It's eight in the morning on a Tuesday and because working parents have so much time on their hands, they're logged into a digital waiting room, biting their nails and wondering if they'll get one of the limited number of spots available.

This is not Bruce Springsteen playing Mission Ballroom. This is summer camp registration in Denver.

"I was in tears and I was crying, which is ridiculous. Like, parents shouldn't be crying because they are having trouble getting summer camp for their kids," said Abby Coven, a mother of two who was recalling a glitchy website while attempting to sign up her kids for YMCA day camp one winter. "But it's definitely high stakes."

Just thinking about this is stressful: One of her kids had made the cut, but the other was destined to spend the summer attached to his mom's hip or being shuttled across town to another camp. Coven watched her screen as session after session filled up. Luckily for her, she spoke with a human at the Y who ensured that both of her kids were registered at the same camp for the same session.

Crisis averted. Panic attack maybe not averted.

This is the reality for working moms and dads in a growing city with about 140,000 children and not enough summer camp slots to meet demand.

"There's a little bit of a gap in terms of how fast Denver's grown and the lack of camp programs in the summertime," said Courtney Swanson, camp coordinator for the Denver Zoo, which runs one of the city's more popular camps. "I think that adds the competitive aspect of all the camps in general because there is such a need for summer camp programming. Parents need childcare for their kids and there's just not as many camp programs in the area to fill that need."

The zoo opened registration -- for holders of a $65/year membership -- to its Summer Safari camps on Tuesday at 8 a.m. Three hours later, the slots were about 70 percent full (including kids from families who need financial help; they got first dibs earlier this month). Registration for the general public opens Wednesday.

Parents face more moving parts than a clock.

Cost. Work hours. Summer travel. Price. Transportation. Will both the kids be covered? Will my kid be able to join her friends? Finally: Will she be able to learn about dinosaurs?! It's quite a juggling act.

Some parents must find a place for their child with special needs, adding even more stressors. Stephanie Prince Alexander's daughter has Type 1 diabetes, a disease that requires someone to monitor her 5-year-old daughter's blood sugar and treat her with insulin.

Alexander had no trouble getting her daughter into Denver Public Schools' relatively affordable Discovery Link camp. But she's dreading the idea of ensuring that a trained staffer is there every day.

"I have to go and kind of do my due diligence to figure out who I need to talk to -- who will essentially be in charge of my child's life," she told Denverite. "I think that finding summer camp care for kids is a really intense process for parents. I just think that people don't often think about when you have a special needs child, how much more intense that gets. I can't just sign my kid up for a camp and say, 'See ya.'"

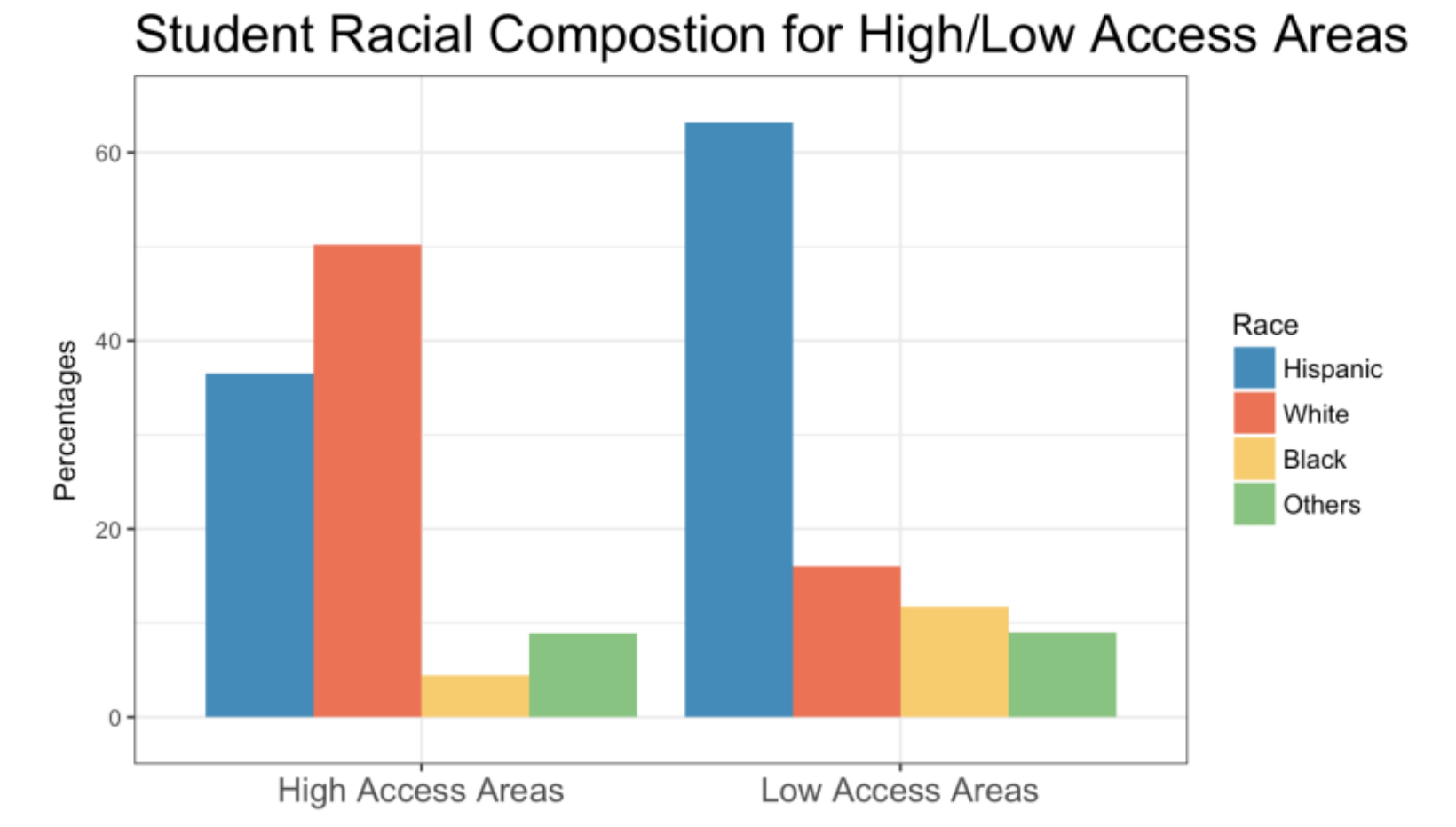

Children with low access to summer camps and classes are more likely to be people of color and low-income. White children with wealthier families tend to have more access. But tools are being developed to change that.

That's according to a study by the Center on Reinventing Public Education, which advocates for more and better ways to educate students outside of the classroom.

"Our early research shows that there are certainly areas of Denver that have not enough supply for the amount of demand," said Jessica Fuller of ReSchool Colorado, which partnered on the research. "There's more kids than there are providers that we know about, especially in the northeast part of Denver and the southwest part of Denver, which is where a lot of our black and brown communities and low-income families are at. But I think that it's more nuanced than that."

For example, different families might have different norms around sending kids to camp. Denver Parks and Recreation camps in areas where Latinx families are most populous, on Denver's west side, have a lower registration rate than other camps, said Jeneanne Ford, a senior recreation supervisor with Parks and Rec.

Most camps reserve space for low-income families and offer scholarships, including the super-popular ones at the zoo and the museum. The city is working on an online "one-stop-shop" for people of all backgrounds and incomes to use for summer camp registration, Ford said. It will launch sometime in February at the earliest.

But at least one online tool already exists: Blueprint4Summer Colorado. Parents can browse the site by interest -- nature, dance, drama, sports -- and find out costs and whether scholarships are available. ReSchool and the Clark Fox Family Foundation developed the site over a couple of years. The site aims to help everyone, but low-income families and families of color in metro Denver especially, said Fuller.

"Obviously our lens on this site is equity," ReSchool's Fuller said. "We're certainly targeting populations that are in the black and Brown community and, ZIP codes where there's more low-income households and things like that."

High demand and relatively low supply can lead to desperate parents doing desperate things.

The zoo camp can hold about 2,300 campers per summer. The Denver Museum of Nature and Science, another particularly popular camp provider, can hold 2,142. City-run camps by Denver Parks and Recreation, which are far less expensive, have 580 slots per summer.

Some parents attempt to "maneuver" the system, said the zoo's Swanson. The camp's customer relations team deals with most complaints, but some get elevated to her. She empathizes with their frustration, she said, but there's little anyone can do when there's no room left, except wait and hope someone bails.

Cutthroat registration happens at more camps than the zoo. Denver's Museum of Nature and Science randomizes its waiting list the same way theaters randomize waiting lists for "Hamilton" tickets, said David Allison, manager of experiences and partnerships for the museum, whose camps are particularly competitive. But schemers will scheme.

"We always try to keep our process as fair and above board as possible," Allison said. "But I think there are loopholes in any system and we have had experiences of folks trying to test those loopholes."

Allison said he can't share what those loopholes are. That... would be anarchy.