Early in the 20th century, adult education pioneer Emily Griffith offered free soup at her Denver school to ensure hunger did not keep students from succeeding.

Early in the 21st century, the school Griffith founded still serves people who see education as a way to escape poverty. And some of those students are going hungry.

Culinary arts students at Emily Griffith Technical College's main campus celebrated what would have been the 152nd birthday of their founder on Monday by serving free soup to anyone who asked. In all, 125 bowls of vegetarian or beef and barley soup were ladled out on Monday, which also kicked off a food drive to help stock the school pantry where students can grab a quick lunch any day.

"Helping a student not be hungry is just a meaningful way to support students," said Krista Kliebenstein, who coordinates the Student Success Center where Emily Griffith students can get tutoring and other help.

Donations to the food drive, which ends Feb. 28, can be dropped off weekdays between 8 a.m. and 6 p.m. at Emily's Café, the student-staffed restaurant on the ground floor of the high rise school at 1860 Lincoln Street, or on the sixth floor of the building. Emily's Café was also the site of Monday's soup give-away.

Financial donations to the food drive can be made by contacting Shannon Geis at the school at [email protected]. Kliebenstein said the Denver Public Schools affiliated institution school was mainly seeking food donations such as instant noodles, ready-to-heat soups, fruit cups and granola bars that students can eat during busy days.

Many Griffith students are in class from 7:30 a.m. to 4 p.m. four days a week with 30 minutes for lunch. They are working to quickly gain skills and start jobs. A certified nursing assistant certificate, for example, can be earned in five weeks, Kliebenstein said.

In addition to culinary arts and health sciences, Emily Griffith students can study in such areas as creative arts and design, administration and trades and industry. The school has apprenticeship programs at sites across Colorado, including Colorado Springs and Pueblo. Emily Griffith's Denver facilities include a College of Trades & Industry at 1205 Osage Street and a video production and editing program at 200 E. 9th Avenue.

Kliebenstein said some 40 students every day get something to eat from the pantry, a metal cabinet on the fifth floor of the downtown building that also houses the DPS Board of Education, Downtown Denver Expeditionary School and Emily Griffith High School.

Word of the pantry is spread among students, who can drop in as needed. The pantry started four years ago. Initially, teachers and administrators stocked the cabinet themselves, but the need soon outstripped their ability. In addition to donations from the public, the school has relied on the Emily Griffith Foundation, which raises money for student scholarships and other needs, for help with the pantry.

Kliebenstein said instructors who spend hours every day with students see when hunger keeps them from focusing or from getting to class at all.

"We're very small. But we're mighty," Kliebenstein said. "We really try to collaborate, to work together to provide resources for the students."

Hunger among students at post-secondary institutions has been a growing concern in Denver and across the country.

Each of the three schools on the Auraria campus -- the Community College of Denver, Metropolitan State University of Denver and the University of Colorado Denver -- has its own food pantry. Four in 10 students at the Auraria schools worry about running out of food before being able to afford more, according to a survey last year by the Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice, a think tank at Temple University. The Hope Center has conducted such surveys at schools across the country and found similar conditions.

Denver's Regis University and the University of Denver also each have a pantry for students.

Kliebenstein, who has worked at Auraria and at the Community College of Aurora, said she was initially startled when she read that a national study had found 48 percent of students had been uncertain they would be able to eat in the previous month.

But "when I sit and think about the students I work with, it's not surprising," she said.

Earlier Monday, she said, she had been helping a student find emergency housing.

Housing "affordability is just a real challenge for not only our students, but everyone trying to make it in Denver," she said.

She said she expected problems stemming from poverty to grow as Emily Griffith saw more students who are from immigrant or refugee families or the first in their families to pursue education beyond high school.

"When you provide accessibility, you also become aware of what those students living below the poverty line are dealing with," Kliebenstein said.

The founder of the school where Kliebenstein works left school herself after the eighth grade to help her own impoverished family. The Griffiths moved from Cincinnati, Ohio, where Griffith was born, in search of work, first struggling to farm in Nebraska and then coming to Denver. Griffith, largely self-educated, taught school in Five Points. She also tutored her students' parents, seeing that lack of education was holding families back.

When she opened her tuition-free Opportunity School for adults in 1916, Griffith hung a sign over the entrance: "For All Those Who Wish to Learn." Kliebenstein said the motto still sums up the school's philosophy.

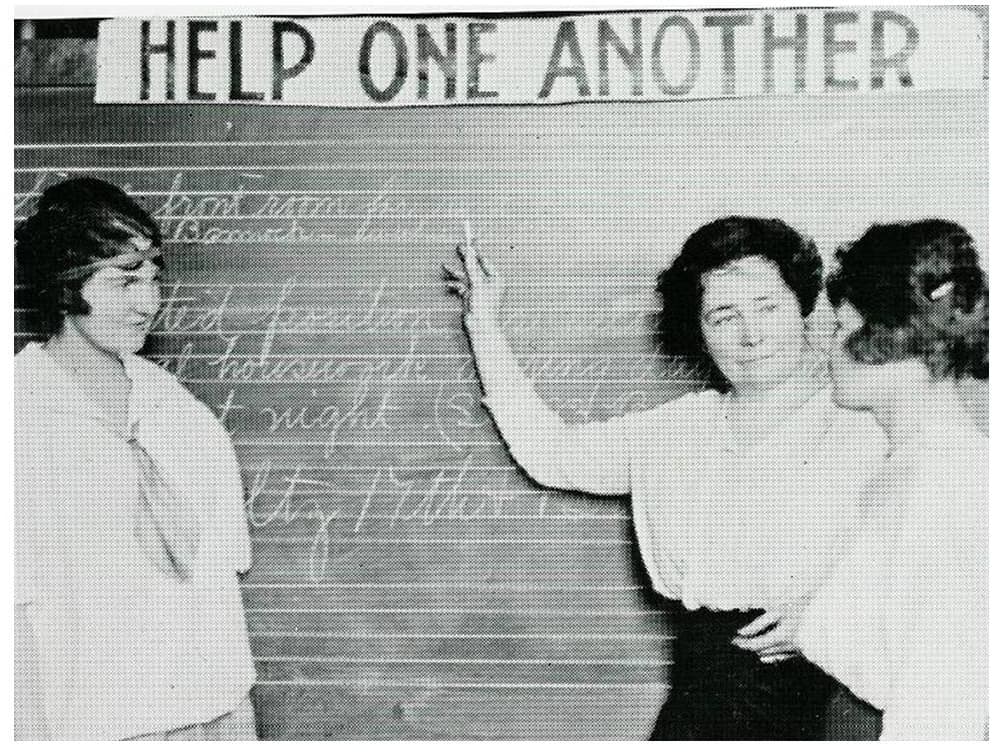

According to school history, Griffith and her sister, Florence, began providing soup after a student fainted during an evening class. A message was written on a blackboard: "A bowl of soup is served in the basement from 5:30-7:30. Free. This saves you time."

A year after Griffith retired as principal in 1933, the school was renamed Emily Griffith Opportunity School and later, to reflect its expanded mission, Emily Griffith Technical College.

After retirement, Emily Griffith and Florence Griffith lived in a cabin in Pinecliffe near Nederland built by a friend Fred Lundy, a retired teacher from the Opportunity School. The sisters were found shot dead in their cabin in 1947. Their murders remain unsolved, though police suspected Lundy, who committed suicide after the deaths.