Earlier in the week, the New York Times reported that large U.S. cities saw air pollution "plummet" as they locked down to protect residents from the novel coronavirus.

Does that apply to other cities? Frank Flocke, a scientist with the National Center for Atmospheric Research, said we should hold our collective horses.

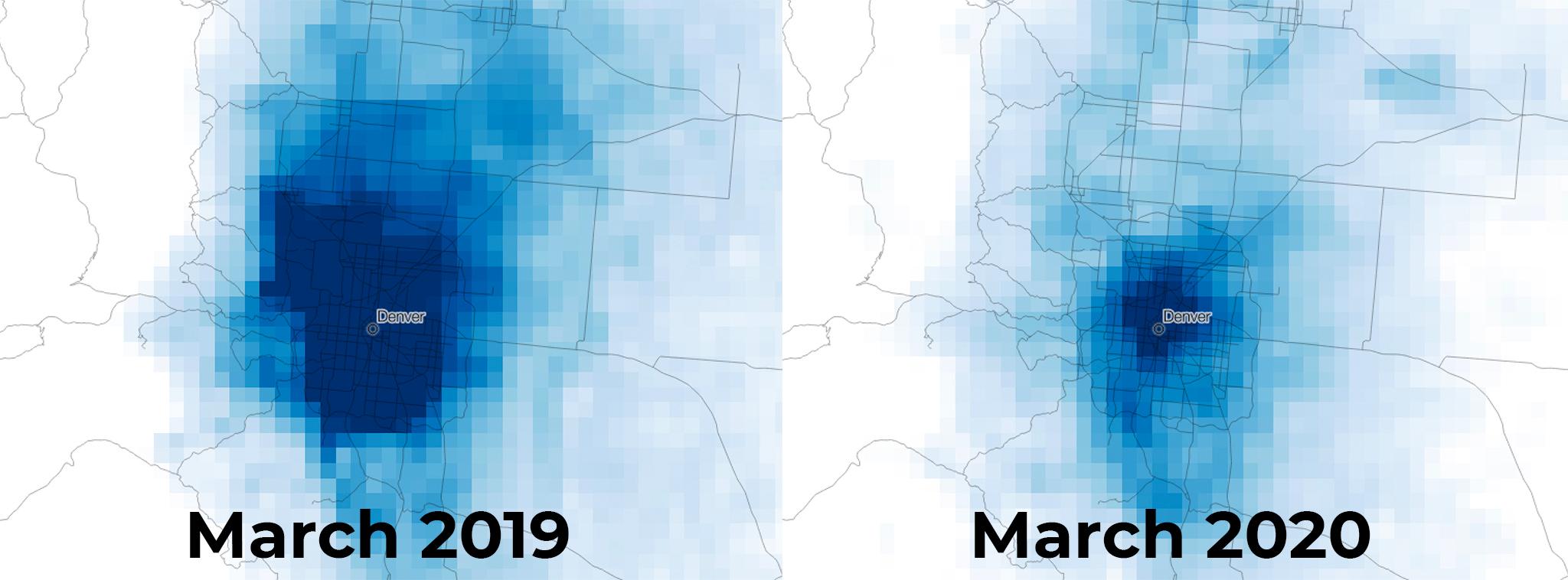

The data cited by the Times comes from satellites that measure nitrogen dioxide emissions (NO2), and their story showed maps of pollution between March 2019 and 2020. Flocke pointed Denverite to a missive from Europe's Atmospheric Monitoring Service that called the mapping, compiled by Descartes Labs, "flawed." In short, the Service complained that weather conditions - particularly cloud cover - was vastly different between the two years and the maps published by the Times didn't take those changes into account.

"While we expect to identify reduction trends after some weeks of lockdown, some marked trends being identified in areas where measures have been taken only recently are questionable," the rebuttal reads.

Now, this may be inside baseball to anyone who's not a scientist. There are atmospheric shifts happening as a result of shelter in place orders and social distancing. But, Flocke stressed, this stuff is magnificently complicated and anyone who wants a quick and dirty answer needs to accept that one may not exist.

We tried to find one anyway.

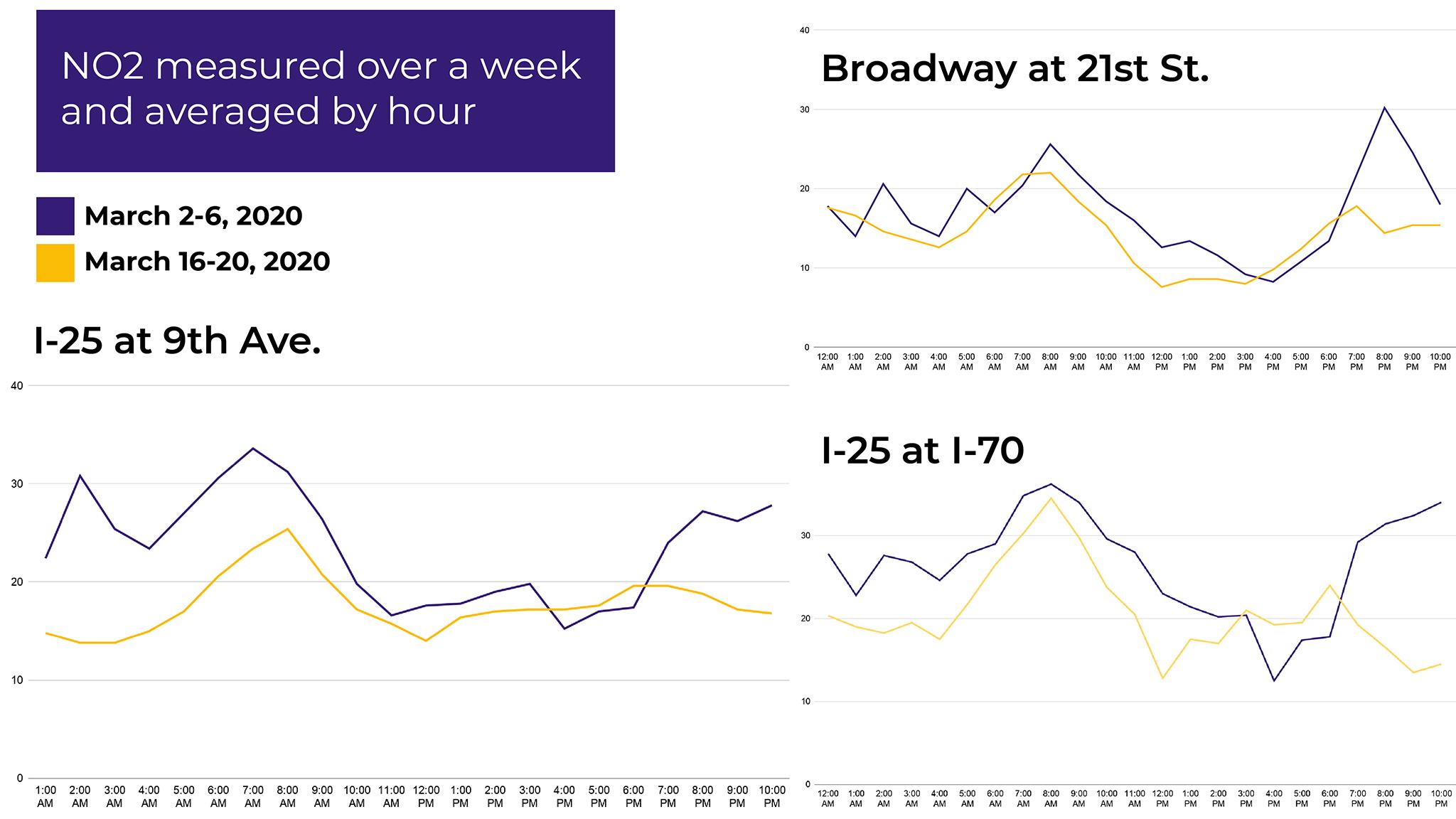

The EPA operates a number of air quality sensors around the city, and the state's health department keeps that data on their website for just anyone to look at. We grabbed hourly measurements for the first week of March 2020 and compared them with measurements from March 16-20, 2020, the first week of real social distancing in the city.

We took averages of hourly data for each of those ten days and compared them - so the pollution we report in the 8 a.m. slot combines all of the week's 8 a.m. measurements into one average. You can see peaks for morning rush hour in both weeks' data, and that's what we'll focus on here.

Below are graphs of three EPA sensors that test for NO2. Two of them are right next to I-25: one is by 9th Avenue and the other is just north of I-70. The third is that cute little air monitoring station on Broadway by 21st Street.

The first week of March might show us a typical morning rush hour for the city. Near the highway, NO2 peaks just above 30 parts per billion at 7 or 8 a.m. It's a little lower in the heart of the city.

The trends for the week of social distancing shows morning NO2 growth happening, too, but it stops short of the highs we saw two weeks before. The I-25 and 9th Avenue sensor suggests NO2 peaks dropped about a quarter between the two weeks.

Flocke was interested in the I-25 sensors and said they're "pretty telling." One reason for his confidence is how close those monitors are to the highway. Air pollution can be extremely location-specific, and there's no telling how many sources of emissions contribute to a given measurement.

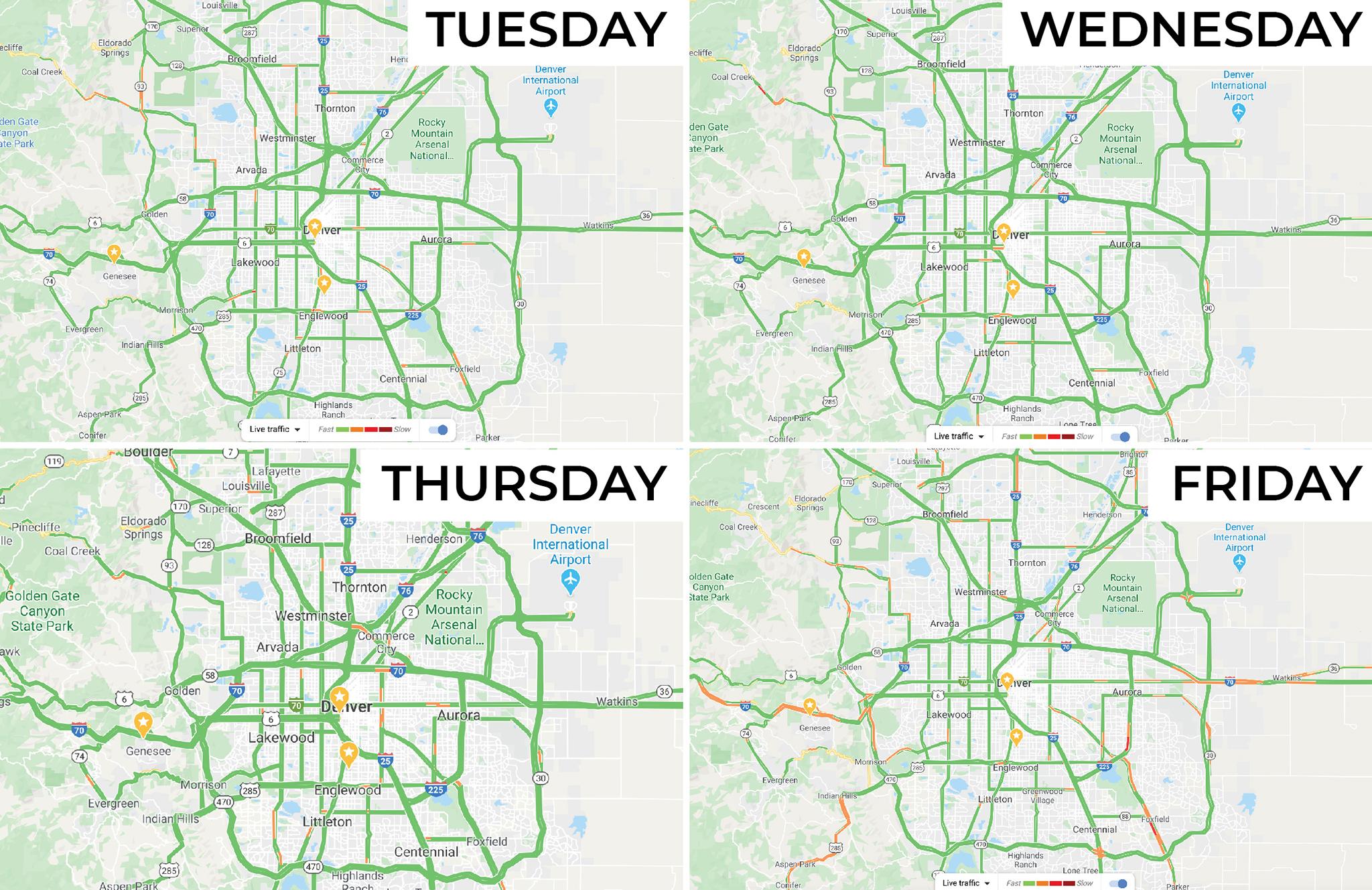

Based on Google Maps traffic data we've collected over the last weeks, we know the usual backups during morning rush hour have all but disappeared. The fact that the I-25 sensors are so close to the highway means we can say with some degree of certainty that a change has to do with how many cars are on the road.

We also used the EPA data to look at ozone and particulate matter, but Flocke said the trends we found were too muddy to use. All air pollution, NO2 included, is subject to wind patterns and weather. Ozone is even more complicated, because certain chemicals in the air transform into ozone when they react with sunlight. If the wind blows in a different direction between two days of measurement, or if the sun peeks out a little more, a sensor could record vastly different levels of a pollutant.

Even still, Flocke said the EPA sensors wouldn't satisfy a (capital-S) Scientific study. They "really are scientifically insufficient," mainly because the scope of what they measure is limited to one point.

This is a moment for science, but we'll have to wait for conclusive results.

Air traffic virtually stopped after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, and Flocke said that became a moment like we have today: existential circumstances changed behavior and created a natural experiment for scientists to study.

Months after the World Trade Towers fell, scientists began to analyze how the atmosphere was impacted by the absence of planes in the sky. One study published in Nature said, for instance, that average daily temperatures were higher in the three days when air travel was completely stopped, possibly because there were no contrails from planes over the country.

Flocke would like to see researchers take measurements from planes above the city to truly capitalize on lower NO2 emissions during this era of COVID-19. Unfortunately, he said, it's not allowed right now under shelter-in-place rules. He also said the kind of satellite analysis that the Times wrote about will become useful, researchers just need to process the unrefined data (like the maps that have been floating around the internet) and account for changes in cloud cover throughout the entire atmosphere.

Dr. Jill Baron, a U.S. Geological Survey researcher based at CSU, has been collecting samples from Rocky Mountain National Park's Loch Vale since the 80s - it's one of the longest-running ecosystem studies in a national park. She also said she expects to see this moment impact her data, though her team is not allowed to trek up to the Loch to collect samples at the moment.

"Sadly, very sadly, we are not collecting samples. The park is closed and gated, we are prohibited from traveling, and we are losing important information," she said.

But despite the difficulty in getting work done, Flocke said he's confident some good science will come out of these odd weeks of "work from home."

He specializes in modeling ozone emissions, and some of his past work suggests that a third of the ozone produced between south Denver and Fort Collins comes from cars on the road. He's looking forward to see how he or his colleagues might understand more about our impact on the air as a result of so few drivers out right now. He'd just like to see a lot more nuance if the media reports on that work.

"There's a lot of people that are cranking out stuff that is not really well thought out," he said. "That's OK. It gets people to read the paper."