Sandy Pierce and Kari Bell can see Red Rocks, and the Rocky Mountains beyond it, from their home, a modern three-story building perched on a hill on Denver's southern edge.

When they bought the place in 2015, their real estate agent used the view as a selling point, telling them it would always be there. But the vista from the living room won't be uninterrupted much longer, the wife and wife say. A home-builder will answer Denver's constant call for housing with a five-story apartment building that will soon rise a few blocks away.

"Having the view sort of opens our world," Pierce said while staring west toward the Rockies. "Now it's been taken away without any kind of recourse."

There's no recourse because views don't belong to private citizens, said Elizabeth Weigle, a senior city planner with Denver Community Planning and Development.

"If you happen to live in an area where, from your house or from the balcony of your tall building, you have a big view of the mountains, that makes you lucky," Weigle said. "But that's not something that the city -- we don't protect private views."

Denver does protect views from public places, through a designation encoded in city law. The protected views are called -- say it with me, nerds -- view planes. Essentially, they prevent development from blocking vistas from places where people gather, mostly parks. The goal is to safeguard places "people will always want to be and have access to," Weigle said.

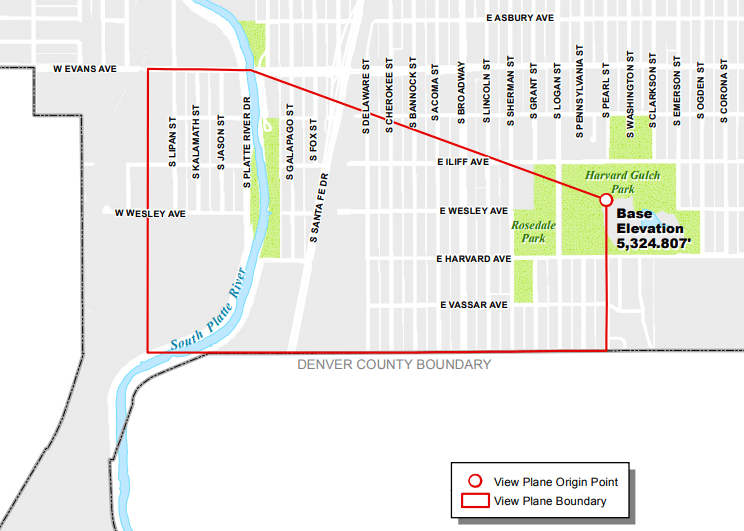

Denver has 14 view planes, named mostly for the places with protected views, like Old City Hall and Cheesman Park. The State Home view plane is down the street from Pierce's and Bell's house, and it protects the panorama from Harvard Gulch Park. The views from Rosedale Park and City of Kunming Park are included in State Home as well (Pro tip: go to Kunming Park for a mean sunset).

The loss of a vista for some will mean gains for others.

The apartment building Flywheel Capital plans to build at the intersection of South Broadway and Yale Avenue, three blocks away from Pierce and Bell's Home, will have between 80 and 85 homes. Some tenants will have exceptional views of the mountains. The development, OK'd by the Denver City Council last month, will supplant a couple of sprawly parking lots, a tire shop and a used-car dealership.

The building will offer everything from studios to three-bedrooms, said Matt Godley with Flywheel. Eight or 10 units will supposedly be income-restricted -- affordable to a household of two making about $59,000. (While the developer has signed a non-binding agreement to implement affordable housing with Overland Park neighbors, it has yet to sign a binding contract with the city, citing delays at the federal level with affordable housing incentives.)

Ground-level shops and restaurants will create a lively, walkable atmosphere, Godley said. He thinks the project will make a somewhat rundown area more viable for local businesses.

"We are committed to this neighborhood, and we'd like to see this project come to fruition so that we can continue to enhance the livelihood and provide amenities to the residents that they deserve on this section of South Broadway," Godley said.

The Overland Park Neighborhood Association endorsed Godley's project after working with the developer. Several people spoke against the project at a city council meeting last month when the developer was seeking permission to build five stories where only three stories were previously allowed. Most of them, including Pierce and Bell, live in Rosedale, across Broadway to the east.

After learning about the project and view planes, Pierce and Bell were under the impression that the State Home view plane would protect "their" view.

After all, their house falls within the view plane boundary. But, confusingly, that doesn't mean their precious panorama is safe. Only views from the plane's origin point (the white dot on the above diagram) are protected. Developers who propose buildings within the red boundary must prove that their project doesn't impede the view from Harvard Gulch Park. Any private views preserved in the process are incidental, a spokesperson from Denver's planning department said.

"You feel like that was a tool meant to stop this exact thing from happening," Bell told Denverite. "I feel, in that respect, that you're violated."

Godley's project is seventy feet high, six feet below what's allowed in the view plane, city planners said.

The couple fought against the project at the council meeting last month. They and others from the Rosedale neighborhood who fought the project cited views, but also fears about more traffic and fewer street parking spots. Some tried to equate more homes with more crime.

In the end, city council approved the project.

"As someone who grew up in Denver in a single-family home community and live in Denver in a single-family home community, I think that some of the ways that we can reduce our collective impact on the planet and combat climate change while also protecting our single-family homes is to find places where density is appropriate and make sure that we are supporting density where it's appropriate," said city council President Jolon Clark, who reps the Overland Park neighborhood.

And the opposition couldn't stand up to the law. City council members are supposed to vote on rezonings based on whether they align with previously adopted development plans, the zoning code states.

Pierce and Bell will still be able to see the mountains unimpeded from their upper floors and balcony. But they consider this apartment building the first of many dominoes to fall, and it's making them rethink where they want to live.

"We never thought we would, but it has occurred to us now, which is a big deal," Pierce said.