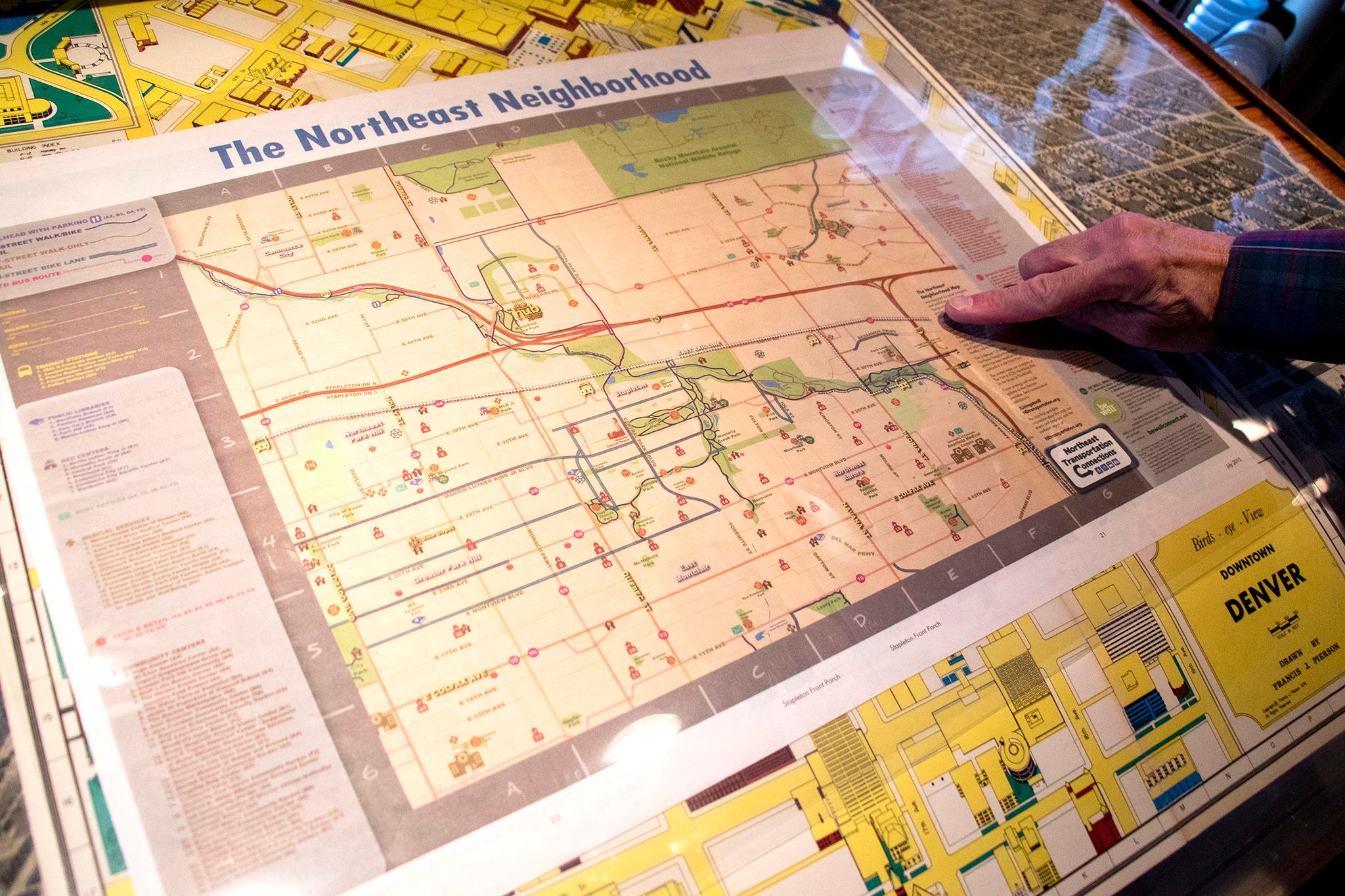

Fast-forward to 2015 and you'll find a "Northeast Neighborhood" map showing future rail line improvements.

"Here, Central Park Boulevard is being put in," Brown said looking at the computer-generated lines.

Other maps in his collection were squarely meant to attract investment.

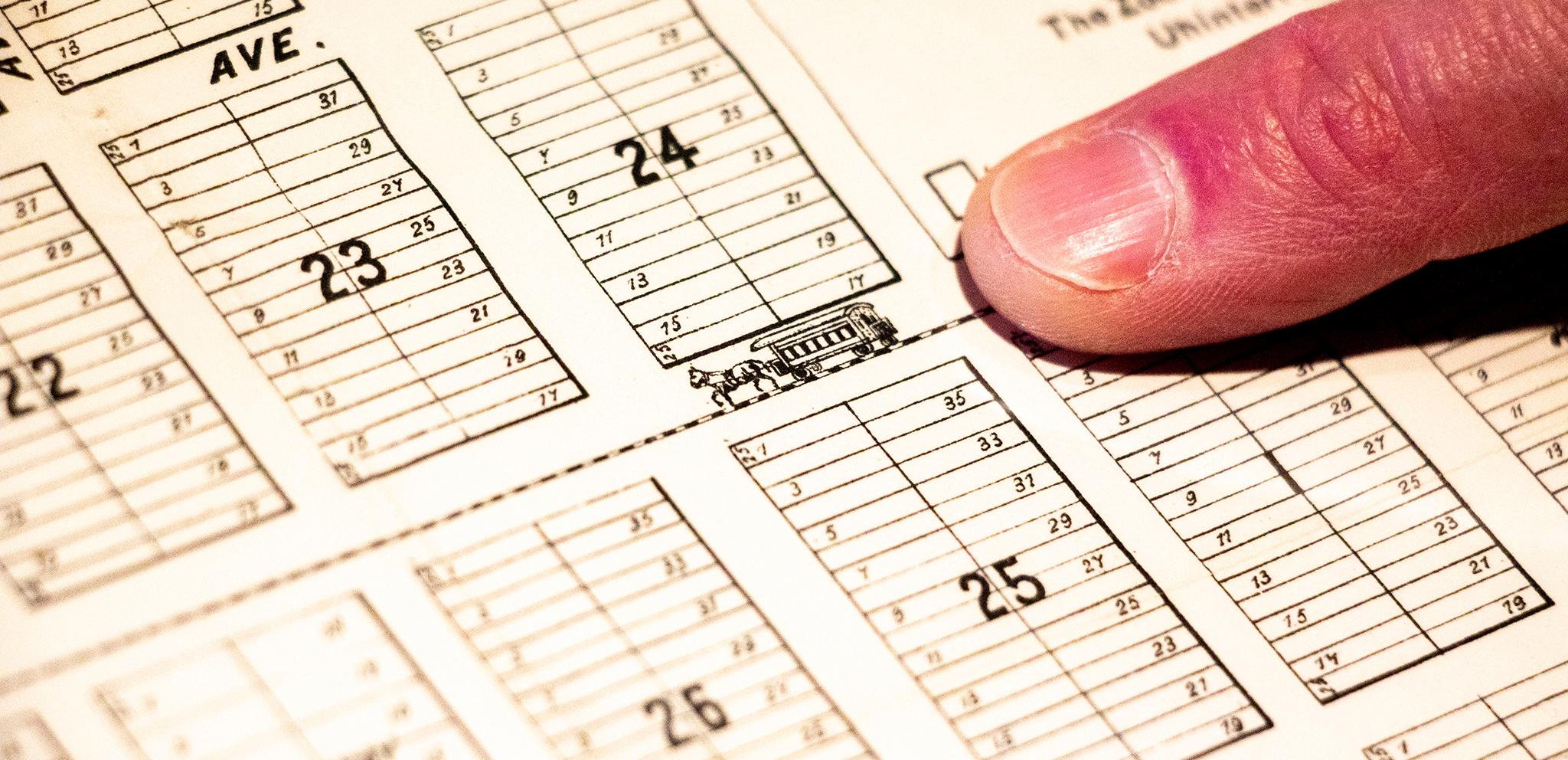

An early map of Montclair, before it was annexed into the city, shows rows of future homes surrounding Colfax Avenue, adorned with a teeny horse-drawn streetcar.

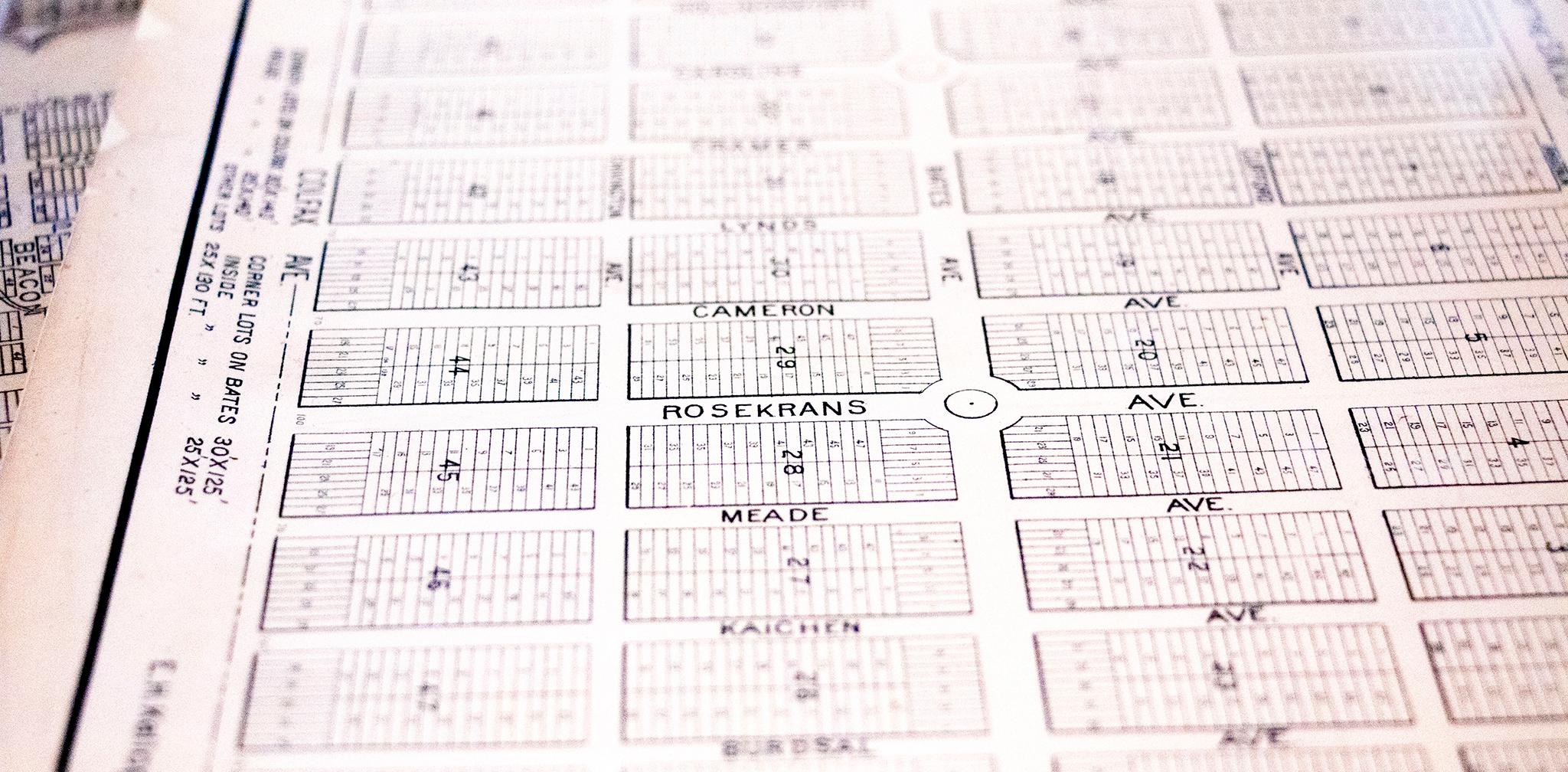

Another neighborhood layout of "Downington," which is now part of South Park Hill, featured street names like "Cameron" and "Roskerans," which no longer exist.

"The developer would pick all his favorite relatives or favorite hobbies or whatever," Brown said, as parcels were put up for sale.

"All these streets are gonna get renamed," he added. "It didn't work with what the city wanted."

Another modern map was used to sell the idea of a rejuvenated Lower Downtown. It depicts a vibrant urban neighborhood girded by a new ballpark and newly activated Union Station.

"My how this has all changed," Brown said, marveling at the piece, at once informative and artistic and infused with commerce.

We still make maps like these to make sense of our city, for our present selves and for our future historians.

Modern Denver maps may not have captured every resident's imagination, but Brown is certain they will some day. He's drawn to pieces that embrace the aesthetic of their times, like one from the 1970s that shows city landmarks awash in technicolor tones.

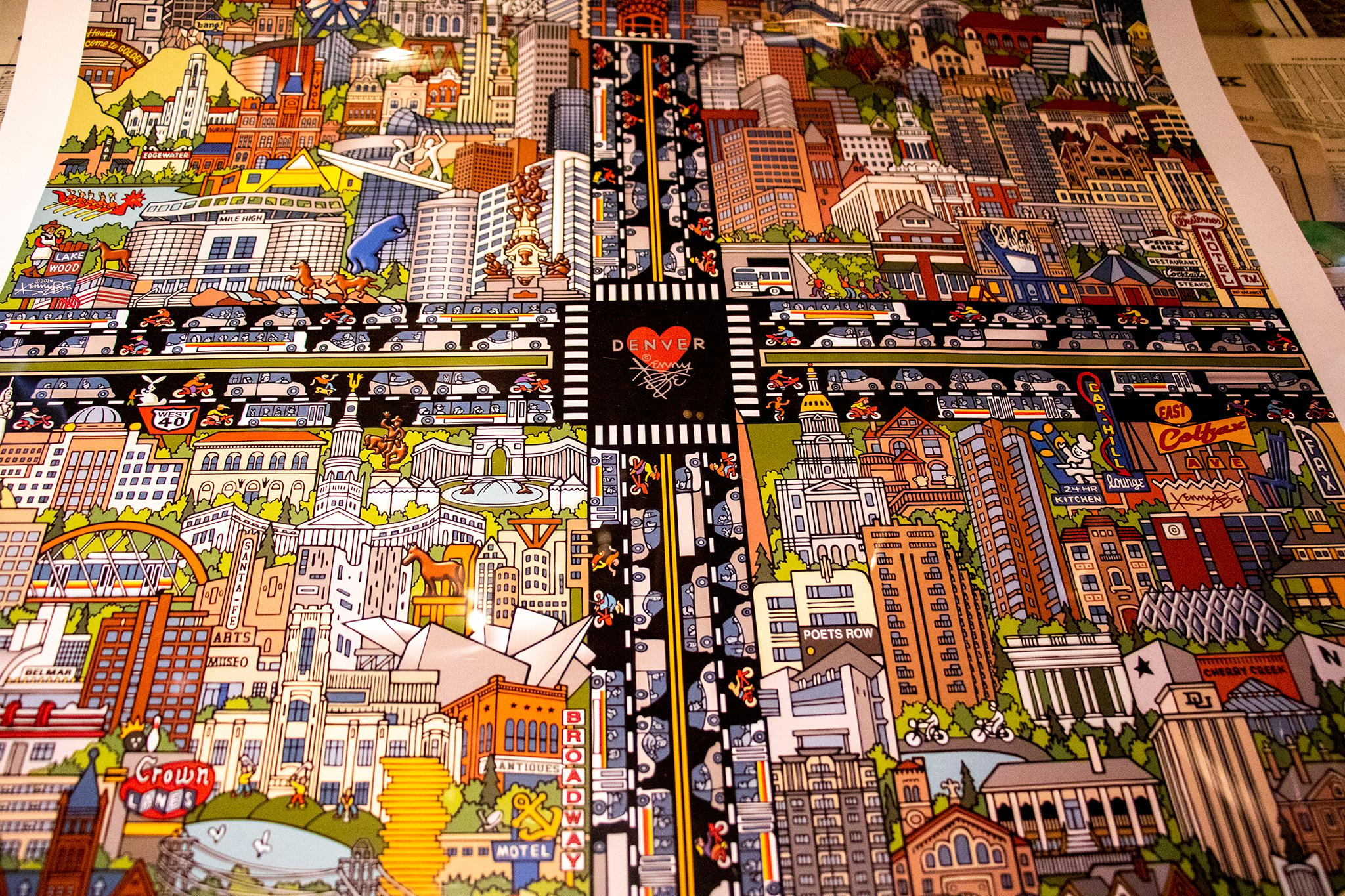

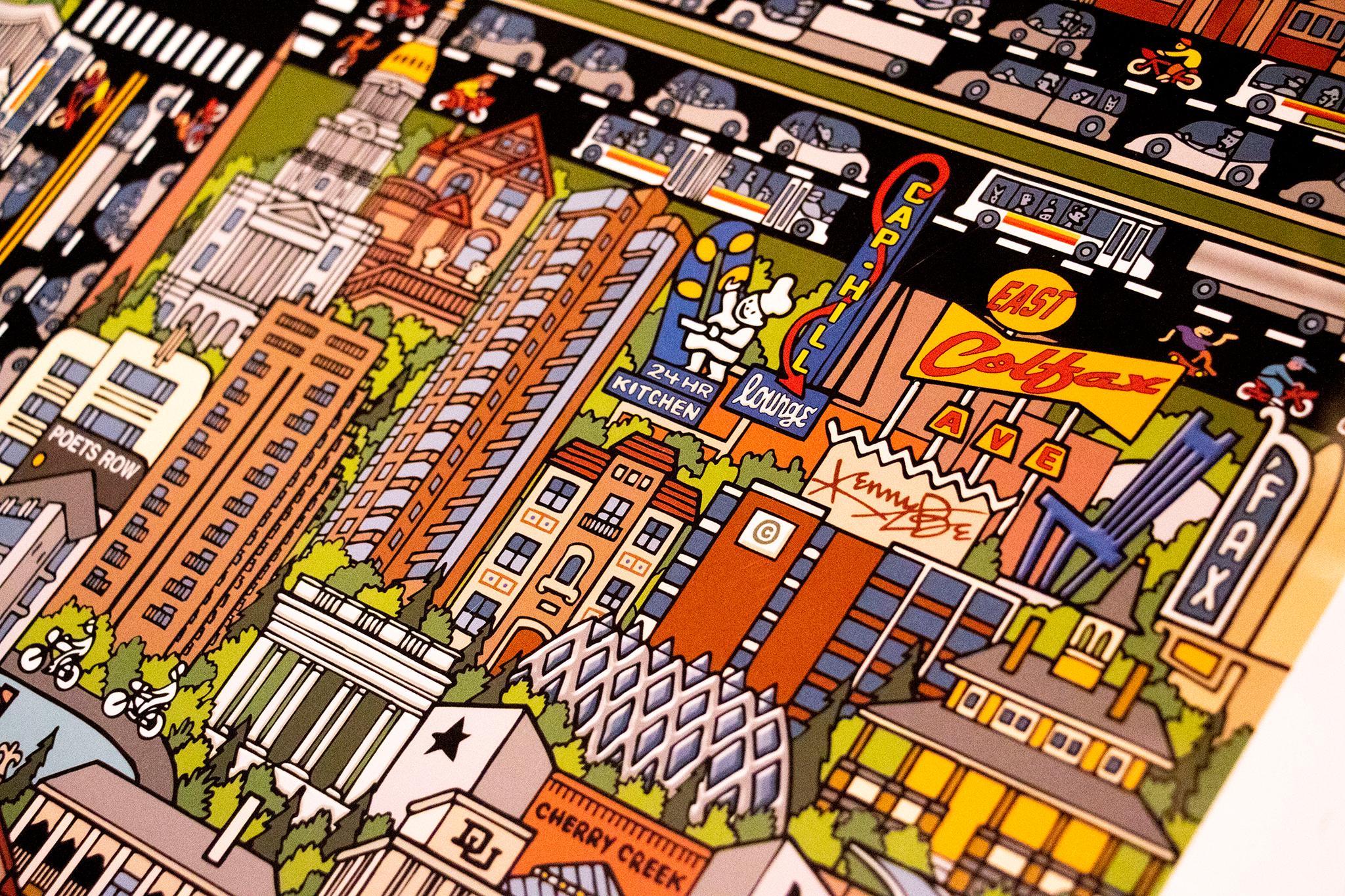

Another, by longtime local artist Kenny Be, shows important neighborhood features radiating out from Colfax and Broadway, which has a heart and his signature emblazoned inside the intersection. The blue bear, DIA's blue demon horse, the dancing aliens, Pete's Kitchen, a dragon boat and the Gothic Theatre are all present in his vision.

And his contemporary collecting is not limited to the artistic. He pulled a 2017 bike map out of a box before he ended his tour.

For Brown, collecting is about archiving our collective understanding of our city. He's sure city librarians and historians will want it all sometime down the line.

"I know what's going to be hot," he said, closing up his map room. "I have more time than the librarians to figure out what's going to be good and go get it."