Jorge Ávila is a religious man, but he didn't expect to spend this much time in a church-slash-synagogue.

Ávila, a 31-year-old undocumented Denverite who grew up in the city's public school system after emigrating from Mexico in 2000, has been living with his family in the basement of Park Hill United Methodist Church and Temple Micah since December 10. He's waiting out federal immigration authorities who he believes will deport him if a decision by an immigration court doesn't go his way.

"I believe in God," Ávila told Denverite on Tuesday from his "apartment" -- a windowless but homey basement with a blue sectional couch and a kitchenette. "So I believe that everything will result in a good way. So basically God is giving me the strength to be here with my family."

Ávila lives in pseudo-hiding with his wife, Alejandra, their three young daughters and their 3-year-old son. U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement tends to leave "sensitive locations" like churches alone, according to the agency's official stance and recent local history. Sanctuary4All, which supports and advocates for immigrants in Colorado, is helping the family during its stay, which could last weeks, months or even years.

Ávila had an appointment with an immigration official late last year "that was likely to lead to his immediate deportation," a press release from Sanctuary4All stated. "Rather than attend that meeting, Jorge chose to take refuge" at the church, advocates said.

At least three people are known to be in sanctuary throughout Colorado. But that number only represents public cases; some would prefer not to go public with their immigration situation.

"The reason is basically because we want to take this as a message for other people having the same problem," Ávila said of his decision to go public. "And there are ways to work on their cases and not just go back to Mexico or other countries. I do it so they can keep fighting for their cases."

Ávila's journey to his temporary subterranean home started a decade ago. If it had started later, he may have avoided ICE's radar.

About 10 years ago, he racked up 10 traffic infractions while driving, including driving without a license, court records state. His advocates say those tickets stemmed from his work as a delivery driver, a job that was necessary to support his young family, and blame them for attracting ICE's attention. A spokesperson for ICE did not confirm how the agency caught wind of Ávila, saying she was waiting for permission to divulge more information Tuesday.

Denver's city government probably would not share information on traffic tickets with federal officials today, said Ryan Luby, spokesman for the Denver City Attorney's Office. He was not commenting on Ávila's case specifically -- Luby was referring to a law passed by the city council in 2017 that limited what city employees could share with ICE. More recently, the Trump administration sued Denver over immigration records.

"There would have been much more information shared more freely back then," Luby said. "If ICE had come to the city back in 2010 and said, 'Hey, do you have any information whatsoever,' there was a far greater likelihood that we would share that information with little hesitation."

Federal court records paint a picture of a troubled kid who was once caught with a weapon in school -- a charge that was dismissed in 2005 -- and who had gang affiliations as a child.

"Regarding gang affiliation, I wanted to let you know that I did belong to a gang when I was under the age -- a minor, but after I got married, all this stopped, and I have not maintained contact or belong to any gang anymore," Ávila told a judge, according to court documents.

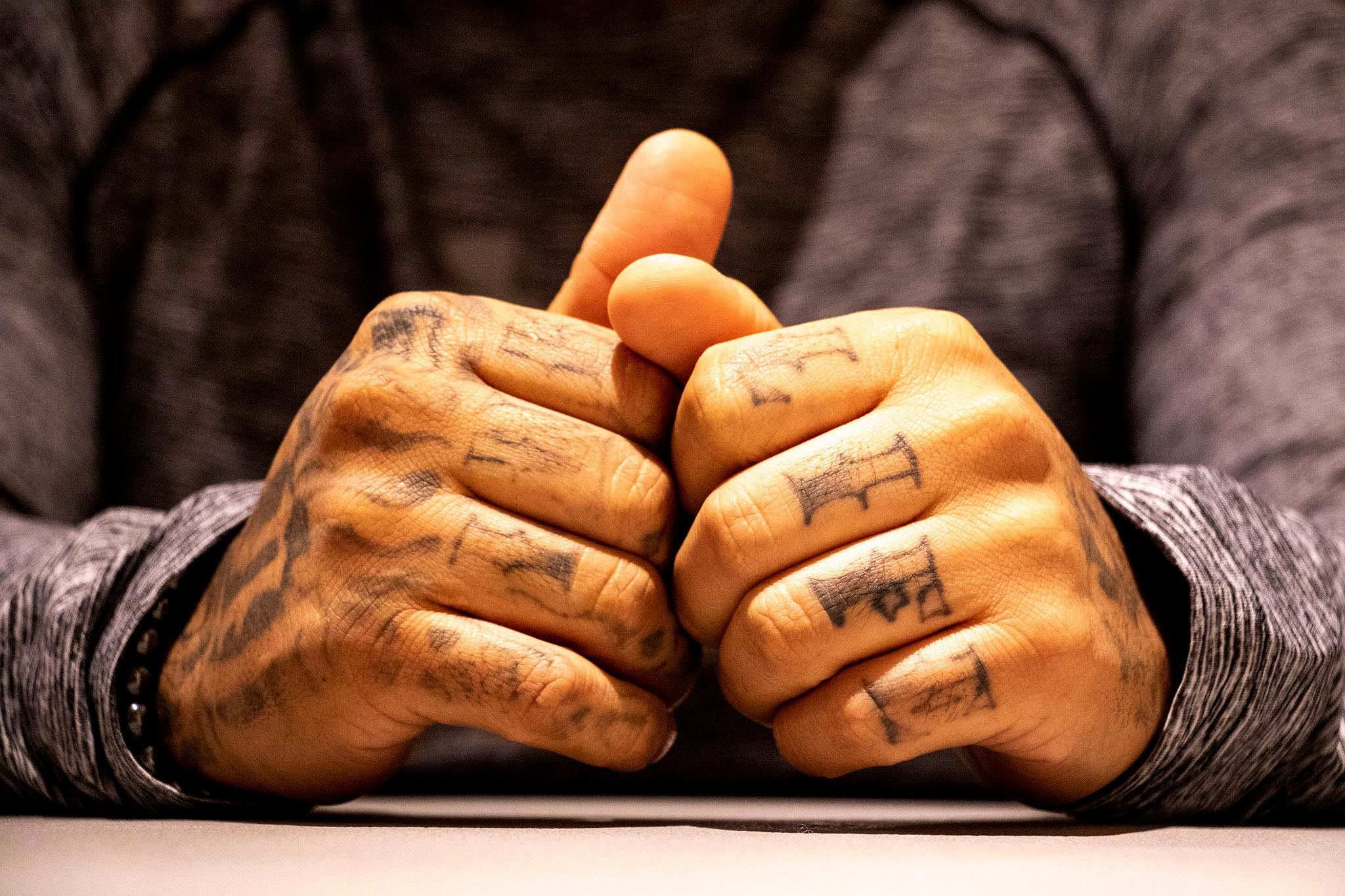

Still, it could be years before he's free to live his life in public, the longtime Denver resident with a fresh Broncos flat-brim and tattoos giving equal play to Mexico and the Mile High City told Denverite.

"But it doesn't matter how long I stay here," he said. "I got to say I'm doing this for my kids and if we have to stay years, months, weeks. It doesn't matter."